The Novel Coronavirus 2019, was first reported on in Wuhan, China in late December 2019. The outbreak was declared a public health emergency of international concern in January 2020 and on March 11th, 2020, the outbreak was declared a global pandemic. The spread of this virus is now global with lots of media attention. The virus has been named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes has become known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This new outbreak has been producing lots of hysteria and false truths being spread, however the data surrounding the biology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics are growing daily, making this a moving target. This post will serve as a summary of cardiovascular considerations in regards to COVID-19.

The Novel Coronavirus 2019, was first reported on in Wuhan, China in late December 2019. The outbreak was declared a public health emergency of international concern in January 2020 and on March 11th, 2020, the outbreak was declared a global pandemic. The spread of this virus is now global with lots of media attention. The virus has been named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes has become known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This new outbreak has been producing lots of hysteria and false truths being spread, however the data surrounding the biology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics are growing daily, making this a moving target. This post will serve as a summary of cardiovascular considerations in regards to COVID-19.

To go back to the main post, click on the image below…

Cardiovascular Considerations[1]

This paper is divided into 5 parts:

- Prevalence of CVD in Patients with COVID-19

- Cardiovascular Sequalae

- Drug Therapy

- Considerations for Health Care Workers

- Considerations for Health Systems and Management of Non-Infected Cardiovascular Patients

Prevalence of Cardiovascular (CVD) Disease in Patients with COVID-19:

- Prevalence (Hard to know exact prevalence due to lack of testing):

- HTN: 17.1%

- Cardiac/Cerebrovascular Disease: 16.4%

- Diabetes Mellitus: 9.7%

- Case-Fatality Rates (Mostly out of China):

- CVD: 10.5%

- DM: 7.3%

- HTN: 6.0%

- Overall: 2.3%

- CVD may be a marker of accelerated immunologic aging/dysregulation

- 21 patients positive for COVID-19 infection [2]

- Cardiomyopathy Prevalence: 33.3%

Cardiovascular Sequelae

Cardiovascular Considerations

- Acute Myocardial Injury Prevalence:

- Hospitalized: 7 – 17%

- ICU: 22.2%

- Death: 59.0%

- True prevalence most likely under reported given logistical challenges associated with limited testing and cardiac catheterization lab availability

- Cardiac Arrhythmias

- Presentation: 7.3%

- Non-ICU: 6.9%

- ICU: 44.4%

- Specifics of type of cardiac arrhythmias not yet known

- Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure

- Heart Failure Prevalence: 23.0%

- Unclear if this is due to pre-existing LV dysfunction or new cardiomyopathy

- Cardiogenic/Mixed Shock

- COVID-19 presentation is typically respiratory illness, which can lead to ARDS and hypoxemia, but similar features can be seen with coexisting cardiogenic pulmonary edema

- Historically, right heart catheterization is used to determine pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, but not currently part of the Berlin criteria for diagnosis of ARDS

- BNP and echocardiography can be helpful, but not always definitive in clarifying diagnosis

- ARDS vs Cardiogenic shock distinction is important, as this can change the management of ECMO in facilities that have it available (VV vs VA respectively)

- In a case series of 52 critically ill patients with COVID-19, 83.3% (5/6) treated with ECMO did not survive

- VTE

- Just because we don’t talk about PE enough, COVID-19 infection can increase risk of VTE (There are currently no published studies to verify this)

- Vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction can contribute to hypercoaguable state

- Elevated D-dimer (>1g/L) can be associated with increased risk of in-hospital death

- The optimal thromboprophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is not known. Therefore, use contemporary guideline endorsed strategies

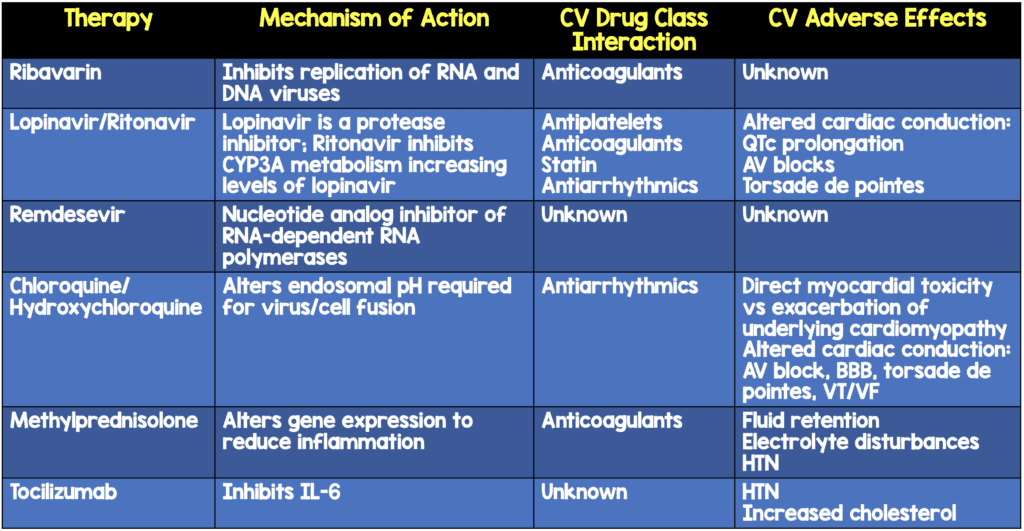

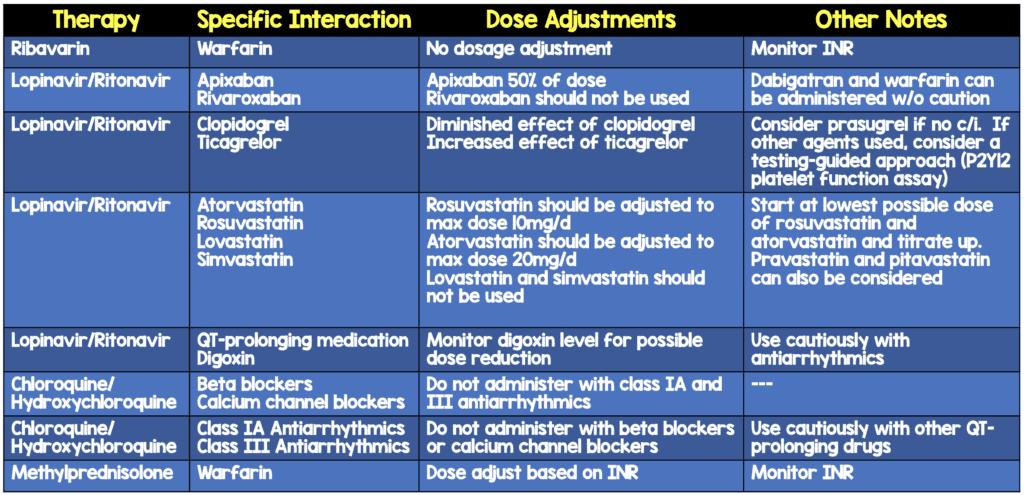

Drug Therapy

- Currently no approved treatments for COVID-19, but many under study

- Antiviral Therapy and Other Treatments

- ACE2 and Potential Therapeutic Implications

- ACEI/ARBs may upregulate ACE2 increasing susceptibility to the virus

- ACEI/ARB may also potentiate lung protective functions of ACE2

- Implications unclear at this time

Considerations for Health Care Workers

- Transmission:

- Mostly via respiratory droplets and contact

- Only patients requiring aerosol-generating procedures require airborne isolation

- TEE, Intubation, CPR, and BVM recommendation is CAPR/PAPR instead of N95

- CDC and WHO recommend standard, contact precautions with face mask, eye protection, gown, and gloves in addition to above

- In the setting of cardiac arrest: Mechanical CPR > Manual CPR

- Cancel elective cardiac procedures

- Convert cath labs into negative pressure rooms

Considerations for Health Systems and Management of Non-Infected Cardiovascular Patients

- Hospital surges:

- Prioritize the treatment of severe and high-risk patients but also consider:

- Reports of centers developing alternate STEMI pathways in the setting of COVID-19: fibrinolytic therapy if delays to PCI

- Repurposing cardiac ICUs as medical ICUs will likely become necessary

- To minimize ICU bed utilization, consider:

- Percutaneous coronary interventions > CABG

- Transcatheter valve procedures > surgery

- Ethical challenges:

- Do we consider all patients alike vs triaging patients according to age, comorbidities, and expected prognosis (i.e. wartime triage)?

- Prioritize the treatment of severe and high-risk patients but also consider:

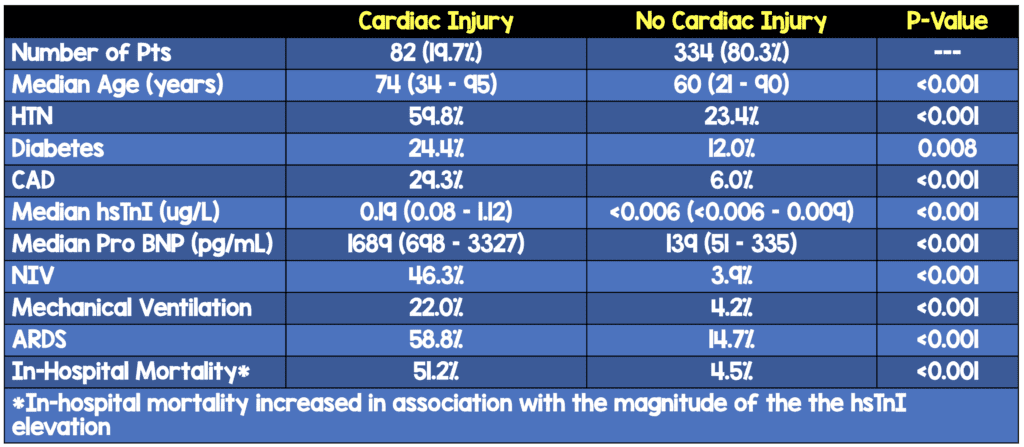

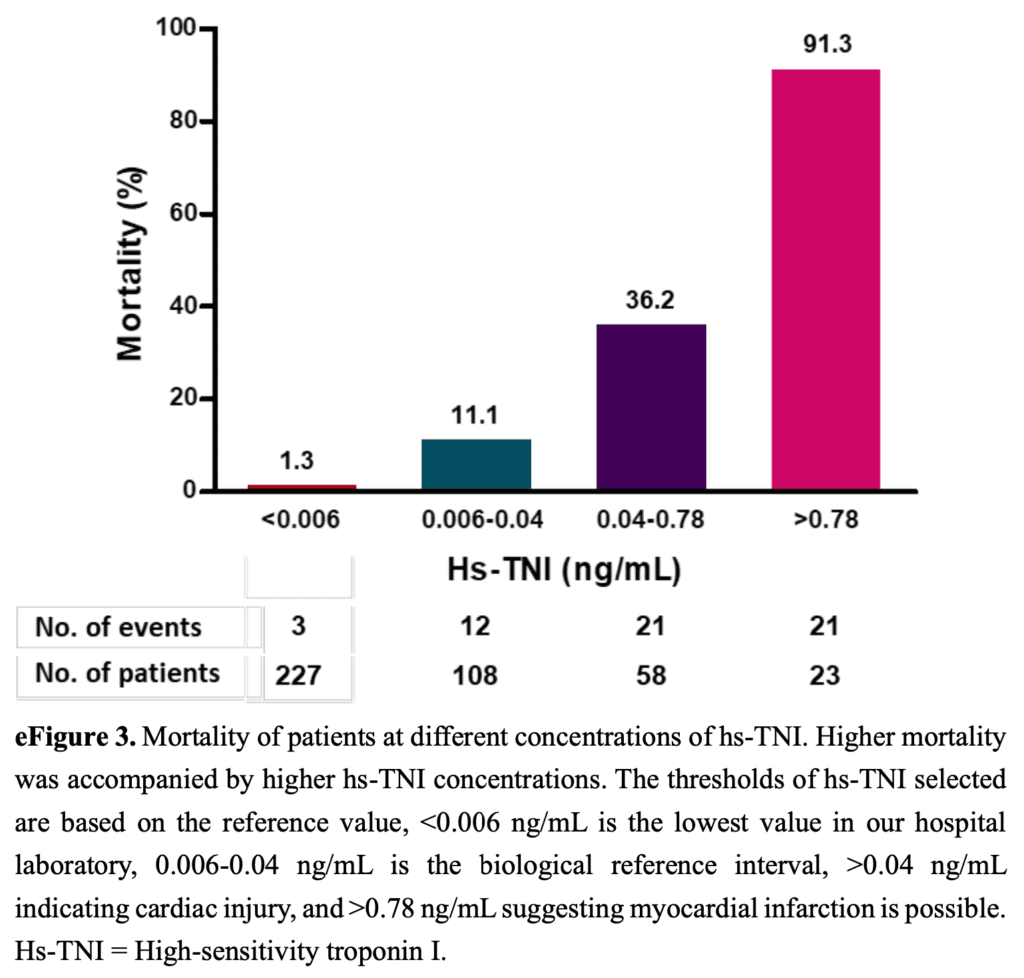

Incidence and Significance of Cardiac Injury in Patients with COVID-19 [3]

- Retrospective cohort study of 416 consecutive pts

- Of the patients with Cardiac injury

- Only 22 (26.8%) had ECG performed

- 14/22 (63.6%) ECGs were all abnormal with findings compatible with myocardial ischemia: T wave depression/inversion, ST-segment depression, & Q waves

- Bottom Line: Cardiac injury is common in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and associated with higher risk of in-hospital mortality

Case Series of 4 Patients with COVID-19 in New Orleans [5]

- Autopsies of 4 patients with COVID-19

- Gross Pathology:

- Most significant gross findings were cardiomegaly and right ventricular dilatation

- Coronary arteries showed no significant stenosis or acute thrombus

- Microscopic Pathology:

- Myocardium did not show any large or confluent areas of myocyte necrosis

- Scattered individual cell myocyte necrosis in all cases

- Lack of myocarditis

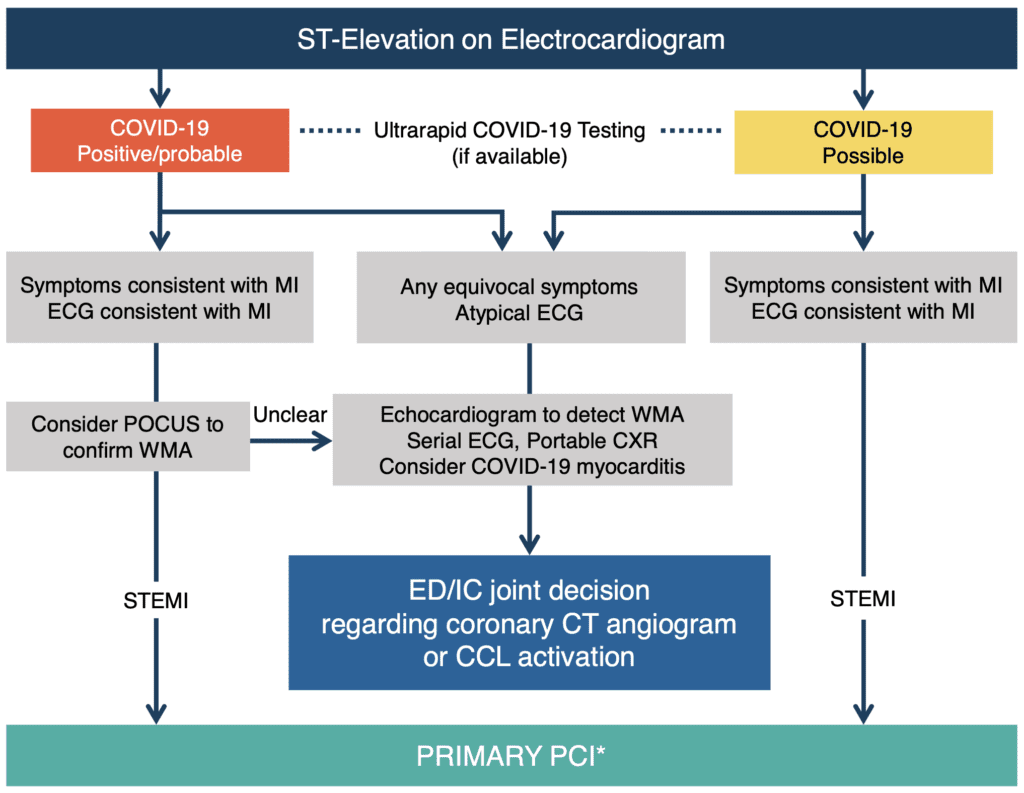

Recommendations from the ACC on STEMI [4]

- Elective patients: In order to persevere hospital bed capacity, resources, and avoid exposure to patients/healthcare workers it is reasonable to avoid elective procedures

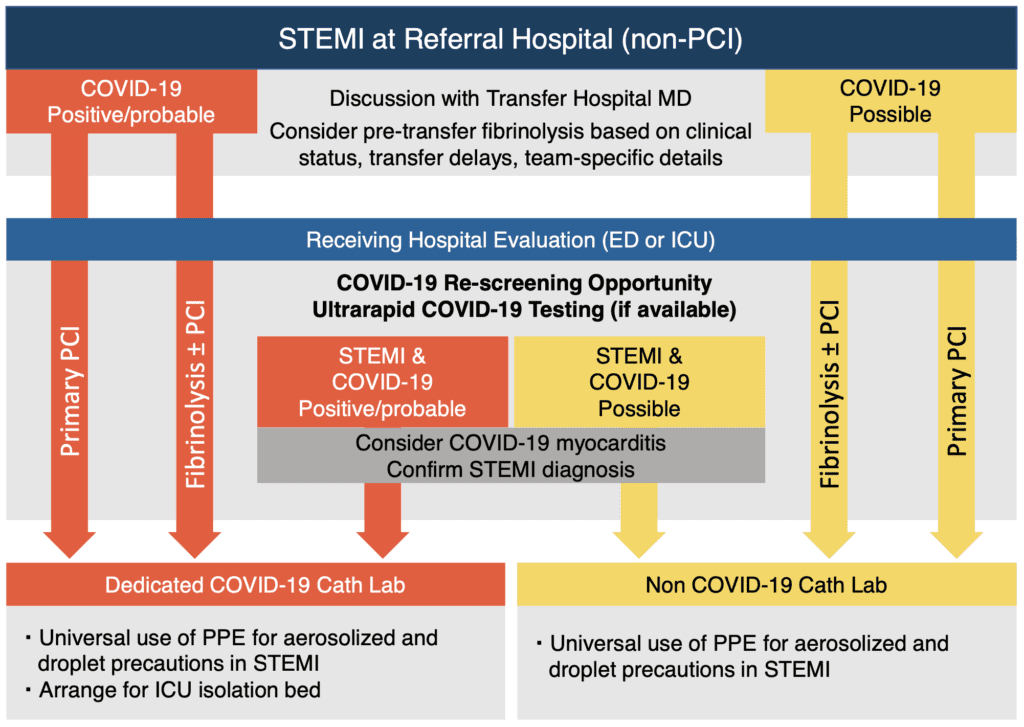

- STEMI: In patients with known COVID-19 and STEMI, the balance of staff exposure and patient benefit will need to be weighed carefully. Fibrinolysis can be considered an option for the relatively stable STEMI patient with active COVID-19

- NSTEMI: For most patient with NSTEMI and suspected COVID-19, timing should allow for diagnostic testing for COVID-19 prior to cardiac catheterization and allow for a more informed decision regarding infection control

Made up Pt: HD Stable + STEMI + Suspected #COVID19. What should be done?#COVID19FOAM

— Salim R. Rezaie, MD (@srrezaie) March 28, 2020

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), and American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Position Statement on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction (Published April 20th, 2020) [7]

- “Primary PCI remains the standard of care for STEMI patients at PCI capable hospitals when it can be provided in a timely fashion, with an expert team outfitted with PPE in a dedicated CCL.”

- “Fibrinolysis-based strategy may be entertained at non-PCI capable referral hospitals or in the specific situations where primary PCI cannot be executed or is not deemed the best option.”

- Definite STEMI

- Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the standard of care for patients presenting to PCI centers (within 90min of first medical contact) in patients with confirmed or probable COVID-19

- Primary PCI is superior for establishing normal (TIMI grade 3) coronary flow compared to an initial fibrinolysis strategy has a significantly lower risk of fatal and nonfatal bleeding complications

- “STEMI-Mimickers” (i.e. myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy). Fibrinolysis of these patients would provide no benefit to the patient, but still incur bleeding risk and eventual invasive diagnostic catheterization given that the ST-elevation is unlikely to resolve.

- STEMI from Non-PCI Capable Hospital

- If rapid reperfusion with primary PCI is not feasible, a pharmacoinvasive approach is recommended with initial fibrinolysis followed by considerations of transfer to a PCI center

- Fibrinolysis within 30min of STEMI diagnosis, and transfer for rescue PCI when necessary may be preferable for all COVID-19 positive stems patients who are at a referral hospital provided the diagnosis of true STEMI is highly likely

- In the US, an initial fibrinolysis therapy can be used in non-PCI capable hospitals if the first medical contact to repercussion is felt to be >120min

STEMI at PCI Capable Facility

STEMI at Non-PCI Capable Facility

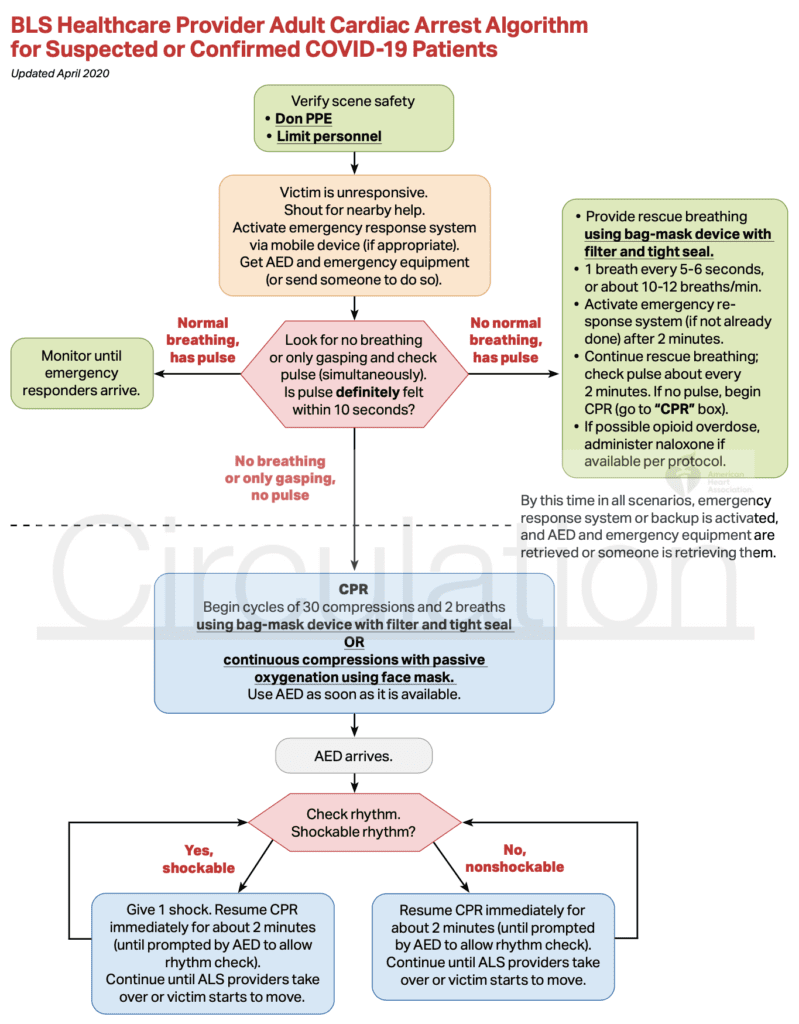

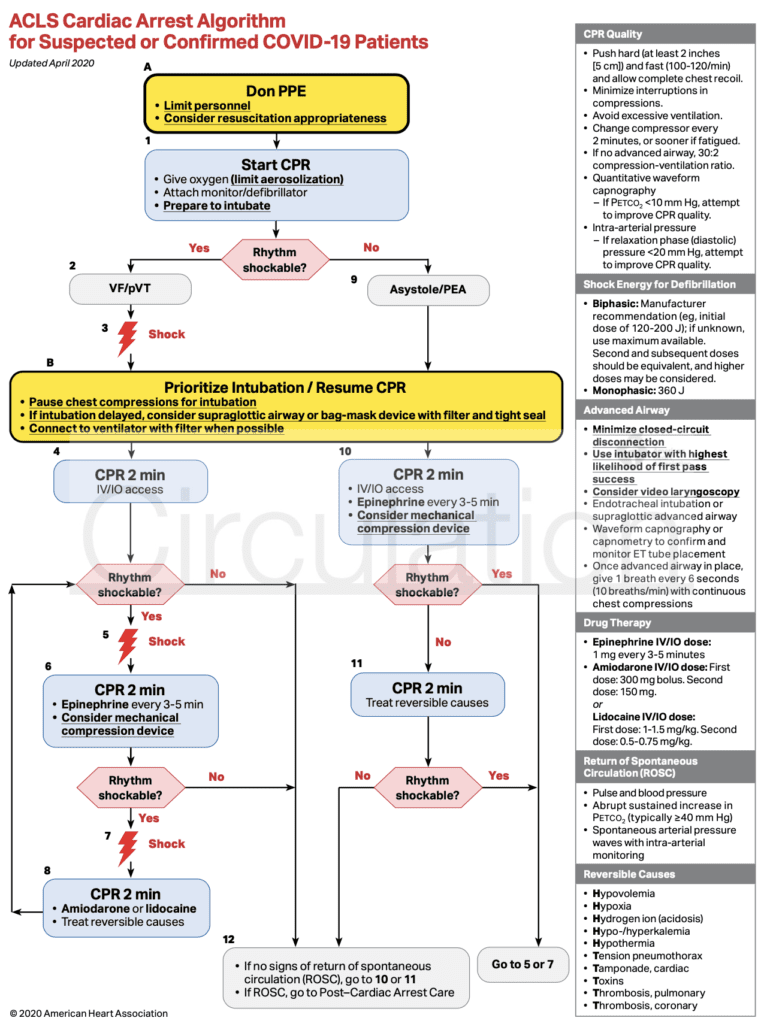

Cardiac Arrest

- No recommendations made

-

AHA Recommendations for Suspected or Known COVID-19 and Cardiac Arrest :

- Use Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs)

- If AIIR not available use single person room with the door closed

- Limit number of providers in room

- Aerosol-generating procedures = CPR, endotracheal intubation, NIV

- Require respiratory protection = N95/PAPR + gown + gloves + eye protection + face shield + hand hygiene

- Consider intubating first in patients with acute respiratory failure

- If intubation needed use RSI

- If possible, avoid procedures which generate aerosols (i.e. BVM, nebulizers, NIPPV)

- Should avoid HFNC and mask CPAP or BiPAP due to greater risk of aerosolization

- Clean and disinfect room after procedural support

- Use Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs)

-

AHA Guidance for EMS and Other First Responders:

- Dispatchers should identify signs/symptoms/risk factors for COVID-19

- This should not supersede pre-arrival instructions when immediate lifesaving interventions are required (CPR or Heimlich maneuver)

- EMS should be notified in advance that they may be caring for, transporting or receiving a patient who may have COVID-19

- If dispatchers advise EMS of suspected COVID-19 patient:

- Respiratory protection = N95 or PAPR + gown + gloves + eye protection + face shield + hand hygiene

- If dispatchers do not advise EMS of suspected COVID-19 patient:

- Follow standard procedures

- Patients with respiratory symptoms should wear a medical mask for source control

- If nasal cannula is being used a medical mask or NRB mask should be placed over the patients face

- During transport limit number of providers in patient compartment to essential personnel

- Aerosol-generating procedures = CPR, endotracheal intubation, NIV

- BVMs and other ventilatory equipment should have HEPA filtration for expired air

- Special considerations:

- EMS should notify receiving healthcare facility if patient has an exposure

- Keep patient separated from other people as much as possible (i.e. family)

- Dispatchers should identify signs/symptoms/risk factors for COVID-19

-

AHA Guidance for BLS, ACLS, & PALS [Link is HERE]

- PDF: AHA BLS, ACLS, & PALS Recs

- Interesting Note on Prone CPR: “While the effectiveness of CPR in the prone position is not completely known, for those patients who are in the prone position with an advanced airway, avoid turning the patient to the supine position unless able to do so without risk of equipment disconnections and aerosolization. Instead, consider placing defibrillator pads in the anterior-posterior position and provide CPR with the patient remaining prone with hands in the standard position over the T7/10 vertebral bodies.”

-

IHCA Outcomes Among Pts with COVID19 Pneumonia in China [6]

- Retrospective Review of 136pts

- Resp Etiology = 87.5%

- Most Common Initial Rhythm = Asystole 89.7%

- ROSC = 13.2%

- 30d Survival = 2.9%

- Good Neuro Outcome = 0.7%

-

My Conclusion:

- DON PPE for all Team Members

- No PPE = No Code

- Intubated Pts + Code = Consider Not Coding

Treatment Recommendations for COVID-19: Infection Risk to Rescuers from Patients in Cardiac Arrest via the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR)

- We suggest that chest compressions and cardiopulmonary resuscitation have the potential to generate aerosols (weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence).

- We suggest that in the current COVID-19 pandemic lay rescuers consider compression-only resuscitation and public-access defibrillation (good practice statement).

- We suggest that in the current COVID-19 pandemic, lay rescuers who are willing, trained and able to do so, may wish to deliver rescue breaths to children in addition to chest compressions (good practice statement).

- We suggest that in the current COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals should use personal protective equipment for aerosol generating procedures during resuscitation (weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence).

- We suggest it may be reasonable for healthcare providers to consider defibrillation before donning aerosol generating personal protective equipment in situations where the provider assesses the benefits may exceed the risks (good practice statement)

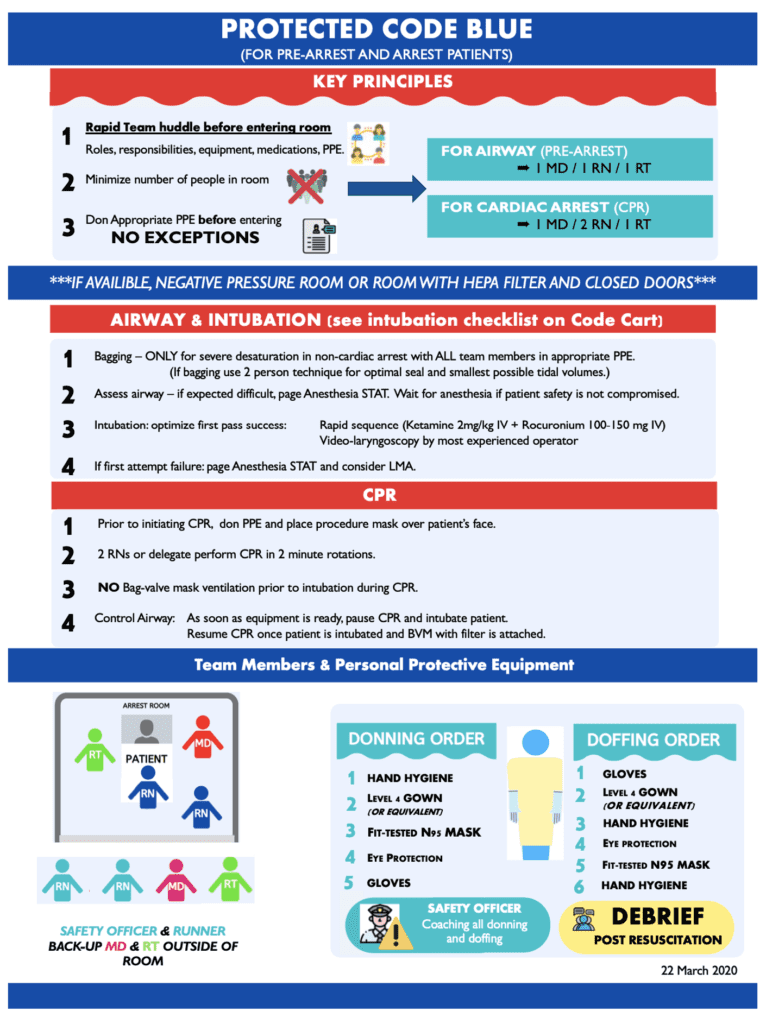

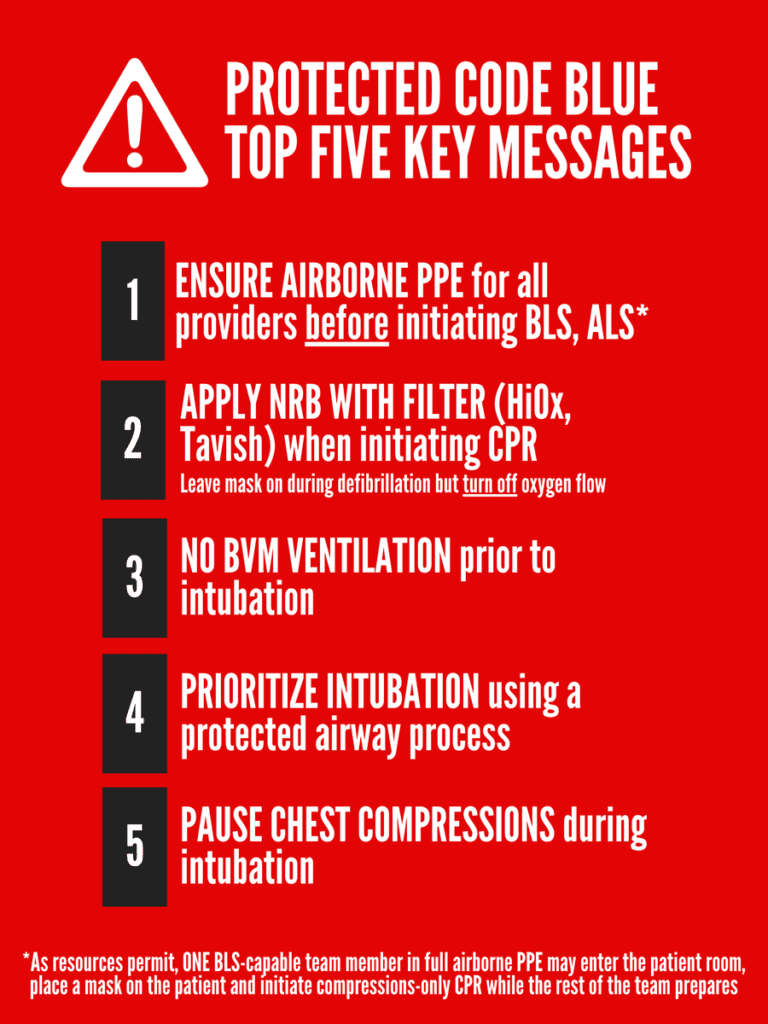

Cardiac Arrest Protocol from COVID Critical Care Website

Protected Code Blue strategy based on available personnel in PPE

In PPE Action

0 No ALS/BLS

1 HiOx mask on patient, compression-only CPR

2 As above, work to obtain IV access

3. As above, add airway operator

>= 4: Add leader— Christopher Hicks (@HumanFact0rz) March 24, 2020

Protected Code Blue Key Principles via Chris Hicks, MD

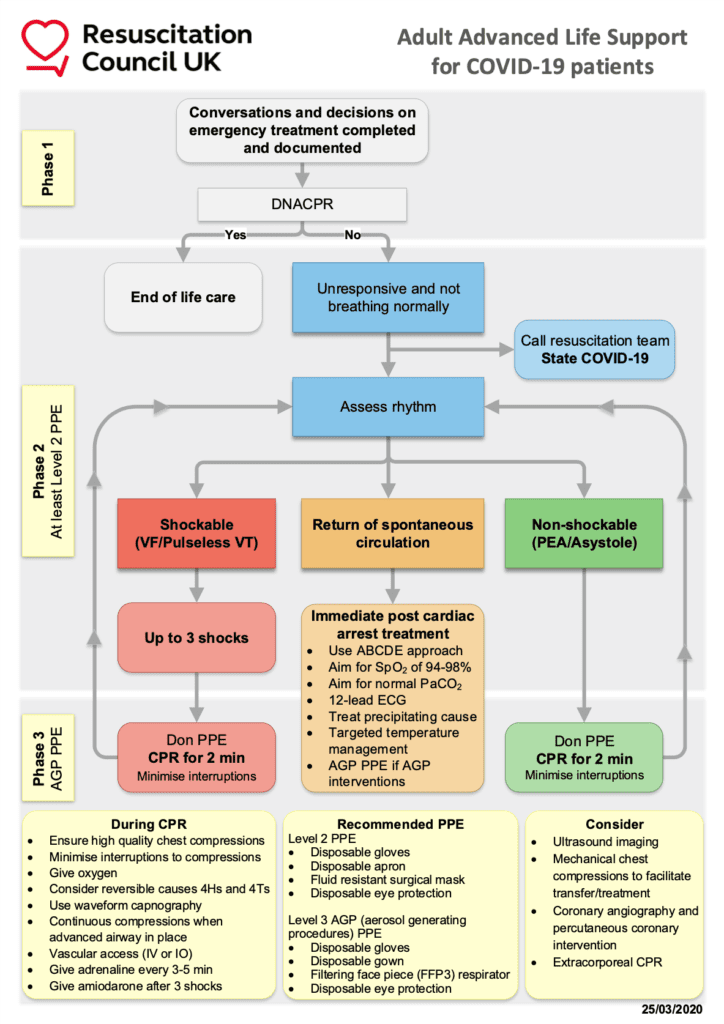

UK Resuscitation Council Adult Advanced Life Support for COVID-19 Patients [Link is HERE]

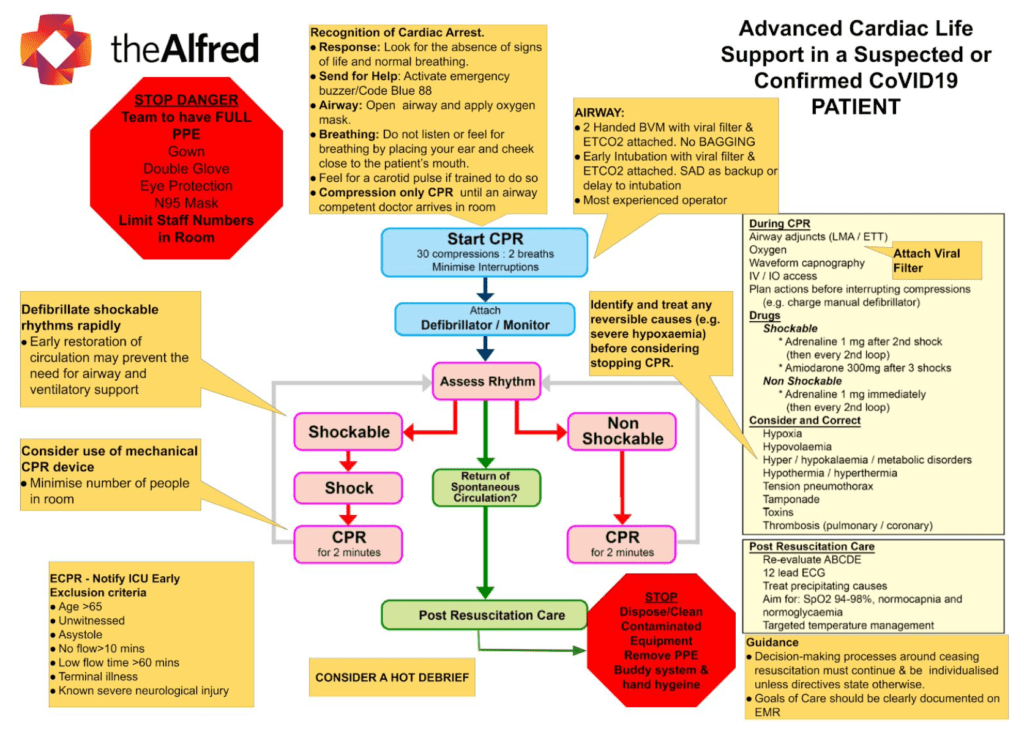

The Alfred Advanced Cardiac Life Support Recommendations for ALL Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic [Link is HERE]

References:

- Driggin E et al. Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic JACC 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Arentz M et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Shi S et al. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Welt FGP et al. Catheterization Laboratory Considerations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: From ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. JACC 2020 [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Fox SE et al. Pulmonary and Cardiac Pathology in COVID-19: The First Autopsy Series from New Orleans. Chemrxiv Pre-Print 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Shao F et al. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Outcomes Among Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Resuscitation 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Mahmud E et al. Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JACC 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- REBELEM: COVID-19 – The Novel Coronavirus 2019

- EM Cases: Cardiovascular Emergencies During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- St. Emlyn’s: COVID-19 and the Heart

- emDocs: Managing the Patient with AMI and COVID-19 – JACC Consensus Statement

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Mizuho Morrison, DO (Twitter: mizuhomorrison)

The post COVID-19: Cardiovascular Considerations appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.