The Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule

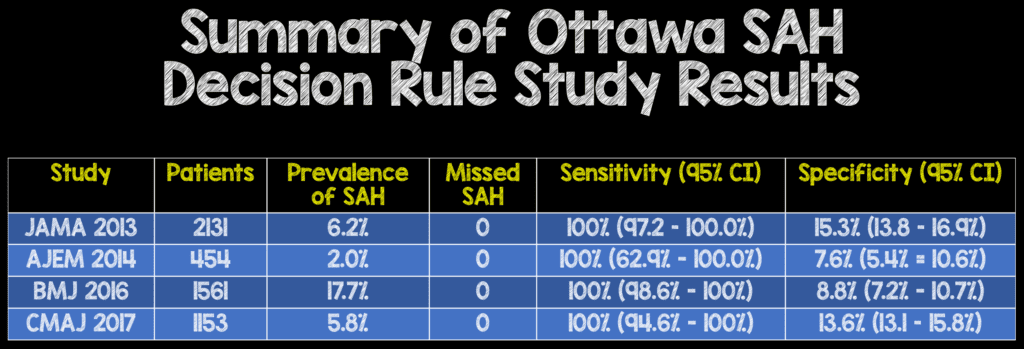

Summary of Sensitivity and Specificity of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

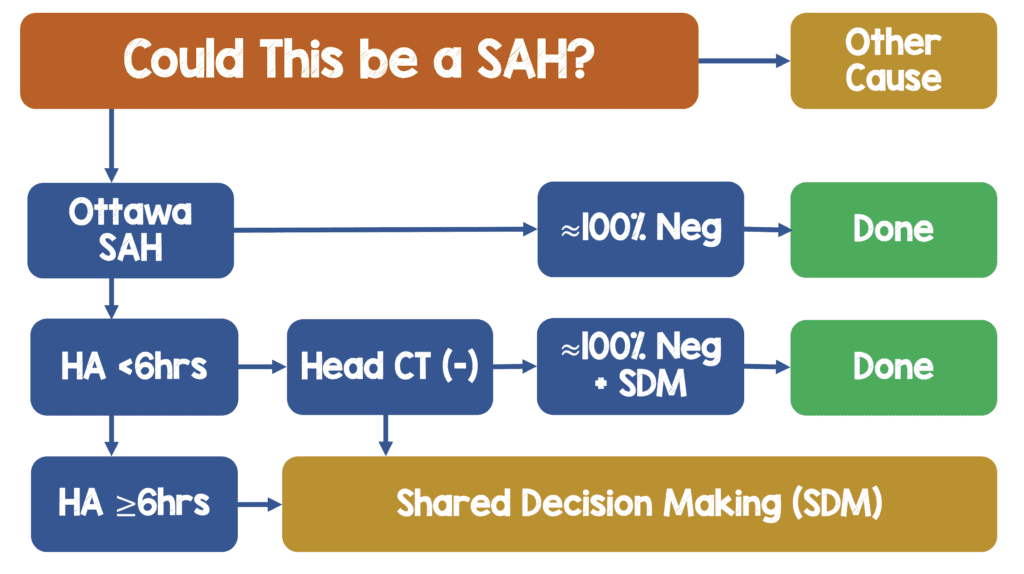

My Workflow of SAH

Clinical Take Home Point:

- The Ottawa SAH Decision Rule is Defined as any of the following as a high-risk patient requiring further workup:

- Age≥40y

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed LOC

- Onset during exertion

- Thunderclap headache (instantly peaking pain)

- Limited neck flexion on exam

- To date the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule holds a 100% sensitivity for ruling out SAH, in >5,000 adult patients, from 4 countries, who are alert, neurologically intact (GCS 15) presenting to the ED with acute non-traumatic headache. It is important to remember that most studies confidence intervals went down to 98% and one small study went as low as 63%, so take the 100% sensitivity with a grain of salt

- Subsequent studies have shown the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule has limited application to a small proportion of patients presenting with acute headache (5 – 25%) which may limit its adoption in general practice.

- Some of the factors in the Ottawa SAH Decision rule are subjective (i.e. headache during exertion, neck pain or stiffness) which may decrease interobserver reliability in other environments

- The specificity of the Ottawa SAH Decision rule (7.6% – 15.3%) is also poor which can lead to more patients needing further workup (head CT and/or LP) who have one or more high risk features. This is a 1-way decision instrument. In other words, a positive decision rule risk factor does NOT mean you would have to pursue SAH. Clinical judgement must be used in determining which patients will require further workup as blanket workups will lead to increased health costs, and potential harm (radiation and invasive procedures) to patients.

References:

- Perry JJ et al. High Risk Clinical Characteristics for Subarachnoid Haemorrhage in Patients with Acute Headache: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2010. PMID: 21030443

- Perry JJ et al. Clinical Decision Rules ot Rule Out Subarachnoid Hemorrhage for Acute Headache. JAMA 2013. PMID: 24065011

- Perry JJ et al. Validation of the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule in Patients with Acute Headache. CMAJ 2017. PMID: 29133539

- Bellolio MF et al. External Validation of the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Clinical Decision rule in Patients with Acute Headache. AJEM 2014. PMID: 25511365

- Chu KH et al. Applying the Ottawa Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Rule on a cohort of emergency Department Patients with Headache. EuJEM 2017. PMID: 29215380

- Kumura A et al. New Clinical Decision rule to Exclude Subarachnoid Haemorrhae for Acute Headache: A Prospective Multicentre Observational Study BMJ 2016. PMID: 27612533

- Ramachandran S et al. Can the Ottawa Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Rule Help Reduce Investigation Rates for Suspected Subarachnoid Haemorrhage? AJEM 2018 PMID: 29776829

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- Natalie May at St. Emlyn’s: JC – Subarachnoid Haemorrhage, Decision Rules, & Overtesting Headaches

- Anand Swaminathan at CORE EM: The Ottawa SAH Decision Instrument

- Ken Milne at The SGEM: SGEM #201 – It’s in the Way That You Use It – Ottawa SAH Tool

Hot off the Press!!!

Paper #1: Syncope vs Near Syncope

Bastani A et al. comparison of 30-Day Serious Adverse Clinical Events for Elderly Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department with Near-Syncope Versus Syncope. Ann Emerg Med 2018. PMID: 30529112

Many providers consider near syncope a milder form of syncope and therefore not as dangerous. The issue is the definition of near syncope is very nebulous and subjective. Paper number 1 was a multicenter prospective cohort study of ≈7,000 patients aged ≥60 years from 11 emergency departments in the US. The primary outcome was a composite outcome of all-cause mortality or serious clinical events at 30 days. Serious clinical events were defined as cardiac arrhythmias, MI, cardiac interventions (pacemaker or defibrillator or PCI), stroke, PE, aortic dissection, SAH, cardiac arrest, hemorrhage, or fall with major injury.

The primary outcome results were syncope and near syncope were the same risk: 18.2% in syncope and 18.4% in near syncope. There was no statistical difference in this outcome. An 18% death and serious clinical event rate at 30 days is a large number, but unfortunately this study doesn’t tell us what to do with these patients: admit vs observation vs discharge. Admission to the hospital does not guarantee that a cause will be found, or outcomes will be improved (i.e. mortality).

Clinical Bottom Line:In patients ≥60 years of age, near syncope portends a similar risk as syncope for death or serious clinical outcomes at 30 days.

Paper #2: PE Prevalence in Syncope

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Emergency Department Patients with Syncope: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med 2019. PMID: 30691921

The PESIT trial which was published in 2016 stated there was a 17.3% rate of PE in syncope patients, BUT many patients were admitted with signs and symptoms concerning for PE (tachycardia, tachypnea, and DVT) and not evaluated prior to admission. Using the results of this study would lead to increased imaging.

Paper number 2 was a prospective multicenter cohort study with 9,000 patients from 17 emergency departments in Canada and the USA. The primary outcome was PE at 30 days.

The major results of this paper showed that PE at 30 days was 0.6%, PE diagnosis at index ED visit 0.5%, and death from PE was 0.04%. This should re-iterate the fact that the PESIT trial was an outlier and investigating for PE when history, signs, or symptoms of PE/DVT are not present, we should not be routinely working these patients up for PE as a cause of syncope

Clinical Bottom Line:PE work up should NOT be a routine part of syncope workup but rather should be undertaken if there is history concerning for, or signs/symptoms concerning for PE/DVT.

Paper #3: Heparin in NSTEMI

Chen, JY et al. Association of Parenteral Anticoagulation Therapy With Outcomes in Chinese Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Intern Med 2018. PMID: 30592483

The 2014 AHA NSTEMI recommendations currently recommend unfractionated heparin (Level B evidence) and enoxaparin (Level A evidence) for patients with a diagnosis of NSTEMI. There have been 6 randomized clinical trials published with ≈2,000 patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI. Pooling the results of these studies showed no benefit in death, MI, or angina symptoms with an increased risk of bleeding. The major caveat is all these studies were published before 1996 when dual anti-platelet medications were not routinely used, and PCI was not as common.

Paper number 3 was a retrospective cohort study of 6,800 patients (60% with NSTEMI and 40% with UA). The study divided patients into patients who received anticoagulation prior to PCI vs patients who received anticoagulation during PCI. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality and major bleeding.

The results of this paper were no difference in in-hospital mortality (parenteral anticoagulation before PCI = 0.3% and no parenteral anticoagulation before PCI = 0.1%) and increased major bleeding (parenteral anticoagulation during PCI = 2.5% and no parenteral anticoagulation before PCI = 1.0%). Parenteral anticoagulation prior to PCI made no difference in mortality, or subsequent MI, but had increased major bleeding.

Clinical Bottom Line:In patients with NSTEMI, consult with cardiology to get their preference for when to initiate anticoagulation and what agent to use (i.e. at my shop we use enoxaparin)

References:

- Bastani A et al. comparison of 30-Day Serious Adverse Clinical Events for Elderly Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department with Near-Syncope Versus Syncope. Ann Emerg Med 2018. PMID: 30529112

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Emergency Department Patients with Syncope: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med 2019. PMID: 30691921

- Chen, JY et al. Association of Parenteral Anticoagulation Therapy With Outcomes in Chinese Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA Intern Med 2018. PMID: 30592483

- Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism among Patients Hospitalized for Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1524-1531. PMID: 27797317

- Amsterdam EA et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC 2014. PMID: 25260718

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post The REBEL at Essentials of Emergency Medicine 2019 – Day 2 appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.