Background: In REBEL Cast Episode 73, Anand Swaminathan and I discussed two recent studies on the safety of peripheral vasopressors from two large trials [1][2]. An email from good friend Rory Spiegel brought my attention to yet another trial on this topic [3]. I think we can all agree that in patients with septic shock, or shock in general, the administration of vasopressor agents early, can help to stabilize patients and reverse end-organ hypoperfusion. Traditionally, this has been done through central venous catheters (CVCs) due to the hypothetical risk of extravasation injury to extremities. The flip side of this is, that central venous catheters are not without their own risks and time to place them can delay a therapy that may benefit patients.

Background: In REBEL Cast Episode 73, Anand Swaminathan and I discussed two recent studies on the safety of peripheral vasopressors from two large trials [1][2]. An email from good friend Rory Spiegel brought my attention to yet another trial on this topic [3]. I think we can all agree that in patients with septic shock, or shock in general, the administration of vasopressor agents early, can help to stabilize patients and reverse end-organ hypoperfusion. Traditionally, this has been done through central venous catheters (CVCs) due to the hypothetical risk of extravasation injury to extremities. The flip side of this is, that central venous catheters are not without their own risks and time to place them can delay a therapy that may benefit patients.

Previous Evidence

A systematic review by Loubani et al in 2015 [4] looked at 85 articles with 270 patients (all case reports and case series), mostly published prior to 1969 summarized risk factors for extravasation including: longer duration of peripheral infusion (96.8% of adverse events occurred with infusions running ≥4hrs) and more distal locations (85.3% of extravasation events occurred in peripheral intravenous access distal to antecubital and popliteal fossae).

Looking through the literature, the rate of extravasation through peripheral intravenous access ranges from 3 – 6% [1][5]. There was one study by Pancaro et al [2] that was a perioperative database from the Netherlands. This study quoted a 0.035% rate of extravasation; however, these were non-critically ill patients, getting small doses of vasopressors (dose range 0.02 – 0.05ug/kg/min) short infusion times (≈20min), and small volumes that extravasated (1.5 – 4mLs). More importantly, none of these studies reported any episodes of tissue necrosis or limb ischemia (an important patient-oriented outcome).

What They Did:

- Single-center, retrospective chart review conducted at a New York tertiary care academic teaching hospital

- During this time period, the institution did not have a protocol in place for best practices of the administration of vasopressor agents through a PIV

- Dose of vasopressor at time of extravasation was converted to norepinephrine equivalents

- Norepinephrine Equivalents = (norepinephrine [ug/min]) + dopamine [ug/kg/min]/2) + (epinephrine [ug/min]) + (phenylephrine [ug/min/10]) + (vasopressin [units/h] x 8.33)

Important Criteria:

Outcomes:

-

Primary: Incidence of extravasation events related to peripheral administration of a vasopressor

- Extravasation = “The extravenous administration of a medication or solution that has the potential for severe tissue or cellular damage in the surrounding tissue.”

-

Secondary:

- Description of dose, concentration, and duration of peripheral vasopressor use

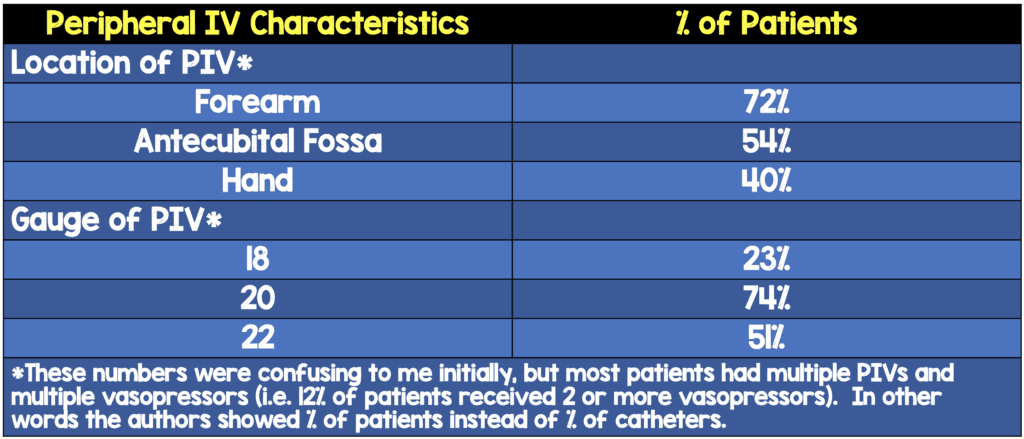

- Location and gauge of PIV used for vasopressor administration

- Frequency and time until CVC insertion

Inclusion:

- ≥18 years of age

- Receiving a vasopressor agent through a PIV

- Admitted to the ICU

Exclusion:

- Already had CVC in place

- Received vasopressors via a PIV for <1hr

Results:

- 485 patients received a vasopressor

- 283 patients were excluded as they had CVC at time of initiation of vasopressors

- 202 patients were evaluated for the incidence of extravasation events related to vasopressors through a PIV

- 340 peripheral catheters available for assessment (Most patients had multiple PIVs)

- Total Median Duration of Peripheral Vasopressor Administration = 11.5hrs

- Patients not Transitioned to CVC, Median Duration of Peripheral Vasopressor Administration = 19hrs

- Most common indications for vasopressors: septic shock (73%) and Cardiogenic shock (14%)

- Most common location of patients: Medical ICU (45%) and Medical stepdown unit (42%)

*These numbers were confusing to me initially, but most patients had multiple PIVs and multiple vasopressors (i.e. 12% of patients received 2 or more vasopressors)

- Transition to CVC: 46%

- Median Time to CVC Insertion: 6hr (Range 3 – 23hrs)

-

Extravasation Events (Primary Outcome):

- 8/202 patients (4%)

- Median time until extravasation = 21hrs

- Median dose of vasopressor in norepinephrine equivalents at time of extravasation = 0.11ug/kg/min (8ug/min)

- All lines except for 1 (external jugular) were inserted at or distal to the antecubital fossa

-

No ischemia or necrosis in any of the extravasation events

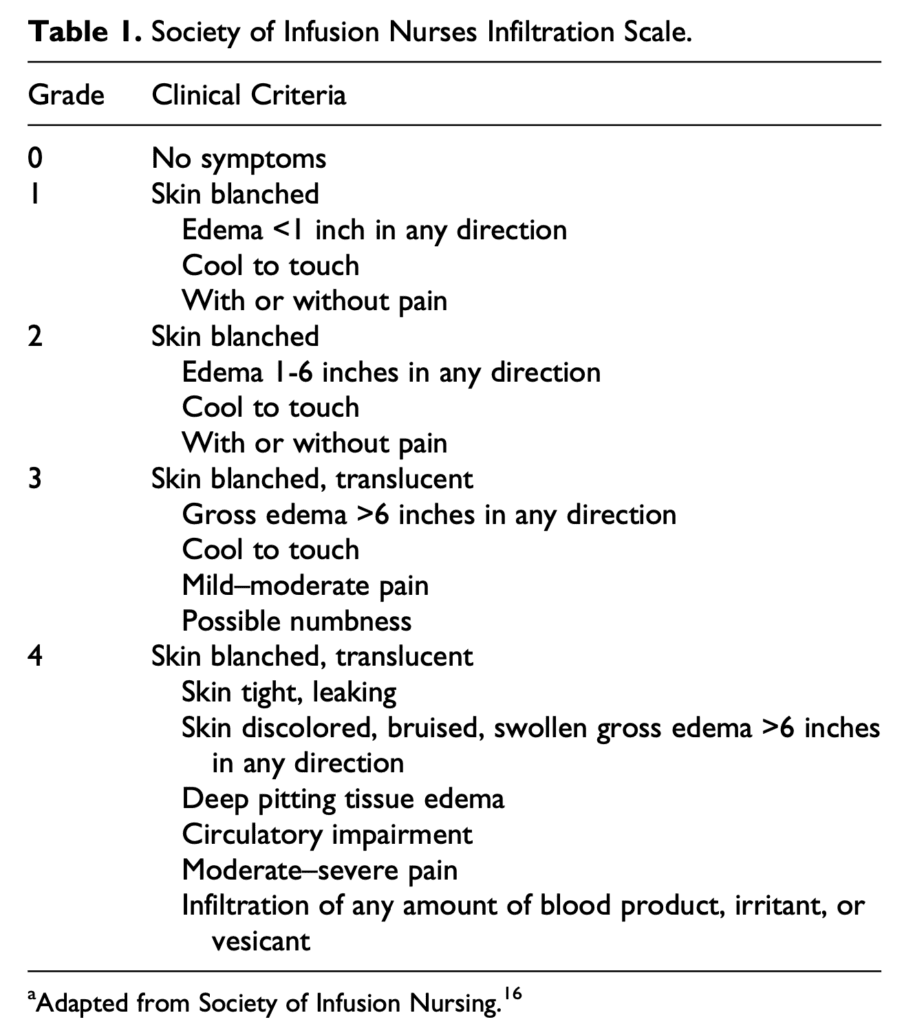

- 6/8 events (75%) resulted in grade 1 injury (skin blanching & edema <1in)

- 2/8 events (25%) resulted in grade 2 injury (skin blanching & edema 1 – 6in)

- 7/8 (88%) events resulted in restarting vasopressor peripherally

Strengths:

- Collected vasopressor infusion data including concentration, duration, dose, and time to CVC where applicable

- Collected data on extravasation events including time to extravasation, location and gauge of the PIV, any corrective measure, and grade of severity of the event

- Objectively defined extravasation and used an infiltration scale to grade extravasation events

- ≈50% of patients had 2 or more comorbid conditions that increased the risk of extravasation, variable vasopressor concentrations/dosing used, PIVs placed in high-risk locations, monitoring of PIVs occurring every 4 hours, and no protocol for management of extravasation events. Although this is not best practice, it is most likely the reality in which many use vasopressors through PIVs

Limitations:

- Small, single center study. Without knowledge of baseline incidence of severe extravasation events from PIVs, the sample size may not be large enough to capture severe extravasation events

- Retrospective chart review making the information only as good as what is documented in the EMR (reporting and documentation bias). In other words, there may have been events that were not captured or documented in the EMR.

- The 8 extravasation events documented in this study had highly variable PIV size/location, vasopressor used and dose. Because of this and due to the low number of events it is difficult to make any recommendations based on this study alone

- Although there were no patients with ischemia or necrosis requiring surgical management, only 3 out of 8 patients had details of the local tissue injury reported

- Despite a low complication rate (≈4%) in this study, without a control group, no definitive statements can be made about delivering vasopressors through a PIV vs CVC

Discussion:

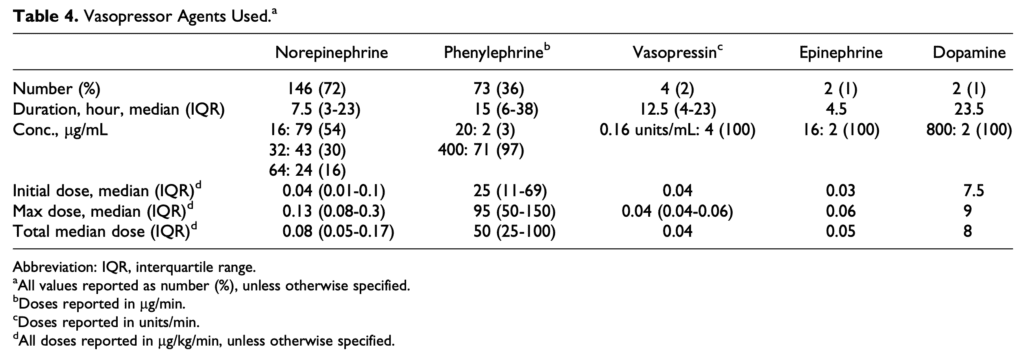

- Most common vasopressor administered = Norepinephrine (72%) with median duration of 7.5hrs

- Most common concentration of norepinephrine used = 16ug/mL

- Median dose of norepinephrine = 0.08ug/kg/min (Range: 0.04ug/kg/min to 0.13ug/kg/min)

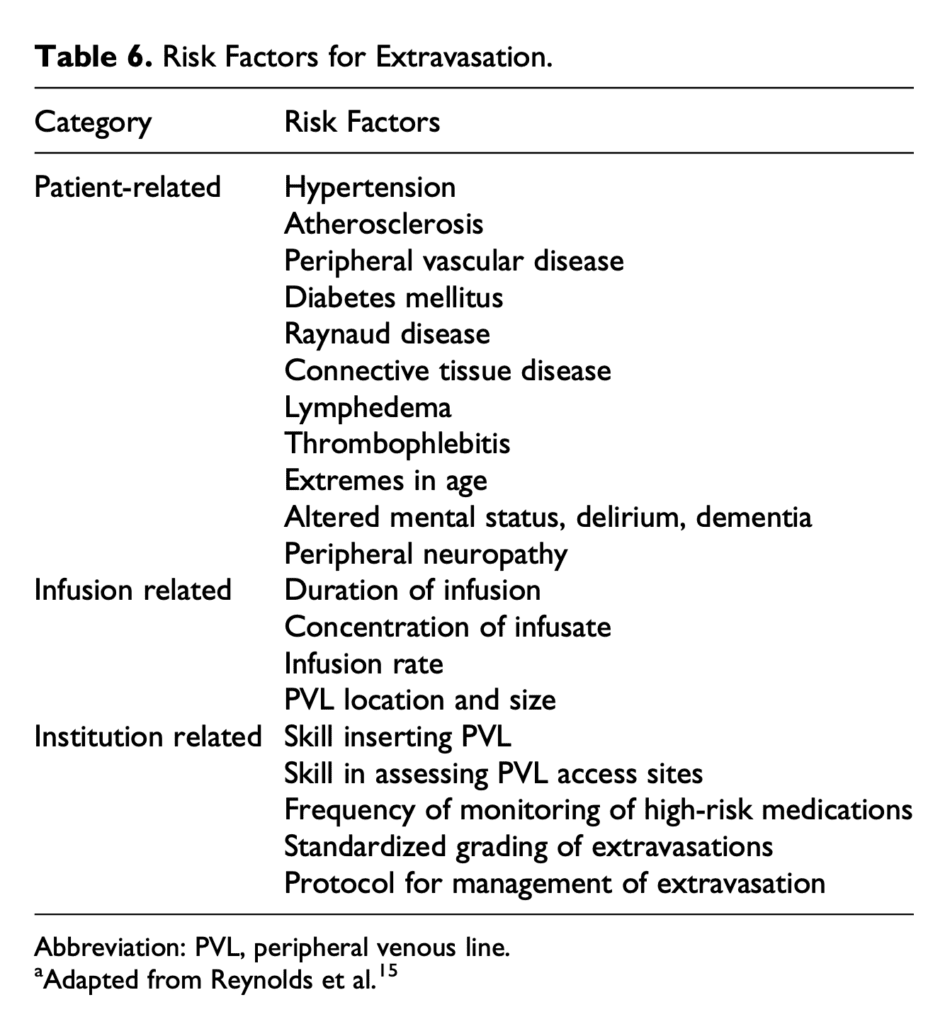

- Risk factors for Extravasation:

- Patient-specific = Factors that impair blood flow or weaken blood vessels and inability to sense or report pain

- Vasopressor-Specific = Concentration of drug, infusion rate, and duration of infusion

- Institution-Specific = Skill in getting access, frequency of monitoring, and protocol for management

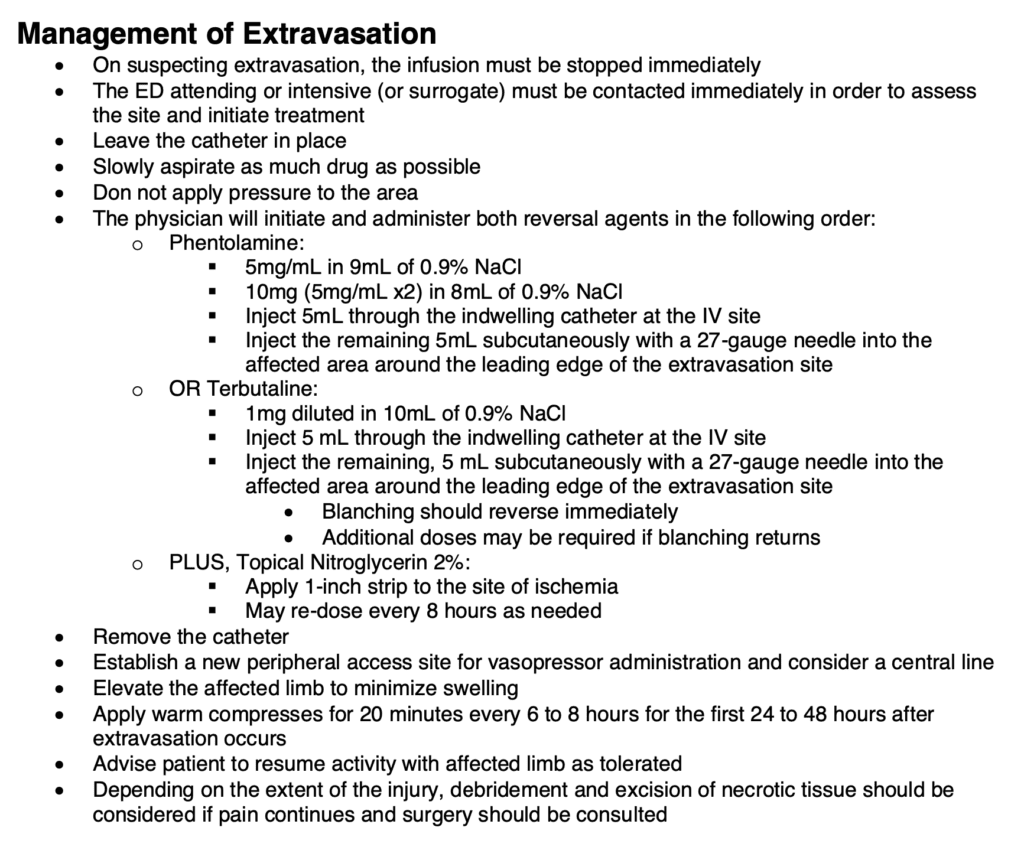

- My favorite thing about this publication is they publish their protocols (Permission given by lead author for publication) for using vasopressors through PIVs: Peripheral Vasopressor Protocol

- Here is a sample of the Peripheral Vasopressor Protocol:

Author Conclusion: “We found an overall incidence of extravasation events of 4% in patients receiving vasopressors through a PVL that were not managed under a strict safety protocol. None of these events were severe enough to require the use of an antidote or surgical intervention, and in 7 of the 8 cases vasopressors were resumed at a separate peripheral site.”

Clinical Take Home Point: This study, although retrospective and single center (serious methodological limitations) adds to the knowledge of using vasopressors through peripheral IVs. The documented risk for extravasation injury of 4% in this study is similar to extravasation rates seen in prior publications (i.e. 3 – 6%) and there were zero cases of limb ischemia or necrosis requiring surgical intervention. Hypothetically, the extravasation rate can be further reduced by implementation of a strict observation protocols and extravasation management protocols.

References:

- Tian DH et al. Safety of Peripheral Administration of Vasopressor Medications: A Systematic Review. EMA 2019. PMID: 31698544

- Pancaro C et al. Risk of Major Complications After Perioperative Norepinephrine Infusion Through Peripheral Intravenous Lines in a Multicenter Study. Anesth Analg 2019. PMID: 31569163

- Lewis T et al. Safety of the Peripheral Administration of Vasopressor Agents. J Intensive Care Med 2019. PMID: 28073314

- Loubani OM et al. A systematic review of extravasation and local tissue injury from administration of vasopressors through peripheral intravenous catheters and central venous catheters. J Crit Care 2015.PMID: 25669592

- Medlej K et al. Complications form Administration of Vasopressors Through Peripheral Venous Catheters: An Observational Study. JEM 2018. PMID: 29110979

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- REBEL EM: Mythbuster – Administration of Vasopressors Through Peripheral Intravenous Access

- REBEL EM: Peripheral Vasopressors – Safe or Dangerous?

- REBEL EM: REBEL Cast Ep73 – Are Peripheral Vasopressors Safe?

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post One More Update on Using Peripheral Intravenous (PIV) Vasopressors appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.