Background: Epinephrine remains a staple in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). However, the optimal dose, timing, and route of administration are still unknown. Standard dosing of epinephrine is 1mg every 3 to 5 minutes via the intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) route. IO lines are quicker to establish and have a higher first-attempt success rate compared to IV access. Rapid placement and ease of use minimizes delays for critical patients requiring quick access. The literature, although methodologically limited, is mixed about the use of IV vs IO access for epinephrine in OHCA.

Background: Epinephrine remains a staple in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). However, the optimal dose, timing, and route of administration are still unknown. Standard dosing of epinephrine is 1mg every 3 to 5 minutes via the intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) route. IO lines are quicker to establish and have a higher first-attempt success rate compared to IV access. Rapid placement and ease of use minimizes delays for critical patients requiring quick access. The literature, although methodologically limited, is mixed about the use of IV vs IO access for epinephrine in OHCA.

Paper: Zhang Y et al. Intravenous Versus Intraosseous Adrenaline Administration in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Resuscitation 2020. PMID: 31982506

Clinical Question: Do IV or IO routes lead to different outcomes in patients with OHCA who received pre-hospital epinephrine?

What They Did:

- Retrospective, observational analysis of adult patients with OHCA of presumed cardiac origin who had EMS CPR, received epinephrine, and enrolled in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) Cardiac Registry between 2011 and 2015

- Patients were not randomized but divided into IV and IO groups based on administration route of epinephrine

- Performed logistic regression analysis (a fancy way to account for confounding variables) to evaluate the association between adrenaline delivery routes and prehospital ROSC, survival to hospital discharge, and favorable neurologic outcome. They also performed propensity score matching to account for selection bias.

Outcomes:

- Primary: Survival to hospital discharge

-

Secondary:

- Prehospital ROSC

- Favorable neurological outcome at hospital discharge (mRS ≤3)

Inclusion:

- Adult patients ≥18 years of age

- OHCA

- Received EMS treatment

- Enrolled in the ROC Cardiac Registry

Exclusion:

- ≥89 years of age

- DNR orders

- Arrest from an obvious cause (i.e. anaphylaxis, chemical poisoning, drowning, drug poisoning, electrocution, excessive cold, excessive heat, foreign body obstruction, hanging, lightning, mechanical suffocation, non-traumatic exsanguination, radiation exposure, respiratory, SIDS, smoke inhalation, strangulation, terminal illness, trauma, venomous stings, etc…)

- Unclear outcome status

- Did not receive epinephrine

- Epinephrine administration route was unclear

- Received adrenaline via endotracheal route, pre-existing IV route, or more than one administration route

- Failed administration attempts of epinephrine through another route

Results:

- 35,733 patients included

- IV Epi: 27,733 patients (77.7%)

- IO Epi: 7,975 patients (22.3%)

- Overall Outcome Rates:

- Prehospital ROSC = 5.2%

- Survived to Hospital Discharge = 3.7%

- Favorable Neurological Outcome at Hospital Discharge = 3.7%

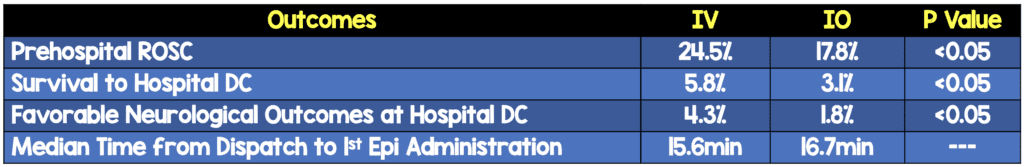

- All outcomes favored IV route over IO route:

- Survival to Hospital DC (Primary Outcome): aOR 1.468 (95% CI 1.264 – 1.705)

- Prehospital ROSC: aOR 1.367 (95% CI 1.276 – 1.464)

- Favorable Neurologic Function: aOR 1.849 (95% CI1.526 – 2.250)

- The results remained statistically significant after propensity matching

Strengths:

- Data is drawn from a large dataset developed by the North American ROC research program and clinical sites which all adhere to current guidelines

- This was a consecutive set of patients as opposed to a convenience sample

- Route of vascular access was objectively defined to remove confounding access site variables including using no more than one route that was the initial and sole option used

- Patients who had mixed method of administration (ie had IO and IV in place or had ETT administration) were excluded

- Accounted for confounders such as age, witnessed status, bystander CPR, public location, EMS response interval, initial rhythm, cumulative adrenaline dosage, compression rate, and use of an advanced airway device

- Because patients were not randomly assigned to IV or IO groups, a propensity score matching was used to address the influence of selection bias

Limitations:

- Retrospective observational study can only show association not causation as there may be other confounders not accounted for

- Compression rate was defined as the average rate of the first five minutes of EMS CPR from monitor-defibrillator recordings, but we have no idea what the rates were after this as they were not reported

- Other factors that are known to be optimal in compressions were not reported including: chest compression depth, chest compression fraction, chest compression release, or chest compression interruptions

- Majority of patients included were non-shockable rhythms which have a worse prognosis than patients with shockable rhythms

- Location of the IOs was not described. A humeral IO is far different than a tibial IO in a low flow state and also has the potential to confound these results

- There are patient-specific factors that we do not know that could affect these results. For example, if a patient is chronically ill, with poor potential for venous access, and they are less likely to survive, then they are more likely to get IO access which could falsely lower the outcome rates in this group

Discussion:

- Some important numbers and times to mention about this study overall:

- EMS witnessed cardiac arrest was only 9.3%

- Bystander CPR performed was 43.8%

- EMS response interval was 5.1min

- Initial EMS-recorded rhythm was 22.2% shockable and 77.8% non-shockable

- Cumulative adrenaline dose 3.0mg

- Time form dispatch to 1st adrenaline dose was 16.4min

- Compression rate at first 5min was 108

- Advanced airway placement 2% of patients

- Important confounders that would favor IV over IO:

- Bystander witnessed cardiac arrest (IV 40.0% vs IO 34.6%)

- Public location (IV 15.4% vs IO 11.4%)

- Shockable Rhythm (IV 24.0% vs IO 16.1%)

- This appears to demonstrate that the IO group was simply sicker and, this study is not an indictment of IOs as much as an investigation of sicker and less sick cardiac arrest patients (yes, such a thing exists as “less sick cardiac arrest.”)

- In North America the majority of IO access is established in the lower limbs and the majority of IV access is established in the upper limbs, thus making this an apples to oranges comparison. What would have been a far better comparison would be humeral IO vs upper limb IV access.

- Prior high-quality studies (ie PARAMEDIC) have demonstrated that epinephrine does not improve meaningful outcomes in cardiac arrest (REBEL EM Review). Thus, the route of administration of a medication that hasn’t been shown to improve meaningful outcomes shouldn’t matter.

Author Conclusion: “Compared with the IO approach, the IV approach appears to be the optimal route for adrenaline administration in advanced life support for OHCA during prehospital resuscitation.”

Clinical Take Home Point: This study should not change your practice of IV vs IO access in OHCA. Future randomized trials of access are needed to clarify this situation. If you are using IO access in cardiac arrest you want to go as proximal to the central circulation as possible, which is most commonly the humeral IO.

References:

- Zhang Y et al. Intravenous Versus Intraosseous Adrenaline Administration in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Resuscitation 2020. PMID: 31982506

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- JournalFeed: Point Counterpoint – IV Beats IO Epinephrine for OHCA

- JournalFeed: IV or IO Antiarrhythmics for OHCA?

- JournalFeed: Vascular Access in a Code – IO or IV?

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post IV or IO Epi in OHCA? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.