ED Evaluation:

Evaluation and treatment of the injured fall patient should follow standard trauma teachings, as geriatric patients can suffer the spectrum of traumatic injuries: head injuries, lacerations, hip, wrist, ankle, and humerus fractures are common. Rib fractures and pulmonary contusions are associated with higher morbidity and mortality in senior populations (Bergeron 2003). The cause of the fall should be determined when possible. Syncope and seizure should remain on the differential for all patients without a clear history for a simple mechanical fall, and can often be difficult to exclude, prompting a more extensive workup when in doubt. In those patients who are determined to have suffered a purely mechanical fall, consideration should be given toward underlying factors, including electrolyte imbalances or occult infection such as UTI, medication interactions, and mechanical impediments such as loose throw rugs and carpets throughout the house or poor lighting.

Mild hyponatremia is well-known to be associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits (Renneboog 2006). In one prospective cohort study, 15% of elderly persons in the community were found to have mild hyponatremia, and it increased their likelihood of suffering a fall more than 8 times (Gunathilake 2013). Patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease or renal insufficiency, or a history of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) are at particularly high risk for development of hyponatremia, and may benefit from electrolyte testing in the emergency department (Rittenhouse 2015). Given the prevalence of chronic hyponatremia and difficulty in detecting the same based on history and physical, a low threshold is warranted for routine electrolyte testing in this population.

Medications:

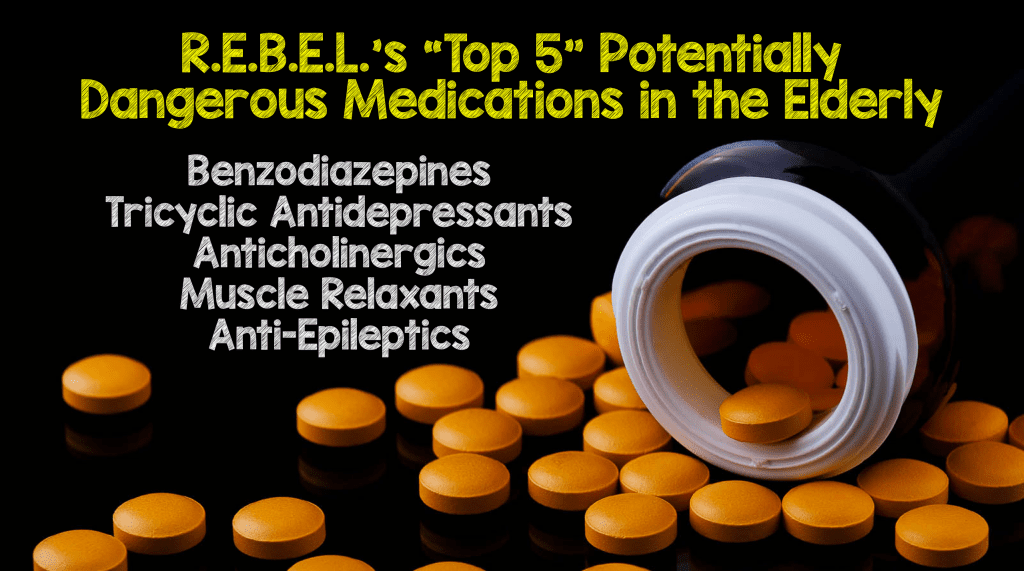

The Beers Criteria, also known as the Beers List, was originally created in 1991 and last updated in 2015 by the American Geriatrics Society. It is a list of potentially inappropriate medications that should be avoided in adults over the age of 65. Use of the medications listed on the Beers List has been found to be associated with poor health outcomes, including confusion, falls, and mortality (Counsell 2015). The Beers List is exhaustive, and at times seems to include nearly every drug we have in our armament—but the drugs listed in the Beers Criteria are there for different reasons—increased GI bleeding risk, increased risk of stroke, etc., and while it is impractical to memorize the entire list (which you can access here), there are a “top 5” that are worth focusing on, as they are easily remembered and are responsible for a troubling majority of polypharmacy-related falls in the elderly.

Risk Assessment Tools For Fall Prevention:

No single tool has been validated for use in the emergency department, however, of the many factors measured in one systematic review, four were identified as independent predictors of functional decline and repeat falls: occasional use of a walking aid, taking more than five medications per day, needing help in ADLs before the injury, and the physician’s global assessment of risk of functional decline (Sirois 2013 ). One landmark review discussed widely in the FOAM community shortly after publication (see discussion at The Skeptic’s Guide to EM, here ) suggested that while evidence-based medicine has yet to identify accurate methods to predict which senior citizens will fall in the months following an ED visit, the use of a clinical decision instrument such as the Carpenter rule, derived on community-dwelling adults for primary falls prevention (Carpenter 2009 ) or the Tiedemann rule, derived using ED patients for secondary falls prevention (Tiedemann 2010 ) may help identify those at risk for a fall (Carpenter 2014 ).

Ultimately, while there are no data to support that intervening on modifiable fall risk factors has any patient-oriented benefit, that is a function of paucity of the literature base, and not due to evidence of ineffectiveness. Certainly, the burden of disease, face value of efficacy, and low cost of intervention would suggest that any effort beyond the status quo is simply good medicine.

Tiedemann 2010 Risk Assessment Tool

Summary and Recommendations:

Falls are an important event in a senior citizen’s life, and offer the potential for significant morbidity and mortality. 15% of seniors evaluated and discharged from the emergency department with minor injuries from a fall will suffer functional decline at 3 months—difficulty with activities of daily living, grooming, bathing, and continence. 33% will fall again within the next 6 months. In the patient being discharged home from the emergency department, consider this short checklist, which can potentially make a big difference!

- Evaluate gait, balance, and mobility.

- Perform a medication reconciliation and be on the lookout for the “Top 5.”

- Consider electrolyte testing in patients at risk for hyponatremia.

- Provide patient education and information regarding secondary fall prevention.

Chris Carpenter’s Thoughts On Fall Prevention:

Thanks for tackling the topic of geriatric falls!!!

I like the review. It is 30,000 foot view but probably much more than most ED clinicians think about managing beyond the fall-related injuries. I struggle with the mission creep of EM for many things, but I really believe that proactively working to prevent future falls is self-preservation because if they fall again they’ll be right back in our already crowded ED so preventing the fall is a win-win for us and the patient.

References:

- Carpenter, Christopher R., et al. “Predicting geriatric falls following an episode of emergency department care: a systematic review.” Academic emergency medicine10 (2014): 1069-1082. PMID 25293956

- Masud, Tahir, and Robert O. Morris. “Epidemiology of falls.” Age and ageing30 (2001): 3-7. PMID: 11769786

- Bergeron, Eric, et al. “Elderly trauma patients with rib fractures are at greater risk of death and pneumonia.” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery3 (2003): 478-485. PMID: 12634526

- Renneboog, Benoit, et al. “Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits.” The American journal of medicine1 (2006): 71-e1. PMID: 16431193

- Gunathilake, Roshan, et al. “Mild Hyponatremia is Associated with Impaired Cognition and Falls in Community‐Dwelling Older Persons.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society10 (2013): 1838-1839. PMID: 24117308

- Rittenhouse, Katelyn J., et al. “Hyponatremia as a fall predictor in a geriatric trauma population.” Injury1 (2015): 119-123. PMID: 25065652Counsell, Steven R. “2015 updated AGS Beers Criteria offer guide for safer medication use among older adults.” Journal of gerontological nursing41.11 (2015): 60. PMID: 1231233

- Counsell, Steven R. “2015 updated AGS Beers Criteria offer guide for safer medication use among older adults.” Journal of gerontological nursing11 (2015): 60. PMID: 26958668

- Sirois, Marie‐Josée, et al. “Cumulative incidence of functional decline after minor injuries in previously independent older Canadian individuals in the emergency department.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society10 (2013): 1661-1668. PMID: 24117285

- Carpenter, Christopher R., et al. “Identification of fall risk factors in older adult emergency department patients.” Academic emergency medicine 16.3 (2009): 211-219. PMID: 19281493

- Tiedemann, Anne, Stephen R. Lord, and Catherine Sherrington. “The development and validation of a brief performance-based fall risk assessment tool for use in primary care.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences(2010): glq067. PMID: 20522529

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim Rezaie (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Secondary Fall Prevention in Geriatric Patients appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.