INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

You’re moonlighting in a remote access hospital. EMS radios in for a burn patient and to anticipate a difficult airway. You can hear the tension in their voice. They’re rolling up now.

The patient is horribly burned. She was smoking with her home O2 on and has severe mixed partial and full thickness burns to the chest, neck, face, and airway. You attempt to intubate, but the glottis is edematous and closing. You see the need for the inevitable – you’re going to have to perform a cricothyrotomy. She is morbidly obese. Her oxygen saturation is tenuous on BVM. You are unfamiliar with your team. And to make matters worse you haven’t practiced or even mentally rehearsed a cric in years.

Emergency Medicine (EM) is an amazing specialty because anything can come through the door at any moment. This same reality makes practicing EM incredibly challenging and at times downright terrifying. This is no more true than in the performance of HALO (high acuity, low occurrence) procedures. Given their rarity, these procedures and the clinicians who perform them are often at risk for skillset decay. Combating this decay simply cannot happen through standard clinical practice. To put it simply, you need a plan on how you are going to stay sharp and avoid becoming obsolete.

SMART OBJECTIVES

By the end of the post learners will be able to:

- Draw an experience curve and define the learning and forgetting segments.

- List the elements of high-quality procedural practice.

- Craft a schedule for personal use of HALO procedural practice.

HOW DID WE GET HERE? LEARNING AND FORGETTING CURVES

Learning Curves

Learning curves represent the relationship between units of practices and level of performance. They have been studied in depth across many aspects of medicine, including procedural skills. They all have the typical “S shaped” curves seen in Figure 1 below. At first learning is hard and little progress is made. Then you have your “aha” moment, and you rapidly progress up the Y axis of Performance. Eventually things start to level out again and the law of diminishing returns comes into play. Much of this happens during residency, where the ACGME and your program work hard to make sure that level out occurs above the line of competence.

Forgetting Curves

But then, life carries on. You graduate. You go into practice, maybe have a family, develop a hobby, and time plays its nasty little trick on you. Your skills and competence decay with the passage of days, weeks and months. This can be plotted as a Forgetting Curve (Figure 2), the slope of which depends on many things – the quality of the teacher, if stress is included in the training, if you’re well fed, have good sleep, etc. For me, I see my Forgetting Curve in light blue- I feel like I forget almost everything, nearly immediately.

Experience Curves

If we combine the Learning and Forgetting Curves into something that more accurately represents real life, we get the Experience Curve (Figure 3). In this curve we see the initial “S shape” of the Learning Curve and the gradual decay of skill with time, the Forgetting Curve part.

With time and without intervention, our performance will inevitably fall below the threshold of competence. This is where Spaced Repetition comes into play.

A Note to the Residents out there

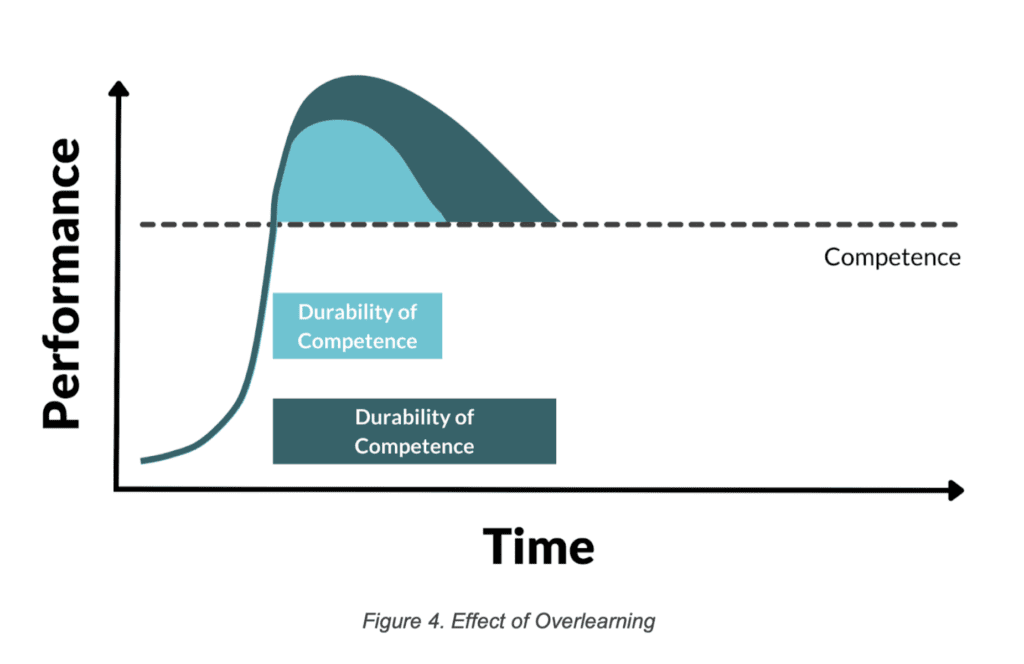

When you go through your training, there is an important concept called overlearning. This is the idea of learning something so well you bring yourself well above the line of competence.

If we look at overlearning and what that does to your competence the goal should not be “I want to place a chest tube without complications,” it should be “I want to be the Michael Jordan of chest tube placement.” By targeting mastery, a funny thing happens to our competence. As you can see in the below experience curve (Figure 4), the total amount of time spent above the competency line is greatly extended and the rate of decay is slower. So residents, don’t target good, aim for great.

HOW TO CRAFT YOUR TRAINING TO KEEP YOUR COMPETENCE

To keep ourselves sharp and on the top of our game, we need to practice our procedural skills at intervals, ideally before we fall below that level of competence. When this will occur depends on the individual and the procedure. Truly rare and complex procedures like transvenous pacing (TVP) will require more frequent and more intensive practice, but the good news is that with each interval training the durability of competence will extend out further and further, and the time between training can grow longer and longer (Figure 5).

HOW TO ACTUALLY PRACTICE

How we do this is very important. It is usually not enough to passively reflect on a procedure. Cognitive science teaches us that the best way to learn and improve on a skill for long term retention is through deliberate practice.

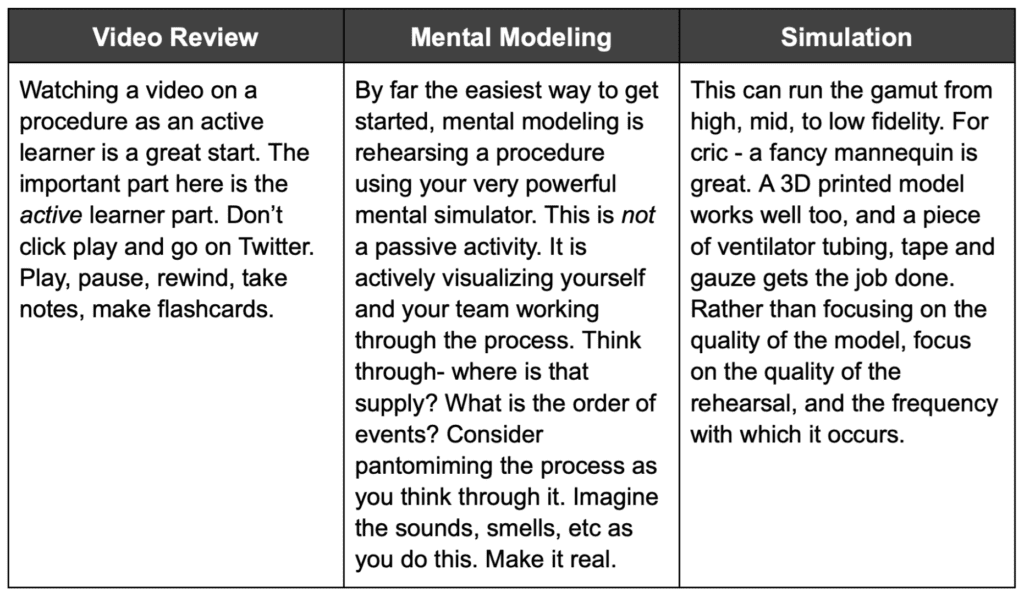

As we dive further into the The How remember the following: Anything Is Better Than Nothing. In this we mean any step you take toward more deliberate and targeted procedural training is better than your current status quo. In doing this practice, there are 3 ways it can be easily implemented:

-

- Video Review: Watching a video on a procedure as an active learner is a great start. The important part here is the active learner part. Don’t click play and go on Twitter. Play, pause, rewind, take notes, make flashcards.

- Mental Modeling: By far the easiest way to get started, mental modeling is rehearsing a procedure using your very powerful mental simulator. This is not a passive activity. It is actively visualizing yourself and your team working through the process. Think through- where is that supply? What is the order of events? Consider pantomiming the process as you think through it. Imagine the sounds, smells, etc as you do this. Make it real.

- Sim: This can run the gamut from high, mid, to low fidelity. For cric – a fancy mannequin is great. A 3D printed model works well too, and a piece of ventilator tubing, tape and gauze gets the job done. Rather than focusing on the quality of the model, focus on the quality of the rehearsal, and the frequency with which it occurs.

THE IMPORTANCE OF STRESS

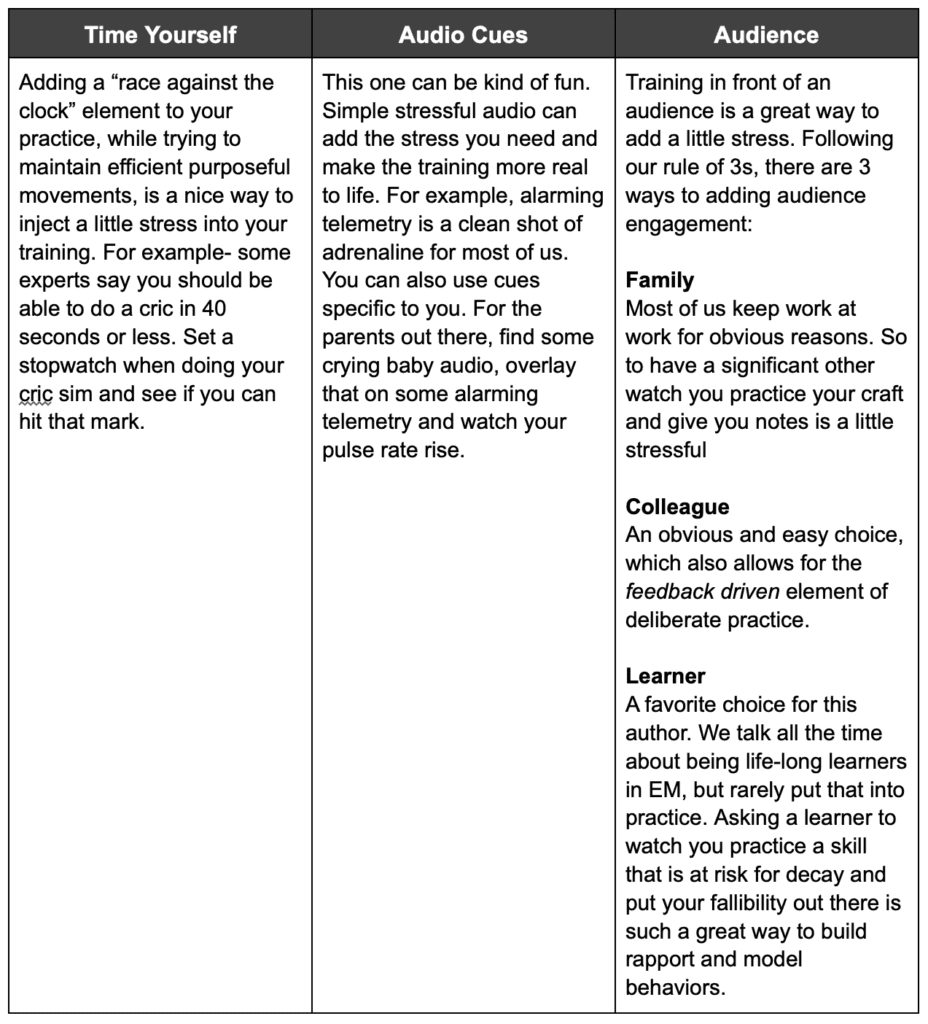

When doing this training, consider adding stress inoculation to the practice. This is the concept of purposefully making the practice stressful and it serves two purposes: 1) It more accurately reflects the environment where the procedure is to be performed and 2) it increases your retention of the learning. Cognitive science again shows us that a little bit of stress helps with encoding a memory. While lots of stress is deleterious, we will never try for or achieve that in our sim training : )

Adding small amounts of stress inoculation is pretty easy, below are 3 simple ways:

- Time yourself- Adding a “race against the clock” element to your practice, while trying to maintain efficient purposeful movements, is a nice way to inject a little stress into your training. For example- some experts say you should be able to do a cric in 40 seconds or less. Set a stopwatch when doing your cric sim and see if you can hit that mark.

- Audio cues– This one can be kind of fun. Simple stressful audio can add the stress you need and make the training more real to life. For example, alarming telemetry is a clean shot of adrenaline for most of us. You can also use cues specific to you. For the parents out there, find some crying baby audio, overlay that on some alarming telemetry and watch your pulse rate rise.

- Audience- Training in front of an audience is a great way to add a little stress. Following our rule of 3s, there are 3 ways to adding audience engagement:

-

- Family- Most of us keep work at work for obvious reasons. So to have a significant other watch you practice your craft and give you notes is a little stressful.

- Colleague- An obvious and easy choice, which also allows for the feedback driven element of deliberate practice.

- Learner- A favorite choice for this author. We talk all the time about being life-long learners in EM, but rarely put that into practice. Asking a learner to watch you practice a skill that is at risk for decay and put your fallibility out there is such a great way to build rapport and model behaviors.

SUMMARY

- We learn and forget things, including procedures, with time and this can be graphed as an Experience Curve.

- Spaced training is important to keep ourselves above that line of competence.

- This training is best and most efficiently done with short training sessions spaced out through time. short spaced segments of procedural practice.

-

This practice can be:

- Active Video Review

- Mental Modeling

- Simulation

-

Stress should be inoculated into this training and can be added through:

- Timing yourself

- Audio cues

- Performing in front of an audience

- Finally, remember Anything Is Better Than Nothing. Anything you add today after reading this post is better than your current status quo. Our simple call to action is to take out your smart phone and put in a reminder “Practice procedures” and have it repeat monthly.

Keeping yourself sharp in these critical procedures can take a bit of work and dedication. SimKit is a medical education company looking to make this process painless and fun. With procedural simulation kits delivered to you monthly, you can practice and hone your skills when and where you choose. Check out their offerings HERE.

Guest Post By:

References

- Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Acad Med. 2004. PMID: 15383395.

- Pusic MV, Kessler D, Szyld D, Kalet A, Pecaric M, Boutis K. Experience curves as an organizing framework for deliberate practice in emergency medicine learning. Acad Emerg Med. 2012. PMID: 23230958.

- Branzetti JB, Adedipe AA, Gittinger MJ, Rosenman ED, Brolliar S, Chipman AK, Grand JA, Fernandez R. Randomised controlled trial to assess the effect of a Just-in-Time training on procedural performance: a proof-of-concept study to address procedural skill decay. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. PMID: 28866621.

- Hughes PG, Crespo M, Maier T, Whitman A, Ahmed R. Ten Tips for Maximizing the Effectiveness of Emergency Medicine Procedure Laboratories. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016. PMID: 27214775.

- Arthur W, Bennett W, Stanush P, McNelly T. Factors That Influence Skill Decay and Retention: A Quantitative Review and Analysis. Human Performance. 1998. 11(1):57 – 101. (Link is HERE).

- Kovacs G, Bullock G, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Cain E, Petrie D. A randomized controlled trial on the effect of educational interventions in promoting airway management skill maintenance. Ann Emerg Med. 2000. PMID: 11020676.

- Maehle V, Cooper K, Kirkpatrick P. Absolute clinical skill decay in the medical, nursing and allied health professions: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017. PMID: 28628511.

- Kluge A, Frank B. Counteracting skill decay: four refresher interventions and their effect on skill and knowledge retention in a simulated process control task. Ergonomics. 2014. PMID: 24382262.

- Wang EE, Quinones J, Fitch MT, Dooley-Hash S, Griswold-Theodorson S, Medzon R, Korley F, Laack T, Robinett A, Clay L. Developing technical expertise in emergency medicine–the role of simulation in procedural skill acquisition. Acad Emerg Med. 2008. PMID: 18785939.

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Don’t Become Obsolete: The EM Physician’s Fight Against Procedural Decay appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.