Paper: Kirchhof et al. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. NEJM 2020. PMID 32865375

Clinical Question: Does early rhythm-control or rate-control therapy reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications in patients with atrial fibrillation?

What They Did:

- Early Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation for Stroke Prevention Trial (EAST-AFNET 4)

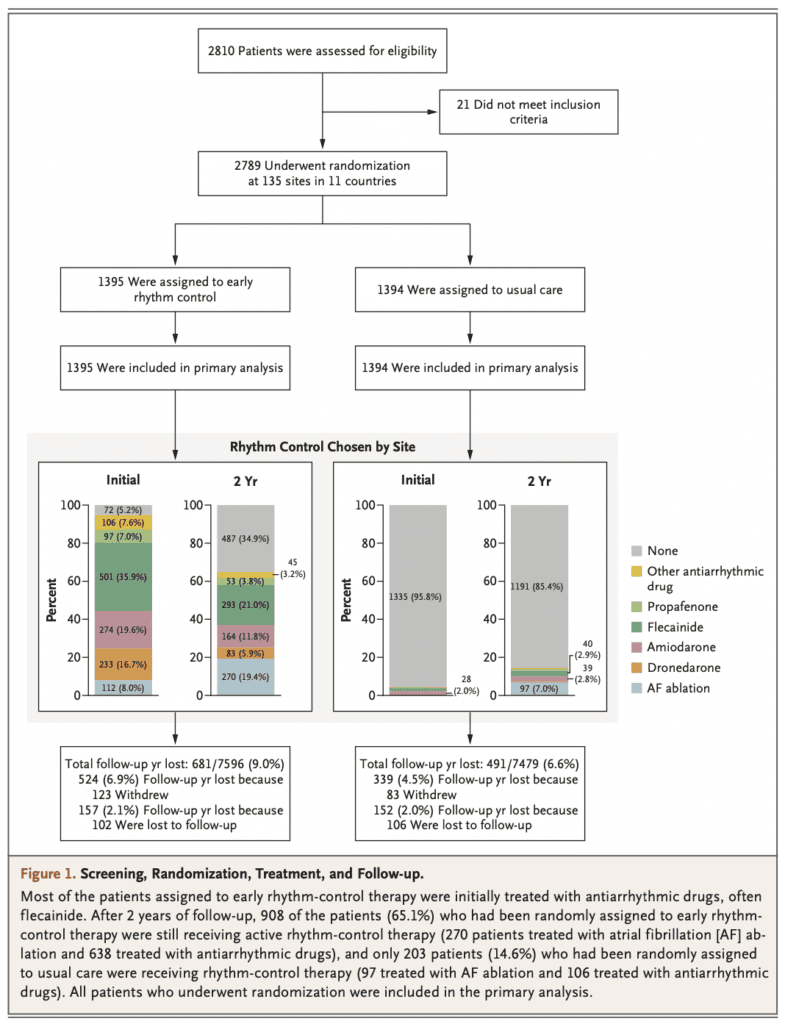

- International, investigator-initiated, parallel-group, randomized, open, blinded-outcome-assessment (PROBE) trial across 135 sites in 11 European countries between July 28, 2011, and December 30, 2016 of patients with early atrial fibrillation and concomitant cardiovascular conditions

- Random allocation of patients in a 1:1 ratio to receive early rhythm control or usual care

- Randomization stratified according to site and with variable block lengths used for concealment of assignments

- Anticoagulation and rate control were mandated in all patients

- Early rhythm-control therapy

- Local study teams chose the type of rhythm-control therapy independently (antiarrhythmic drugs, ablation as well as cardioversion)

- Patients were asked to transmit a patient-operated single-lead electrocardiogram twice per week and when symptomatic

- All abnormal ECG recordings were forwarded to the study site.

- Documentation of recurrent atrial fibrillation triggered an in-person visit from the site team

- Usual care

- Initially treated with rate-control therapy without rhythm-control therapy

- Rhythm-control therapy was used only to mitigate uncontrolled atrial fibrillation–related symptoms during adequate rate-control therapy

- At baseline, a medical history, information on clinical characteristics, therapy, symptom status, an ECG and echocardiogram were obtained

Inclusion:

- Age ≥ 18 years

- Recent-onset AF (≤ 1 year prior to enrollment)

- One of the following criteria:

- Age >75 years and a prior stroke or transient ischemic attack OR

- Two of the following: >65 years, female, heart failure (stable NYHA II or LVEF <50%), arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance, severe coronary or peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease (eGFR 15 to 59mL/min/ per 1.73m2), left ventricular hypertrophy on echocardiography (Diastolic septal wall width >15mm)

Exclusion (5 most important):

- Any disease that limits life expectancy to less than 1 year

- Prior AF ablation or surgical therapy of AF

- Previous therapy failure on amiodarone

- Patients not suitable for rhythm control of AF

- Severe mitral valve stenosis

Outcomes:

- Primary:

- Time to first occurrence of a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, stroke, or hospitalization with worsening of heart failure or acute coronary syndrome

- Number of nights spent in the hospital per year

- Important Secondary Outcomes:

- Each component of the composite primary outcome

- Quality of life (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions [EQ-5D])

- All-cause death

- AF-related death

- Time to recurrent AF

- AF burden

- Left ventricular function at 24 months

- Safety:

- Composite of death including cardiovascular death, stroke/TIA, and serious adverse events of special interest

- The components of the composite outcome, the number of serious adverse events of all types and of each type separately

Results:

- 2,789 patients randomized

- Patients enrolled a median of 36 days (Range 6 to 112d) after the 1st diagnosis of atrial fibrillation

- 1335 (95.8%) of 1394 patients in usual care were managed without rhythm control therapy , and at the end of two years 1191 of the 1394 patients (85.4%) were still not receiving rhythm-control therapy

- Sinus rhythm was found more often in patients receiving early rhythm control:

- 84.9% at 1 year vs 65.5% in usual care at 1 year

- 82.1% at 2 years vs 60.5% in usual care at 2 years

- ≈90 of patients were on anticoagulation at 2 years

- Composite of Death, Stroke or Hospitalization (Primary Outcome):

- Early Rhythm Control: 3.9 per 100 person-years

- Usual Care: 5.0 per 100 person-years

- HR 0.79; 96% CI, 0.66 to 0.94; p = 0.005

- Number of Nights Spent in the Hospital (Primary Outcome):

- Early Rhythm-Control: 5.8 +/- 21.9 days per year

- Usual Care: 5.1 +/- 15.5 days per year

- p = 0.23

- Composite of Safety Outcomes:

- Early Rhythm-Control Events: 16.6%

- Stroke: 2.9%

- Usual Care Events: 16.6%

- Stroke: 4.4%

- Early Rhythm-Control Events: 16.6%

- Death from Cardiovascular Causes:

- Early Rhythm-Control: 1.0 per 100 person-years

- Usual Care: 1.3 per 100 person-years

- HR 0.72; 96% CI 0.52 to 0.98; p =0.005

- Stroke:

- Early Rhythm-Control: 0.6 per 100 person-years

- Usual Care: 0.9 per 100 person-years

- HR 0.65; 96% CI 0.44 to 0.97; p = 0.005

- Symptoms:

- Most patients (>70%) were asymptomatic at 1 and 2 years in both treatment groups

- The change from baseline in atrial fibrillation-related symptoms (EHRA score) and quality of life (EQ-5D score) did not differ significantly between the groups

- LVF at 2 Years:

- Stable, with no evidence of significant differences between the treatment groups

Strengths:

- International, investigator-initiated, parallel-group, randomized, open, blinded-outcome-assessment (PROBE) trial across 135 sites in 11 countries

- The funders of the trial did not influence the trial design, data collection, analysis, or the decision to publish

- A follow-up time of more than 5 years

- All patients remained in follow-up from randomization until the end of the trial, death, or withdrawal from the trial.

- Blinded, central assessment of primary outcomes was used to minimize bias.

- Groups were fairly well balanced in terms of age, BMI, type of atrial fibrillation, median days since atrial fibrillation diagnosis, absence of symptoms, Baseline comorbid conditions, and previous cardioversion

Limitations:

- Large exclusion criteria, limits the population these results would apply to

- Composite primary outcome with unequal components. Death is not the same as hospitalization

- Open-label trial design in which both the researchers and the participants in the study know the treatment the participant is receiving. This could lead to bias reporting, such as adverse events

- Patients had atrial fibrillation that had recently been diagnosed (<1 year earlier), with one third of the patients having their first episode of atrial fibrillation

- 9.0% and 6.6% of follow-up years in the early-rhythm-control group and usual-care group, respectively, were lost because patients withdrew from the trial or were lost to follow-up (characteristics of the patients not presented)

- The burden of atrial fibrillation was not reported, and its role as a contributor to outcomes remains unknown

- The reported percentages of patients with sinus rhythm were probably overestimated, since they were assessed by electrocardiography rather than continuous monitoring. Additionally, detailed information on recurrent atrial fibrillation was not collected. Therefore, this trials data on percentages of patients with sinus rhythm are not comparable to data on recurrent atrial fibrillation from previous trials

- The trial was not primarily designed to assess the safety and effectiveness of specific components of early rhythm control

- Enrolled only patients with early atrial fibrillation, and thus the results may not be generalizable to patients in whom rhythm-control therapy that includes atrial fibrillation ablation is initiated later

- All enrolled patients were deemed eligible for either rate-control or rhythm-control therapy, which probably excluded the most symptomatic patients

- Atrial fibrillation ablation was used in this trial and could contribute to the superiority of early rhythm control seen in this trial

Discussion:

- Authors were looking for a between group difference of 20% in the annual rate of the primary outcomes

- Trial was stopped early at the 3rd interim analysis (75% enrollment) after a median follow-up of 5.1 years per patient

- Most patients (>70%) were asymptomatic at 1 and 2 years in both treatment groups and did not differ in left ventricular function at 2 years. This indicates that both rate control and rhythm control can control symptoms and maintain cardiac function in patients with early atrial fibrillation

- The rhythm-control approach at 2 years in the group assigned to early rhythm control was broad and somewhat evenly distributed among catheter ablation (19%), class 1c antiarrhythmic drugs, dronedarone, amiodarone, and “other” drugs.

- The use of anticoagulation was common in both groups, as well as the continuation over time (approximately 90% of patients in both groups at 2 years), and the incidence of stroke correspondingly low (0.6% of patients assigned to early rhythm control and 0.9% of patients assigned to usual care). Additionally, unlike patients in previous trials, most patients in both treatment groups in this trial continued to receive rate control, and treatment of concomitant cardiovascular conditions, maintaining their protective effects.

- While early rhythm control was associated with more adverse events related to rhythm-control therapy than was usual care, such events were uncommon. Similar to the results of other recent trials comparing rhythm-control therapies in patients with atrial fibrillation Rhythm-control-related adverse events were infrequent, occurring in 4.9% of patients in the group assigned to early rhythm control, with drug-related bradycardia the most common event. Early initiation of rhythm-control therapy, guidance on the safe use of antiarrhythmic drugs, and the availability of atrial fibrillation ablation may have contributed to the low incidence of adverse events associated with rhythm-control therapy, as compared with previous trials

Author Conclusion: “Early rhythm-control therapy was associated with a lower risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes than usual care among patients with early atrial fibrillation and cardiovascular conditions.”

Clinical Take Home Point / What Do I Tell My Patient: An association was found between early rhythm-control and reduction of AF-related adverse clinical outcomes in patients with recent atrial fibrillation diagnosis and cardiovascular disease, without affecting the number of nights spent in hospital. While early rhythm-control was associated with more adverse events, the incidence of the overall safety outcome events was similar in the two groups. The result of this trial support the use of rhythm control to reduce atrial fibrillation–related adverse clinical outcomes when applied early in the treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation.

Guest Post By:

Benjamin M. Gerretsen, MD

Emergency Medicine

Erasmus University Medical Center

Leiden, Netherlands

Twitter: @bmgerretsen

References:

- Kirchhof et al. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. NEJM 2020. PMID 32865375

- Lloyd-Jones et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004. PMID 15313941

- Wolf et al. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991. PMID 1866765

- Marini et al. Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population-based study. Stroke 2005. PMID 15879330

- Kirchhof et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: executive summary. European Heart Journal 2007. PMID 17897924

- Wyse et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. New England Medical Journal 2002. PMID 12466506

- Van Gelder et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. New England Medical Journal 2002. PMID 12466507

- Carlsson et al. Randomized trial of rate-control versus rhythm-control in persistent atrial fibrillation: the Strategies of Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (STAF) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2003. PMID 12767648

- Opolski et al. Rate control vs rhythm control in patients with nonvalvular persistent atrial fibrillation: the results of the Polish How to Treat Chronic Atrial Fibrillation (HOT CAFE) Study. Chest 2004. PMID 15302734

- Hohnloser et al. Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation–Pharmacological Intervention in Atrial Fibrillation (PIAF): a randomised trial. Lancet 2000. PMID 11117910

- Roy et al. Rhythm control versus rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. New England Medical Journal 2008. PMID18565859

- Corley et al. Relationships between sinus rhythm, treatment, and survival in the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Study. Circulation 2004. PMID 15007003

- Hohnloser et al. Effect of dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. New England Medical Journal 2009. PMID 19213680

- Nieuwlaat et al. Atrial fibrillation management: a prospective survey in ESC member countries: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. European Heart Journal 2005. PMID 16204266

- Fuster et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation). European Heart Journal 2006. PMID 16885201

- Nabauer et al. The Registry of the German Competence NETwork on Atrial Fibrillation: patient characteristics and initial management. Eurospace 2009. PMID 19153087

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post The EAST-AFNET 4 Trial: Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.