Hey there REBEL Cast listeners, Salim Rezaie here. For me and I am sure many COVID-19 has been quite the whirlwind. So much information, so little time to process all of it. Meanwhile, many of us are on the frontlines having to take care of these patients. Personally, I have never been so wrong, so many times about a single disease process. What I say today, may be different tomorrow. This podcast was recorded on April 3rd, 2020 so any information that comes out after this, might change the viewpoints that are expressed today.

Hey there REBEL Cast listeners, Salim Rezaie here. For me and I am sure many COVID-19 has been quite the whirlwind. So much information, so little time to process all of it. Meanwhile, many of us are on the frontlines having to take care of these patients. Personally, I have never been so wrong, so many times about a single disease process. What I say today, may be different tomorrow. This podcast was recorded on April 3rd, 2020 so any information that comes out after this, might change the viewpoints that are expressed today.

REBEL Cast Episode 79 – COVID-19 – Trying Not to Intubate Early & Why ARDSnet may be the Wrong Ventilator Paradigm

Click here for Direct Download of Podcast

Special Guests:

David A. Farcy MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FCCM

President of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine

Director, Emergency Medicine Critical Care

Mount Sinai Medical Center

Miami Beach, FL

Twitter: @DFarcy

Evie Marcolini, MD, FAAEM, FACEP, FCCM

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Neurocritical Care

Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire

Board of Directors, American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Twitter: @EvieMarcolini

Cameron Kyle-Sidell, MD

Critical Care Medicine

Emergency Medicine

Maimonides Medical Center

Brooklyn, NY

Twitter: @cameronks

Ronald O Perelman Department of Emergency Medicine

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bp5RMutCNoI[/embedyt]

This podcast is longer than we typically do on REBEL Cast (1hr 30min), however there is lots of information that is critical in the treatment of COVID-19 patients with pneumonia. The questions we tackled were as follows:

- Many of us have been working under the paradigm that COVID-19 PNA eventually develops into ARDS in the sickest patients. It appears to me that these patients don’t fit into this paradigm. Many have normal to high compliance and there are certainly reports of patients not showing any signs of distress. What are you seeing clinically?

@EMNerd_ @emupdates @CriticalCareNow @ThinkingCC @srrezaie @Turtle1doc @PulmCrit STOP INTUBATING COVID PATIENTS FOR HYPOXEMIA!!! This is a tracing of a cirrhotic w COVID. Sat does not reflect organ arterial tissue saturation. They do not get tachycardic pic.twitter.com/vSwWkaCeY8

— Cameron Kyle-Sidell, MD (@cameronks) March 27, 2020

-

- In New York:

- Intubation is a primary intervention

- We know intubated patients have a mortality rate between 50-80%

- Initially, some patients are not displaying respiratory distress which makes calling this ARDS confusing

- Patients are neither living nor dying from respiratory fatigue, rather a pure hypoxemic condition

- The lungs we see in a high compliance state do not display any characteristics resembling ARDS right after being placed on a vent

In New Hamphsire:

- Not in surge yet, but preparing and using simulations

- Currently waiting longer to intubate patients such as those with sats near 70% while utilizing other techniques such as high-flow nasal cannula

- In the beginning, we discussed intubating early for patients, but also to protect the clinicians as you are at the highest risk for aerosolization

- If we can stave off ventilation such as using high flow nasal cannula, awake proning, or even CPAP, patients will spend less time on the ventilator

In Miami:

- The dogma where we look at a patient and see they are hypoxic, or they will tire out and we need to intubate early

- If not intubated early, there will be a crash intubation, however we have not seen this

- We have a similar experience to New York: not resembling ARDS

- I was arguing with a patient who’s O2 sats were low because he was refusing intubation. As an ER physician I felt he did not have the mental capacity to sign out AMA because he was hypoxic, however, he was making more sense than I was and was not in distress.

- A fear with non-invasive ventilation and highflow nasal cannula is aerosolization as this is a real risk

- Anyone who is dealing with these patients should be in full PPE

- Risk should be minimal if we are using these strategies

- In New York:

-

One of the big fears with using NIV/HFNC is aerosolization. This is a real risk, but for many we are in full PPE which should make this risk minimal. What are your thoughts on NIV/HFNC as an intermediary step for some patients in terms of staff safety and the patients in front of us?

- My initial deterrence toward intubation is an ARDSnet strict protocol for a high compliance disease

- However, patients are not going into respiratory fatigue, they simply get extremely hypoxemic and bradycardic and they die

- This does not appear to be a death by ARDS and seems out of the ordinary

- Need to develop a more successful ventilator strategy that would better fit the disease

- Possibly turn it into a CPAP machine to simulate high flow

- You do not want to put someone on a ventilator who can survive without it, but you also do not want to not put someone on a ventilator who will not survive without it

- We have seen multiple patients in different groups

- A patient satting 61% room air with a heart rate of 135, and tachypneic. He was talking and sitting up, signing consent to let us take pictures. We proned him and started high-flow. 2 hours later, his sats were in the 90s

- Take time to see your patient

- The fear of contamination makes it that we cannot treat people as well as we want to

- When we work in the ER and ICU we are exposed to patients with covid, however when we walk into a hospital and open the door, we could be walking into it as well

- There are a few trials where there is a reduction of aerosol when you use a mask over the patients face

- It has been a struggle as appropriate PPE is difficult to come by

- When you wear the same PPE for 14 hours, is it actually PPE? This is the state of how things are in New York City.

- A lot of us associated this with HAPE syndrome (high-altitude pulmonary edema)

- Looking at HAPE the mechanism is really hydrostatic pulmonary edema caused by hypoxemia

- At high altitude, the pulmonary artery pressure increases because of alveolar hypoxia which leads to arterial vasoconstriction that is patchy and not homogenous

- Comparing a HAPE chest x-ray to covid, it appears similar.

- One of my attendings who actually suffered HAPE in Aspen said he was walking around, talking, with a heart rate of 130 and an O2 sat of 39%

- In my reading of available evidence, patients with COVID-19 PNA who get intubated have a mortality rate of anywhere from 50 – 90%. Many studies reporting in the 80% range. This is not a causation of intubation and mechanical ventilation but an association as most of these reports are observational and retrospective. In other words, maybe the patients were just so sick they were going to have a high mortality anyways. On the flip side this higher mortality may also be the fact that we are intubating patients early and using the ARDSnet protocol. What are you currently using to manage patients on the ventilator?

-

- Typically in ARDS whether its infiltrate, fluid, or proteinaceous material usually the lungs are getting thicker, harder to move air into it which is creating fatigue

- Is it possible, rather than the lungs becoming “thicker”, are they actually getting thinner?

- Is it possible we have a disease with a higher compliance than normal, in which case is it possible that the PEEP we are using in order to get the sats that we want is causing lung injury?

- I have seen palliative care patients who pass in that fashion without respiratory distress and without hypotension and yet could it be possible that what we are trying to do with our primary intervention by trying to get their sats to a certain level we typically see as functional, we are using pressure that is causing severe lung injury?

- Even if true, we may have to cause lung injury to help people survive

- There is speculation of 2 different phases: a high compliance that goes into a low compliance where there is a transition

- What I suggest is to separate the patients between high and low compliance and figure out different respiratory strategies for each

- For a covid patient with high compliance, leave their FiO2 at 100% until the viral replication has stopped and provide only enough PEEP to achieve a sat of 80%

- Provide either narcotics or sedatives to keep their respiratory rate under 20

- If unable to achieve this or if there is any dyssynchrony you can then possibly paralyze

- The paradigm is difficult because it goes against everything we’ve done and what we believe when we choose to not intubate despite the patient’s sats

- Give the patient a chance, and try not to put every single patient into a “box”

- In ER medicine we tend to try to make people “fit”. We have to titrate and take things slow, maybe try to customize care

- The patient will teach us about the disease, but we have to really listen and watch to see how he responds to treatments

- 1 or 2 wks from now, if we find that what we’re doing is not working, we may be able to pivot

- Some hospitals setting up protocols such as

- Covid positive on CT or exam

- Saturating less than 90% on 6 L nasal cannula

- Early intubation followed by ARDSnet strategy

- It is possible that this is referring to what may be hundreds of thousands of people, which is concerning

-

Study out of NYC [6]

- Cross-sectional analysis of patients with COVID-19

- Hospitalized: 1,999 (48.7%)

- Predictors of Hospitalization: Age >65years, BMI >40, Hx of Heart Failure

- Predictors of Critical Illness: Admit O2 <88%, D-dimer >2500ng/mL, CRP > 200mg/L

- Hospitalized: 1,999 (48.7%)

- Outcomes:

- Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: 445/1999 (22.6%)

- Extubated: 38/445 (8.5%)

- Still Intubated: 245/445 (55%)

- Death or Hospice: 292/1999 (14.6%)

- As many patients still hospitalized, numbers above may be underestimation

- Cross-sectional analysis of patients with COVID-19

- Typically in ARDS whether its infiltrate, fluid, or proteinaceous material usually the lungs are getting thicker, harder to move air into it which is creating fatigue

-

In my mind patients present into one of 4 clinical categories and I want to go over these one at a time…

-

Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 with minimal symptoms. These patients can most likely go home, but one big concern is how do we follow them up. What are you using to decide who can go home and who can’t? How are you following them up?

- In New Hampshire:

- If the patient is good enough to walk and talk and is not symptomatic, will discharge home with preprinted set of instructions that ask them to quarantine

- Have a system in place where PAs will follow-up on the tests and call the patient with results.

- In Miami:

- If a patient is satting at 100%, we stress them

- If they are able to do 3 mins of walking (sitting/standing for elderly) and their O2 sat remains above 96% we swab them and send them home

- If their sats drop below 96%, then they have imaging and we quantify them based on what kind of therapy we will send them home with

- If a patient comes in hypoxic, they go directly to the back for treatment and testing

- If we send home a patient with O2 sats in the 90s, they are given a prescription for an oxygen compressor and we try to have case management organize them for delivery

- If a patient is satting at 100%, we stress them

- In New York:

- We have faced more obstacles with regards to sending people home as the ED has essentially turned into a full covid unit

- The threshold for sending people home has gone down, because our hospitals are simply more full

- There is a possibility that many of these people that we send home will come back which I don’t feel there is any way to prevent

- There are all sorts of discharge issues. Possibly the largest concern are those that have no supervision, live by themselves, especially if they are older or are obese.

- I do not think that someone that we send home and returns should be seen as a failure, but rather organizing their ability to return should be seen as a success.

- In New Hampshire:

-

Suspected or confirmed COVID-19 with minimal symptoms. These patients can most likely go home, but one big concern is how do we follow them up. What are you using to decide who can go home and who can’t? How are you following them up?

-

- Silent Hypoxemia (“Happy Hypoxemia”): These patients often have low O2 sats but have no external signs of respiratory distress, AMS, or lack of perfusion. In my mind these patients are prime candidates for NIV/HFNC and awake proning. Are any of you using awake proning? Any logistical issues with this?

-

-

- Ideally, all these patients should have as much oxygen as possible

- At some point, hypoxemia worsens hypoxemia and these are the perfect patients to put on high flow

- In New York, we are at a point where we need to ensure our oxygen supply is okay because high flow uses a tremendous amount of oxygen, more than a ventilator

- Perhaps high flow may even be more gentle than CPAP.

- The patients sent to the floor on high flow will become entirely dependent on oxygen if you take them far enough such as on 80% and 50L

- A patient in the ED on high-flow kept insisting on going home. I informed him if the system falls off his face, he will die.

- My reservation with CPAP is it is not something people can keep on for 3-4 days

- As far as proning, you will typically see a remarkably improved O2 saturation as well as blood gas

- If someone is saturating in their 60s and you prone them and they are now 92, this recruitment does not appear to be sustained unless the viral replication slows down.

- A higher change is observed when on their side; this is true with obese patients as well

-

First draft of a PROPOSED pathway for identify 'happy hypoxic' #COVID19 patients at triage, and giving them a chance NOT to get intubated. Work in progress. Very interested to hear from anyone with something similar/better in place. No experience of these patients yet pic.twitter.com/gFp5JsMd6V

— Cliff Reid (@cliffreid) April 7, 2020

-

- Intermediate Hypoxemia: These patients often have low O2 sats but have some mild symptoms of respiratory distress such as tachypnea and tachycardia. These patients may require intubation but may also benefit from NIV/HFNC + Awake proning. What is your threshold to consider intubation?

-

-

- Largely dependent on the patient and the environment

- Initially if the patient required high-flow at 80% 50L to achieve a sat of 88-90%, this was the time for intubation

- However our next patient had no distress. We did everything we could to not intubate which let us know even more this disease is nothing like we have dealt with before

- As a guide, we try to get patients on high-flow and do not send them to the floors anymore

- If the patient requires FiO2 of 90% high flow to achieve a sat of 88-90 and you are in distress which is predominately tachypnea and anxiety, then it is time to intubate

- We are limiting the amount of people going into the room as well such as attending and resident, no RT or nurse

- New Hampshire has not had a surge: we have time, ventilators, and negative pressure rooms with resources

- Will probably have a lower threshold because that is what we are comfortable with and we have the resources

- Still simulating throughout the day to make sure it is safe for the patient and for us so we will probably intubate earlier

-

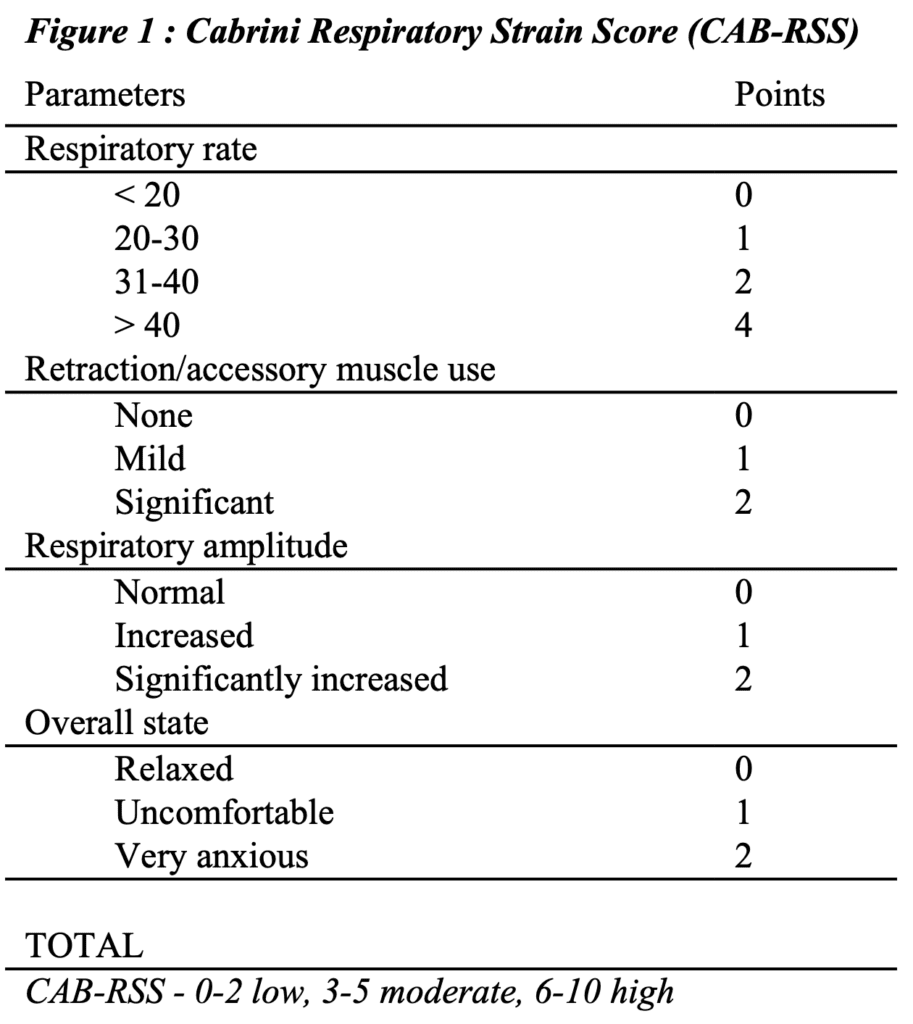

Addendum (04/25/2020): Cabrini Respiratory Strain Score (CAB-RSS) [Link is HERE]

- Not yet validated, but can be used as a marker of severity and potentially a decision tool for progressing to a higher level of ventilatory support

-

-

- Respiratory Distress: These patients require intubation and are too far gone in my opinion to test NIV/HFNC. Many of these patients will have high pulmonary compliance with hypoxic vasoconstriction in the lungs. It seems increasing PEEP and prone positioning may be of minimal help with recruitment of collapsed lungs (i.e ARDSnet). High PEEP (>15cmH20) may also compromise cardiac filling. What ventilation strategies do you recommend in these patients with the limited information we have thus far?

-

- ARDSnet trial discusses starting at low tidal volume 4-6 mL/kg

- Titrating PEEP to maintain FiO2 above 90 with PEEPs as high as 18-20cmH20

- Recommend not bagging patients: take them directly off high flow to intubation If they drop from 60s down to the 40s, you have 30 seconds to intubate

- Right after intubating in the ED, they will be in a high compliant state and are tolerating volume and do not have the damage that happens with ARDS

- Start the patient with 8-10 cc/kg of tidal volume (ideal body weight) based on mean airway pressures and plateau pressures to evaluate compliance

- Put on 100% O2, start PEEP at 5

- You will have to tolerate a lower sat because after intubating, the sats will drop, however they will go up slowly

- Maintain a PEEP 8-10cmH20 and lower if possible

- Use an oxygen first, pressure last strategy

- Know there is a possibility that with each increasing pressure, you risk damaging some lung

- If you need better sats, be more liberable with the tidal volumes

- If the patient is hypotensive, try to decrease the PEEP if you can

- I do not feel there is a way to achieve sats above 92% in this hypoxemic, progressive disease by increasing the PEEP

-

Evie I would like to ask you a few questions specifically in regard to neurological concerns:

- How are you handling patients with stroke symptoms and suspected COVID-19. Imaging, systemic thrombolysis, endovascular therapy?

-

-

- We are not doing anything different except that we are donning PPE

- Patients are screened appropriately and we move forward

- There is some emerging data from Italy and China that covid-19 patients have a blood clotting disorder that may be contributing to their respiratory failure

- Microthrombi possibly forming in the vessels of the lungs

- Patients may have inflammation-linked tissue damage that contribute to clot formation

- Maybe tPA would help?

- We are not doing anything different except that we are donning PPE

-

There appear to be lots of reports of headache and AMS as a common symptom. I am unaware of CSF studies to date, but should we be concerned about encephalitis? Do these patients need LPs? Do we have any idea about the mechanism or prognosis of these patients?

- We know from previous coronavirus, there are a couple of different ways the virus can get into the nervous system

- Dissemination from systemic circulation, which makes sense

- Moving across the cribriform plate of the ethmoid.

- What is the mechanism?

- The virus and previous viruses latch on to ACE2 receptors

- When the coronavirus latches, that is how we might see symptoms

- You can get retrograde axonal transport in the olfactory, trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, the vagus or even peripheral nerves

- We know from previous coronavirus, there are a couple of different ways the virus can get into the nervous system

-

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTGpWDIzEPQ[/embedyt]

Thinking Critical Care Webinar – COVID-19 Respiratory Management – A Physiological Approach (Video Time: 1:34:28)

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c7s3fS6RTlQ[/embedyt]

Critical Care Management via JAMA Network with Derek Angus (Video Time: 47:50)

References:

- ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012. PMID: 22797452

- Grasso S et al. ARDSnet Ventilatory Protocol and Alveolar Hyperinflation: Role of Positive End-Expiratory Pressure. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2007. PMID: 17656676

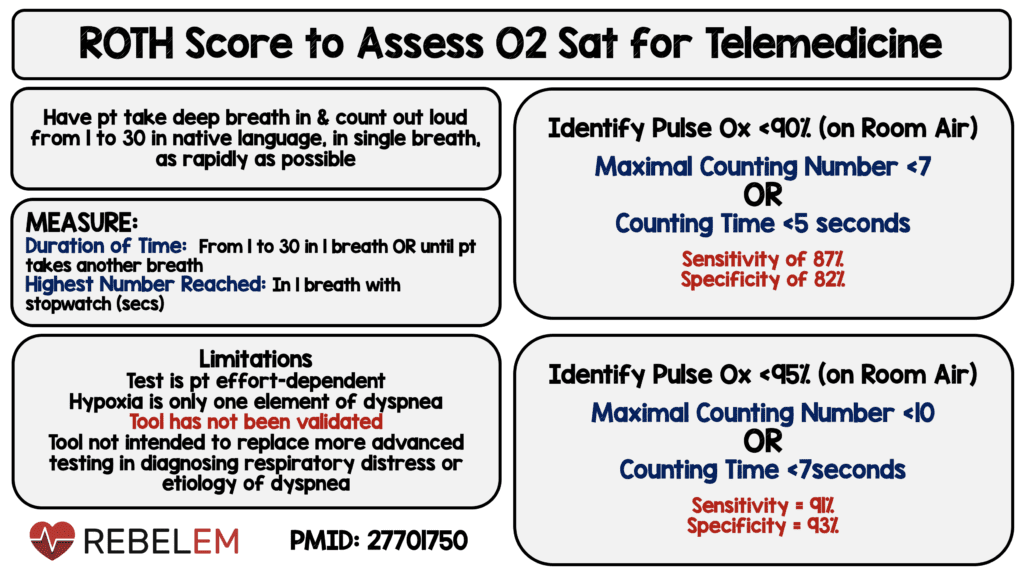

- Chorin E et al. Assessment of Respiratory Distress by the Roth Score. Clin Cardiol 2016. PMID: 27701750

- Gattinoni L. Preliminary Observations on the Ventilatory Management of ICU COVID-19 Patients. SFAR 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Gattinoni L et al. COVID-19 Does not Lead to a “Typical” Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. ATS 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Petrilli CM et al. Factors Associated with Hospitalization and Critical Illness Among 4,103 Patients with COVID-19 Disease in New York City. MedRxiv Preprint 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Gattinoni L et al. COVID-19 Pneumonia: ARDS or Not? Critical Care 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- REBELEM: COVID-19 Hypoxemia – A Better and Still Safe Way

- EMCrit: Webinar I Gave to Pulm/Crit Care Fellows on Avoiding Intubation and Initial Ventilation of COVID19 Patients

- EM Updates: 3 Weeks of Coronavirus in New York City

- FOAMCast: Is it ARDS? HAPE? Hemoglobinopathy?

- Thinking Critical Care: COVID-19 Webinar – Respiratory Management

- FOAMCast: COVID-19 – New York Outcomes

- PulmCrit: Understanding Happy Hypoxemia Physiology

- FOAMCast: The Paradigm Shift From Early Intubation

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post REBEL Cast Ep79: COVID-19 – Trying Not to Intubate Early & Why ARDSnet may be the Wrong Ventilator Paradigm appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.