Every year there are 6 million visits to the Emergency Department (ED) for chest pain, and approximately 2 million hospital admissions each year. This is approximately about 10% of ED visits and 25% of hospital admissions with 85% of these admissions receiving a diagnosis of a non-ischemic etiology to their chest pain (CP). This over triage has enormous economic implications for the US health care system estimated at $8 billion in annual costs.

Every year there are 6 million visits to the Emergency Department (ED) for chest pain, and approximately 2 million hospital admissions each year. This is approximately about 10% of ED visits and 25% of hospital admissions with 85% of these admissions receiving a diagnosis of a non-ischemic etiology to their chest pain (CP). This over triage has enormous economic implications for the US health care system estimated at $8 billion in annual costs.

Why do we do this?

Well, it could be that the single greatest contributor to financial losses in malpractice claims against emergency physicians comes from failure to accurately diagnose acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

So the question is:

Are there specific aspects of the history that can increase or decrease the likelihood that a patient has acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or AMI?

There are 5 studies that were recommended by Dr. Amal Mattu, on his EMCast Podcast (July 2012) that evaluated the components of history that were more likely to correlate with ACS and/or AMI. Each will be reviewed below.

| Study | Number of Patients |

| Edwards et al., 2011 | 3306 |

| Body et al., 2010 | 796 |

| Swap et al., 2005 | Literature Review |

| Goodacre et al., 2002 | 893 |

| Panju et al. , 1998 | Literature Review |

Edwards M et al. Ann Emerg Med 2011 [1]

The main objective was to see if there was any correlation between severity of CP and the risk of AMI at presentation, or composite end points (death, revascularization, or acute myocardial infarction) at 30 days. Severe chest pain was defined as 9 – 10 on a pain scale of 0 to 10.

- Risk of AMI with Pain Score of 1 – 8 (82% of patients) = 3.0%

- Risk of AMI with Pain Score of 9 – 10 (18% of patients) = 3.9%

- Not statistically significant different

- Bottom Line: Severity of pain is not related to likelihood of AMI at presentation, or composite end points (death, revascularization, or AMI) at 30 days.

Body R et al. Resuscitation 2010 [2]

- Strongest positive predictor of AMI

- Diaphoresis with CP

- Other positive predictors of AMI and adverse events

- Nausea and vomiting with CP

- CP with radiation to both shoulders > right shoulder > left shoulder

- Central chest pain

- Strongest negative predictor of AMI

- Pain located in the left anterior chest

- Other negative predictors of AMI and adverse events

- CP described as pain being the same as previous AMI

- Presence of CP at rest

- Bottom Line: Many “atypical” symptoms are more likely to render the diagnosis of ACS than traditional “typical” symptoms

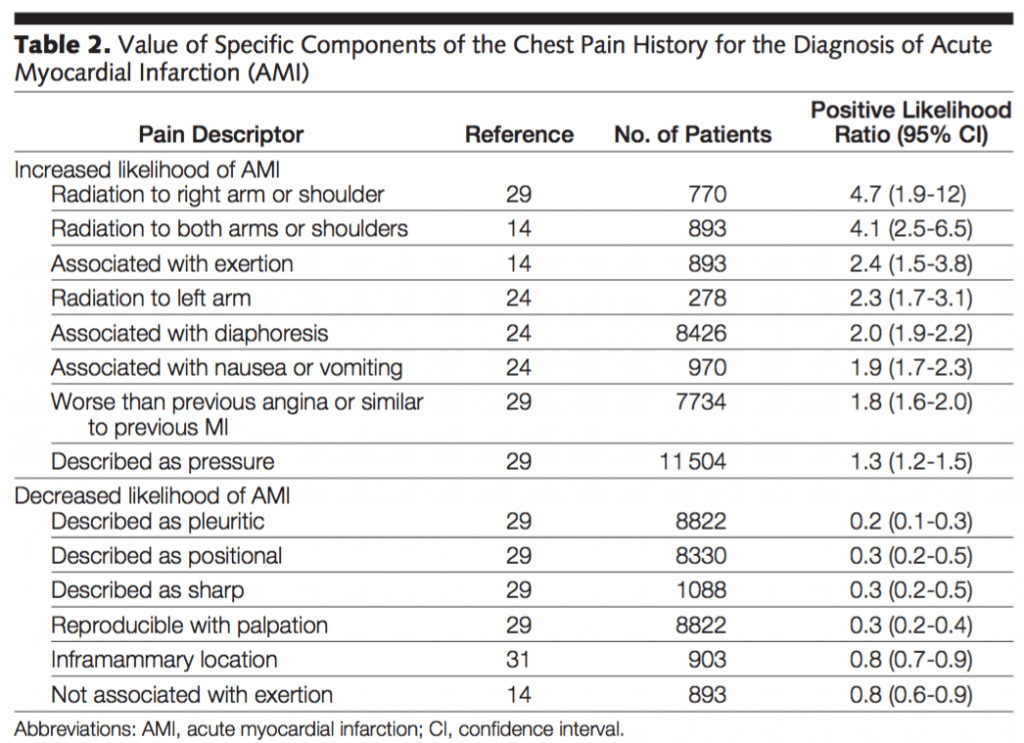

Swap CJ et al. JAMA 2005 [3]

The authors wanted to identify the elements of a CP history that might be most helpful to the clinician in identifying ACS. They performed a literature search from 1970 to 2005.

- Bottom Line: No characteristics of chest pain alone, or in combination, identify a group of patients that can be safely discharge home without further diagnostic testing. Also beware the chest pain which radiates to the RIGHT shoulder (LR = 4.7).

Goodacre S et al. Acad Emerg Med 2002 [4]

In this prospective, observation cohort study of 893 patients, the authors assessed the performance of clinical features used in the diagnosis of CP, specifically in patients who were clinically stable and had a non-diagnostic EKG.

- Predictive of ACS/AMI:

- Exertional pain

- Pain radiating to both arms > right arm

- NOT predictive of ACS/AMI:

- Presence of chest wall tenderness

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diaphoresis

- Bottom Line: Clinical features have a limited role in triage decision-making for ACS/AMI.

Panju AA et al. JAMA 1998 [5]

- Bottom Line: History alone can help, but can NOT rule out ACS/AMI!

Clinical Bottom Line:

- CP radiating bilaterally > right > left

- Diaphoresis associated with CP

- N/V associated with CP

- Pain with exertion

Clinical factors that DECREASE likelihood of ACS/AMI:

Chest pain that is:

- Pleuritic

- Positional

- Sharp, stabbing

- Reproducible with palpation

References:

- Edwards M et al. Relationship Between Pain Severity and Outcomes in Patients Presenting with Potential Acute coronary Syndromes. Ann Emerg Med 2011. PMID: 21802776

- Body R et al. The Value of Symptoms and Signs in the Emergent Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Resuscitation 2010. PMID: 20036454

- Swap CJ et al. Value and Limitations of Chest Pain History in the Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Acute Coronary Syndromes. JAMA 2005. PMID: 16304077

- Goodacre S et al. How Useful are Clinical Features in the Diagnosis of Acute, Undifferentiated Chest Pain? Acad Emerg Med 2002. PMID: 11874776

- Panju AA et al. The Rational Clinical Examination. Is this Patient Having a Myocardial Infarction? JAMA 1998. PMID: 9786377

The post Chest Pain: What is the Value of a Good History? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.