The reality unfortunately is that there is still a subgroup of patients who continue to suffer early mortality from hemorrhage, primarily because they are bleeding in the torso. This is particularly challenging for both prehospital and in-hospital clinicians to manage as these areas do not allow control through direct compression.

Enter resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) – a technique that builds on principles from vascular surgery and sees the placement of a balloon catheter into the aorta via the femoral artery. Acting as an internal tourniquet, it temporarily occludes flow to the bleeding vessel thus providing circulatory support and precious time to get the patient to definitive care.

With the alternative being death from hemorrhage, REBOA came as a breath of fresh air – a minimally invasive means of achieving hemorrhage control in these extremely sick patients. There were innovators and early adopters and reports of fantastic saves – patients were surviving who would never have survived before.

But then came the reports of complications, primarily limb ischemia and multisystem organ failure. The initial equipment was also cumbersome and risky to place, and so many sat on the sidelines watching these early adopters do their thing. With time came improvements in the equipment, and more centers joined the bandwagon, some even pushing this prehospital. Of course, on the flip side, there remain the staunch nay-sayers.

Continued debate is good (and necessary) especially for a high-stakes procedure like REBOA. You only have to turn to Twitter to see how much controversy and angst this procedure still brings up – the reality is there are still few clear answers or (completed) high quality trials answering questions like: who is the right patient; how long can the balloon remain up in humans; what is the right setting to do this in; what are the actual outcomes when compared to usual care?

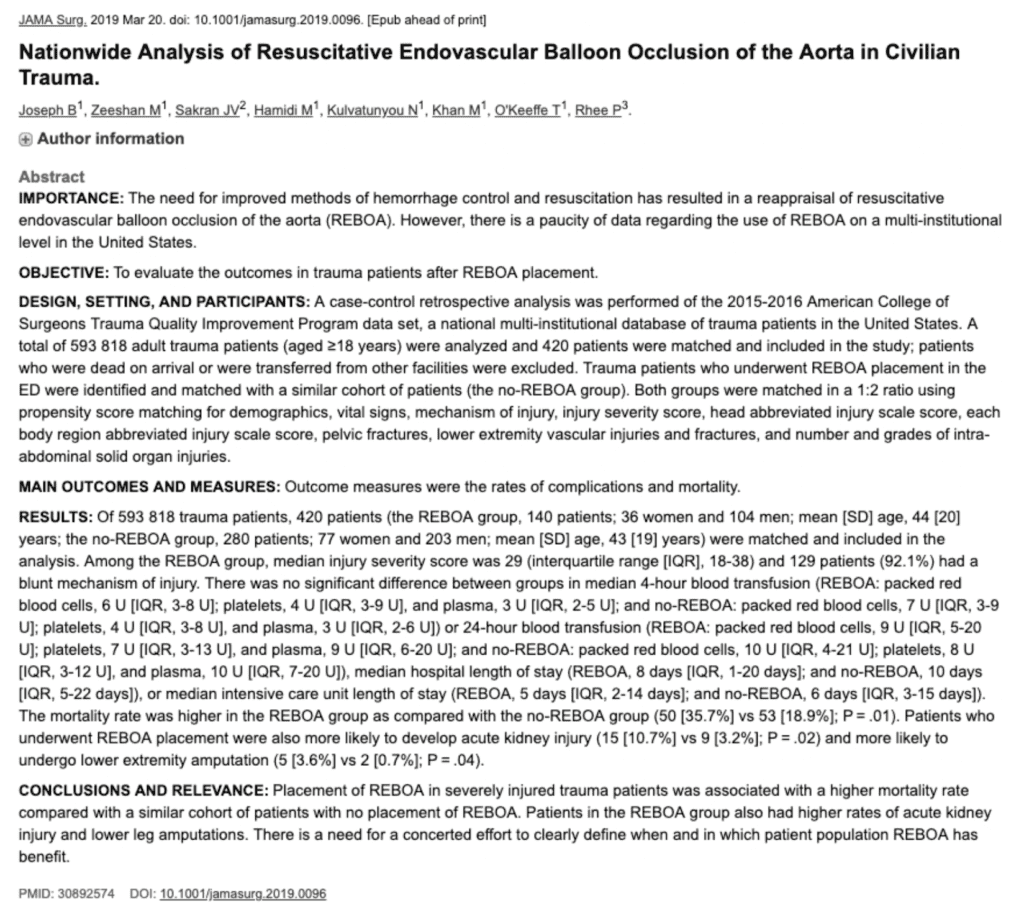

This week we saw the publication in JAMA Surgery of a paper by Dr. Joseph et al from the United States. He had presented the initial data at the AAST meeting held in September 2018, and the full paper was eagerly awaited. The real important aspect of this study, in my mind, is that it was designed to compare REBOA to “standard care” – more on this later.

The abstract is below but it is, as always, very important to read the actual paper in full and ultimately decide for yourself what it tells us.

What kind of paper is this?

This is a retrospective case-control analysis of data in the American College of Surgeons-Trauma Quality Improvement Program(ACS-TQIP) database. This program works to ensure quality standards amongst US trauma centers, and includes data from over 800 hospitals. Individual centers can compare how they are doing in accordance to national standards.

What did the authors do?

The authors looked through the database from 2015-2016, and identified adult trauma patients who received REBOA within one hour of presentation to the trauma center. They excluded patients arriving in arrest, those that were transferred, those with missing physiologic data, and those who underwent thoracotomy.

Of almost 594,000 patients (primarily suffering blunt injury), they were able to find 140 patients who underwent REBOA. These patients were more likely to have lower presenting blood pressures, higher injury severity scores, and lower GCS than non-REBOA patients overall.

They then propensity-matched a cohort of patients with similar demographics, severity score, vital signs, injury mechanism, injury pattern, and injury severity scores in a 1:2 ratio, to obtain 280 patients in the control group – these received “standard care”. The table shows they did a pretty reasonable job at this.

There is a need for a concerted effort to clearly define when and in which patient population REBOA has benefit. https://t.co/DcAfjw9azs

— JAMA Surgery (@JAMASurgery) March 23, 2019

The primary outcomes they sought were mortality in the ED, at 24 hours, and after 24 hours, with secondary outcomes of transfusion requirements (at 4 and 24 hours), complications in-hospital (to include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure, myocardial infarction, compartment syndrome or amputation of the limb, and unplanned return to the operating room), ICU length of stay (LOS) and hospital LOS.

What did they find?

The headline figures are that there was significantly higher 24-hour mortality (26.4% vs 11.8 p=0.01), rates of acute kidney injury (10.7% vs 3.2% p=0.02) and lower limb amputation (3.6% vs 0.7% p=0.04) in the REBOA group than the no-REBOA group. There was no significant difference in blood transfusion requirements at 4 and 24 hours, nor in ICU or hospital LOS. All other secondary outcome measures also showed no significant difference.

An additional finding was that time from ED to intervention (either interventional radiology angioembolization or laparotomy) appeared significantly longer in the REBOA group.

Finally, they reported on the subgroup of REBOA patients who survived against those who subsequently died. The survivors had significantly higher mean SBP (114 vs 98mmHg p=0.006) and GCS (15 vs 3 (p=0.04), and lower heart rate (99 vs 109 beats/minute p=0.02), lower ISS (27 vs 38 p=0.043) and blood product requirements (24-hour PRBC requirement 1U vs 14U p<0.001), and were less likely to have a major liver injury (24.4% vs 42% p=0.04) – or in other words those who died in this subgroup were a much more critically injured bunch.

What do the authors conclude – and can we take that at face value?

The authors conclude that “placement of REBOA in severely injured trauma patients was associated with higher mortality compared with a similar cohort of patients who did not undergo REBOA placement.” They go on to highlight the higher complication rates in the REBOA group.

Some have touted this study as a nail in the coffin for REBOA. But is this really what we can conclude – in 2019 – from this study? Personally, I feel the headlines on this article in social media and elsewhere are not fully supported by the study for these reasons:

- The ACS:TQIP database is a fantastic tool – but it only records initial blood pressure and heart rate. Hence the response to initial resuscitation cannot be measured from that dataset, nor was it in this study. Even though the authors go to great pains to propensity match a cohort of patients with similar initialvital signs, if that patient then goes on to respond to a liter of fluid or a unit of blood, they are no longer a non-responder, and hence are no longer a patient in whom REBOA is indicated. There is no way for us to determine that responder group from this paper. The authors, to their credit, do acknowledge this limitation, but this to me is the biggest flaw in the methodology.

- There was no means to determine duration of aortic occlusion. This is a critical piece of information – occlusion times, especially in zone 1, need to be kept to a minimum. Inevitably, those with prolonged occlusion times will suffer ill effects downrange. It is impossible to identify this from the dataset used, and yet this information is vital to have a clear understanding of the outcomes from REBOA.

- The time period the authors looked at (2015-2016) reflected a very different way REBOA was implemented to what it is in 2019 (albeit we are still in many ways defining the use). Importantly, the big move in the US about mid-2016 was to go from the large (at least 12-French) sheath and device to the lower profile 7-French system. This smaller system only got approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2015, and it took several months for it to then come into use at centers doing REBOA. We know that smaller sheath devices lead to lower (though not negligible) access site and limb ischemic complications, and so it is not that surprising to see the higher limb ischemic complications in the REBOA cohort of this paper.

- If you look at the patients who got REBOA, you have to question why those with SBP>80mmHg were even getting this. Likely these people did not need REBOA and this can certainly skew outcomes

- The subgroup of patients who got REBOA and died was a lot sicker cohort than those who got it and lived. There are significant differences in initial SBP, GCS, and blood product requirements. Did these people die because of REBOA – or did they die because their injuries were so severe from the outset? Or was it something else completely? The presented data makes it difficult to conclude which factor may be most responsible.

- The majority of patients included suffered blunt injuries. Would a group that had a primarily penetrating mechanism of injury have fared differently – again difficult to conclude from this dataset and not accounted for by the study.

- Despite contributions to the ACS:TQIP database from almost 800 centers and almost 594,000 individual patient records, only 140 had undergone REBOA. It is unfortunate that the sample size is so low. However, again reflecting practice in 2015, the majority of REBOA procedures were being done at a very small number of centers, and this certainly skews the data in this paper.

- The use of REBOA in general in 2019 is much different than it was in 2015-2016. Not only are more centers utilizing it, but newer concepts such as partial REBOA are being implemented, and this may ameliorate some of the complications highlighted in this paper.

I do however applaud the authors for undertaking this study and I think we can take away some important points:

- It is imperative that we continue to study this evolving technique – but we must develop well-conducted multicenter trials to do so

- I was glad to see the comparator being “standard care” in this study – this is what we need.Prior trials comparing to resuscitative thoracotomy, for example, can be somewhat misleading. Thoracotomy has its own unique indications and REBOA is not a complete replacement of it.

- One of the interesting data points from this study was the increased time to intervention in the REBOA group. This is important and needs to be considered by individual centers. In some scenarios, it may be prudent to utilize those extra minutes to provide temporary hemorrhage control in a patient who would otherwise imminently exsanguinate and die. However, in some patients it will clearly be to their detriment to delay movement to definitive care (especially if the indication for placement has not been correctly considered). This goes back again to our discussion around appropriate patient selection

- We need to focus more on our post-procedure management of these patients. When REBOA is truly indicated, does our post-procedure management affect morbidity and mortality? Are we being cautious enough about monitoring for limb ischemia, removing the sheath appropriately, managing the peri-operative and early intensive care phases of these patients well?

So “nail in the coffin” for REBOA this study is not – but rather a call to arms that if we are to continue using this modality (and it looks like we are for now), then we should continue the debate and support development of high-quality trials to, as the authors state, “clearly define when and in which patient population REBOA has benefit.”

Best

Zaf

Post Written By:

Zaf Qasim, MBS, FRCEM, EDIC

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Critical Care

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Twitter: @emeddoc

References:

- Harris T et al.The evolving science of trauma resuscitation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2018:85-106 PMID 29132583

- Morrison JJ, Rasmussen TE. Noncompressible torso hemorrhage: a review with contemporary definitions and management strategies. Surf Clin North Am 2012:843-858 PMID: 22850150

- Gamberini E et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in trauma: a systematic review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg 2017 PMID: 28855960

- Davidson AJ et al. The pitfalls of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: Risk factors and mitigation strategies. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018:192-202 PMID: 29266052

- Joseph B et al. Nationwide analysis of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in civilian trauma. JAMA Surg 2019 PMID: 30892574

- Teeter WA et al. Smaller introducer sheaths for REBOA may be associated with fewer complications. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016:1039-1045 PMID: 27244576

- Brohi K et al.Why are bleeding trauma patients still dying? Intensive Care Med 2019 PMID: 30741331

- Qasim ZA, Sikorski RA. Physiologic considerations in trauma patients undergoing resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. Anesth Analg 2017:891-894 PMID: 28640785

This post was also cross posted at St. Emlyn’s Blog

Post Peer Reviewed By: Simon Carley, MD (Twitter: @EMManchester) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post JC: Time to put the REBOA Balloon Away? Maybe, Maybe Not… appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.