Background: North America’s current opioid crisis, much of it iatrogenic (2), has led to significant increases in ED visits associated with opioids (3). These patients often present after poisoning, in withdrawal, or with other health issues associated with their disease.

Background: North America’s current opioid crisis, much of it iatrogenic (2), has led to significant increases in ED visits associated with opioids (3). These patients often present after poisoning, in withdrawal, or with other health issues associated with their disease.

It is well accepted that Opioid Replacement Therapy (ORT), namely, methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone, are successful harm reduction agents shown to improve health and social outcomes (4). Several individual providers, and even large academic institutions, have started initiating ORT, specifically buprenorphine/naloxone, in the ED when dependent patients present in withdrawal.

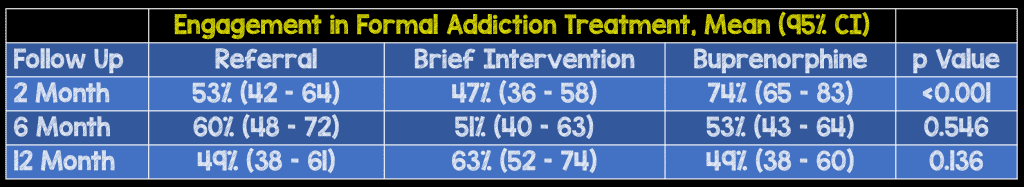

D’Onofrio et al., in 2015, published outcomes after 30-days from a clinical trial of patients who met criteria for opioid dependence in the ED that were randomized to one of three interventions: referral, brief intervention or ED-initiated buprenorphine followed by 10 weeks of continued buprenorphine treatment in a primary care setting (5). They found that patients receiving ED initiated buprenorphine with continuation in primary care were more likely to be engaged in formal addiction treatment at 30 days (p < 0.001). More recently, they have published follow-up outcomes on a subset from the original study at 2, 6 and 12 months.

Article:

D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Busch SH, Owens PH, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence with Continuation in Primary Care: Outcomes During and After Intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(6):660-666. PMID: 28194688.

What They Did

- Clinical Question: Is ED-initiated buprenorphine-naloxone with follow-up in primary care more effective at 2,6 and 12 months at: Promoting engagement in treatment for dependence; deterring illicit drug use, and reducing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk behaviors when compared to treatment referral only, or a brief intervention with referral to treatment?

- Population: Patients were recruited from the ED in a large urban teaching hospital between April 7, 2009, and June 25, 2013 into a randomized controlled trial with results to above question at 30 days published in 2015 (5).

Exclusion criteria:

- under 18 years of age

- not English speaking

- difficulty communicating due to dementia or psychosis

- any medical or psychiatric condition requiring hospitalization

- suicidal

- in police custody

- enrolled in formal addiction treatment

- requiring prescription opioid medication for a pain condition

Inclusion criteria:

- Urine sample positive for opioids

- Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) score of 3 or higher

- Attended at least one study follow-up assessment at either 2, 6 or 12 months (this is where the population differs from the original RCT population)

- Eligible patients were screened, when research associates were present in the ED, using a general health quiz with questions on prescription opioid and heroin use embedded in a 20-item health questionnaire.

Interventions:

- Referral (Arm 1): Handout provided to patients listing names, locations and phone numbers of addiction treatment services (e.g., inpatient and outpatient opioid treatment programs, office-based providers of buprenorphine/naloxone).

- Brief Intervention (Arm 2): A Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI) (ref), modified for opioid dependence, was performed. A variety of addiction treatment options were then discussed and research assistants then directly linked the patient with the service including reviewing the patient’s eligibility, obtaining insurance clearance and arranging transportation.

- Buprenorphine/naloxone (Arm 3): A BNI plus buprenorphine/naloxone was initiated. Appropriate take-home doses were provided until a scheduled appointment in the hospital’s primary care center within 72 hours.

Outcomes:

- Primary: Engagement in formal addiction treatment evaluated at each follow-up by self-report using the Treatment Services Review (ref).

- Secondary: Illicit opioid use in the past 7 days using the timeline follow back assessment; rates of opioid-negative urine test results (only at 2 and 6 months); and HIV risk using an 11-item validated scale for HIV risk-taking related to drug use and sexual behavior

Results:

- The total study sample represented 88% of the patients enrolled in the original trial (5). This subset was comparable to the randomized sample on all evaluated characteristics.

- 33% of patients were seeking treatment for opioid dependence at the index visit, 9% presented with an overdose, and the remaining 58% were identified through screening.

- At 2 months, the buprenorphine/naloxone group reported significantly less illicit opioid use, with 1.1 (95% CI 0.7–1.5) days of illicit opioid use in the past 7 days, compared with 1.8 (95% CI 2–2.4) in the referral group and 2.0 (95% CI 1.4–2.6) in the brief intervention group (p = 0.040). However, similarly no difference at the later follow-up points.

- There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups regarding HIV risk behaviors or urine toxicology tests at any of the assessment points.

Strengths:

- Asks a clinically important question in a marginalized, at risk group

- Employed a robust randomized controlled trial design taking into consideration many confounding variables in the analysis

- First study looking at medium-term follow up outcomes of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment

- They present an all too rare, but logical model of care, where emergency departments and family medicine clinics within the same institution work together to ensure proper follow-up of addiction presenting for the first time to the ED

Limitations:

- Small sample size with significant losses to follow-up

- Positive urine sample inclusion criteria is fairly restrictive as some opioids would have been missed

- Selection bias of patients recruited based on time when RAs were in the ED

- Engagement in formal addiction treatment at 2, 6 and 12 months are based on self-report and were not confirmed with treatment providers

Discussion:

Opioid-dependent patients who received ED-initiated buprenorphine with continuation in primary care were more likely to be engaged in treatment and reported less use of illicit opioids at the time of follow-up assessments at 2 months. The 2-month assessment occurred while patients were still receiving buprenorphine through primary care, as the study treatment was provided for a total of 10-weeks patients in the buprenorphine group were transitioned to other treatment providers or tapered off buprenorphine after 10 weeks.

Although likely regarded as a weakness, it is also evidence in itself. These differences in outcomes did not persist at the 6- and 12- month follow-up which, unsurprisingly suggests that close follow-up is essential and the massive lack of buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone prescribers is likely a larger barrier than the effectiveness of the intervention itself.

Author Conclusion: “ED-initiated buprenorphine was associated with increased engagement in addiction treatment and reduced illicit opioid use during the 2-month interval when buprenorphine was continued in primary care. Outcomes at 6 and 12 months were comparable across all groups.”

Clinical Take Home Point:

In this study, for 27% of the enrolled ED patients, the index ED visit represented their first contact with the healthcare system for their dependence. Thus, unsurprisingly, the ED visit is a massive opportunity to engage patients, who often avoid healthcare professionals, with opioid use disorder in effective medication-assisted and psychosocial treatment.

These results should, in the setting of this unabated crisis, interpreted with caution. It is important to note that the significant result at 2-months was by construction as patients received care until 10 weeks as part of the study. Lack of proper follow-up in primary care by physicians providing non-judgmental addiction care with ORT as a possible tool is all too rare.

Guest Post

Jonathan Gravel

Epidemiologist and Resident Physician at the University of Toronto

CanadiEM Junior Editor

Twitter: @gravel_jon

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- Emergency Medicine Ottawa: Are You Afraid of the Dark? Suboxone and Methadone in the ED

- Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians: Using Buprenorphine to Treat Acute Opioid Withdrawal in the ED

References:

- Kinsella K, Baraff LJ. Initiation of therapy for asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009; 54(6):791-2. PMID: 19942065

- Goozner M. The iatrogenic roots of the opioid epidemic. Mod Healthc. 2016; 46(7):26. PMID: 27078923

- Jones CM, McAninch JK. Emergency Department Visits and Overdose Deaths from Combined Use of Opioids and Benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015; 49(4):493-501. PMID: 26143953

- Whelan PJ, Kimberley R. Buprenorphine vs methadone treatment: A review of evidence in both developed and developing worlds. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012; 3(1): 45-50. PMCID: PMC3271614

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015; 313(16):1636-44. PMID: 25919527

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim Rezaie (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Do Patients with Opioid Dependence Benefit from Buprenorphine/Naloxone Treatment Initiation in the Emergency Department? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.