Background: Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization among adults over the age of 65 years of age. Despite improvement in outcomes with optimal medical treatment, admission rates still remain high with many patients requiring rehospitalization. The staples of CHF management include ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, diuretics, aldosterone antagonists, hydralazine/nitrates, and digoxin. Recently, I have seen an increase of patients with CHF on a new medication called Entresto (Valsartan-Sacubitril or LCZ696) I did not know much about this medication, or the evidence base for it.

Background: Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization among adults over the age of 65 years of age. Despite improvement in outcomes with optimal medical treatment, admission rates still remain high with many patients requiring rehospitalization. The staples of CHF management include ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta blockers, diuretics, aldosterone antagonists, hydralazine/nitrates, and digoxin. Recently, I have seen an increase of patients with CHF on a new medication called Entresto (Valsartan-Sacubitril or LCZ696) I did not know much about this medication, or the evidence base for it.

Medication Basics:

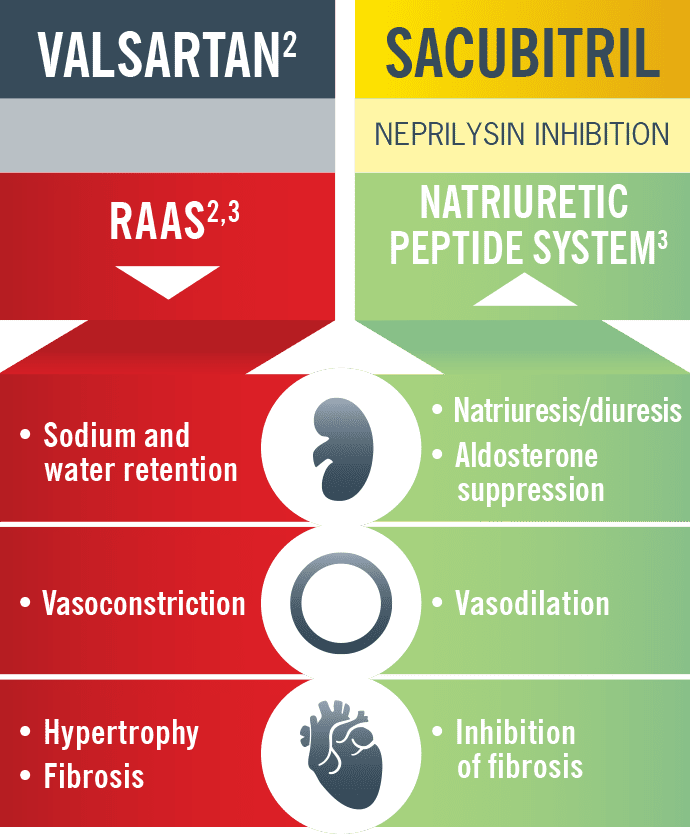

Entresto is a novel medication that acts by inhibiting neprilysin, a neutral endopeptidase that degrades endogenous vasoactive peptides (brain natriuretic peptide, adrenomedullin, and bradykinin). By inhibiting neprilysin, there is an increase in vasoactive peptides which decreases vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and cardiac remodeling. An important point to note here is that by inhibiting neprilysin, we will see an increase in natriuretic peptide (i.e. falsely elevated BNP).

Image from Entresto Website

This medication was funded by big pharma, and evaluated by the FDA by a fast track designation, which allowed a faster release than usual. So let’s look at the evidence….

Entresto Evidence:

PARADIGM-HF (Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure) [1]

What They Did: This was a double-blind randomized trial that planned to enroll 8,442 patients comparing the angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) LCZ696, also known as Entresto, with enalapril in patients with congestive heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction (Class II – IV heart failure and an EF of ≤40%). There were three phases to this trial, which included a single run-in period during which all patients were transitioned to enalapril at a dose of 10mg PO BID for 2 weeks. If there were no untoward side effects, another single run-in period during which patients received LCZ696 for an additional 4 – 6 weeks at a dose of 100mg PO BID and ultimately increased to 200mg PO BID, again to ensure acceptable side-effect profiles of the study drug. Finally, after this 6 – 8 week run in period, patients could be randomized in a double-blind treatment strategy.

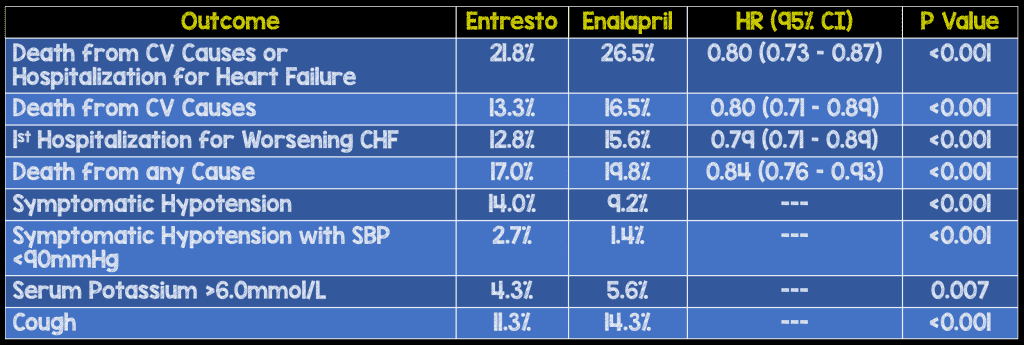

Outcomes: The primary outcome was a composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes or hospitalization for heart failure, but it is important to note that the trial was powered to detect differences in the rates of death from cardiovascular causes. Secondary outcomes were time to death from any cause, symptom score, time to new onset atrial fibrillation, and time to first occurrence of worsening renal function.

Inclusion:

- ≥18 years of age

- New York Heart Association (NHYA) class II – IV

- Ejection fraction ≤40% (Later changed to ≤35%)

Exclusion:

- Symptomatic hypotension (SBP <100mmHg at screening or <95mmHg at randomization)

- eGFR <30mL/min/1.73m2

- Serum potassium level of >5.2mmol/L at screening (or above 5.4 mmol/L at randomization)

- History of angioedema

Results (Trial stopped early after only 25% enrollment):

- No difference in new onset atrial fibrillation or decline in renal function between groups

- Angioedema was very rare and never caused airway compromise

Discussion:

- This trial was stopped early after only 25% enrollment of their intended population due to an interim efficacy analysis. This has to make you wonder would there have been a regression to the mean if the study continued? A great example of this can be seen with the ADRENAL trial, where two prespecified interim analyses were performed at 25% and 66% enrollment. In the first interim analysis hydrocortisone had lower mortality compared to placebo (28.3% vs 33.5%), by the 66% enrollment mark there was not as much a mortality benefit (27.1% vs 29.5%), and we all know that the final numbers showed no statistical difference in mortality. This is why larger trials are better than smaller trials, as the risk of chance alone goes down, as you get a regression to the mean. Guess we won’t know as the authors felt the trial should be stopped after the third interim efficacy analyses, stating that the prespecified stopping boundary for an overwhelming benefit had been crossed.

- Composite outcomes are used to help boost the power of studies results while reducing the number of patients you would need to get to a statistically significant endpoint. This is great as a researcher, but for interpretation it makes it difficult to conclude which outcome is affected by an intervention. It is not as big a deal when the endpoints are relatively similar in clinical importance, but it is more difficult when they are not. Is it fair to compare being re-admitted to the hospital vs dying from cardiovascular causes? In these cases it is important to know which component of the composite outcome is the primary driver of statistical significance.

- The dosage of combination sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) was maximized to 200mg-320mg in the intervention group while in the control group a fixed dose of enalapril 10mg PO BID was used. This highlights two very important points. The first is, why was the study, not a comparison of sacubitril-valsartan to valsartan alone? The second issue is that the enalapril dose was relatively lower than the valsartan dose (Enalapril on the lower end of it’s dosage range and valsartan on the high range of it’s dosage range), causing baseline differences between groups favoring the intervention group. These two points both cause cofounding bias. It is unclear if the benefits seen in this study are due to neprilysn inihibition or greater blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system due to the apples to oranges comparisons.

- Something that might be glanced over upon first reading is the interesting three part “run-in” methodology of this trial. The reason this is interesting is that patients who had adverse reactions initially were withdrawn from the analysis. Therefore this study is only pertinent to patients who were tolerant of the medication and not a safety study. During “run-in” period one, 5.6% or 591 patients withdrew from the study due to adverse events. During “run-in” period 2, 5.8% or 547 patients withdrew due to adverse events. This means ≈12% of patients were not included in the final analysis for safety monitoring, falsely lowering the adverse event rate in this trial.

- Any study that is funded by a pharmaceutical company that is intricately involved in the methodology, statistical analysis, and results should make you skeptical. It does not mean that all studies funded and run by pharmaceutical companies are bad, but it does mean that the likelihood of “hocus pocus” statistics is high. This study was funded by Novartis the company that makes Entresto (valsartan-sacubitril).

Author Conclusion: “LCZ696 was superior to enalapril in reducing the risks of death and of hospitalization for heart failure.”

Clinical Take Home Point: Entresto (valsartan-sacubitril) may (or may not) be superior to standard CHF therapy in reducing death from cardiovascular causes and re-hospitalization for acute heart failure exacerbations. The PARADIGM-HF study has multiple confounding biases that make it hard to truly say, but I assure you, that you will start to see this medication being prescribed by our cardiology colleagues and it is important to know how the medication works and that it can falsely elevate BNP levels.

References:

- McMurray JJ et al. Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition Versus Enalapril in Heart Failure. NEJM 2014. PMID: 25176015

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post Industry Sponsored Trials and Entresto in CHF appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.