The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has strained our available healthcare resources and caused unprecedented stress in the lives of our healthcare workers. With the advent of COVID-19 and the resultant deaths of our colleagues, it has become painfully clear that our profession has become inherently dangerous. It is ethically sound to expect the provision of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) before treating patients with infectious diseases.1 To borrow from our pre-hospital counterparts, when responding in dangerous situations the utmost priority is your personal safety and the safety of your teammates, and only once these have been assured are we able to attend to the needs of the victim/patient. However, we cannot be frozen by fear and through the proper and appropriate use of PPE, clinicians can safely uphold the sacred duty to care for the ill. Following the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, a study analyzed the nosocomial infections in Hong Kong healthcare workers. Standardized PPE contact and droplet precautions included a mask, gloves, gowns, and handwashing. Notably, none of the personnel who utilized all four measures were infected with SARS. Contrastingly, all of the healthcare workers with nosocomial infection had failed to implement at least one of the PPE methods.2 We have confidently and effectively employed PPE against airborne, droplet, and contact pathogens for years (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, H1N1 influenza A, Clostridium difficile). Now, as we battle COVID-19, similar to lessons learned on the battlefield and taught in Tactical Combat Casualty Care, we must first engage in suppression of the threat prior to initiating patient care.3

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has strained our available healthcare resources and caused unprecedented stress in the lives of our healthcare workers. With the advent of COVID-19 and the resultant deaths of our colleagues, it has become painfully clear that our profession has become inherently dangerous. It is ethically sound to expect the provision of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) before treating patients with infectious diseases.1 To borrow from our pre-hospital counterparts, when responding in dangerous situations the utmost priority is your personal safety and the safety of your teammates, and only once these have been assured are we able to attend to the needs of the victim/patient. However, we cannot be frozen by fear and through the proper and appropriate use of PPE, clinicians can safely uphold the sacred duty to care for the ill. Following the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak, a study analyzed the nosocomial infections in Hong Kong healthcare workers. Standardized PPE contact and droplet precautions included a mask, gloves, gowns, and handwashing. Notably, none of the personnel who utilized all four measures were infected with SARS. Contrastingly, all of the healthcare workers with nosocomial infection had failed to implement at least one of the PPE methods.2 We have confidently and effectively employed PPE against airborne, droplet, and contact pathogens for years (e.g. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, H1N1 influenza A, Clostridium difficile). Now, as we battle COVID-19, similar to lessons learned on the battlefield and taught in Tactical Combat Casualty Care, we must first engage in suppression of the threat prior to initiating patient care.3

Partially due to a suspected increased SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization risk posed by high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC)and non-invasive ventilation (NIV) methods, experts initially recommended the performance of early endotracheal intubation if more than 6 liters per minute via nasal cannula was required to maintain oxygen saturations above 92%. This has led to the commonplace implementation of institutional policies against HFNC or NIV use for individuals with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is not clear that the use of these devices increases viral aerosolization or the risk of nosocomial infections in health-care workers.4 Increasingly, questions have been raised whether we are intubating these patients too early and whether they may be better served with alternative methods of oxygenation and ventilation.5 Furthermore, this approach is also supported by national and international organizations. With the selection of appropriate patients, both HFNC and NIV are included in the COVID-19 treatment recommendations released by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (a joint initiative of the ESICM and SCCM) and the World Health Organization.6,7 As previously discussed on REBELEM,8 studies suggest that aerosolization may be greatly reduced during the use of HFNC with the addition of the patient wearing a surgical mask.9,10 The Italians have described methods they have employed to mitigate aerosolization during NIV,11 and the American College of Chest Physicians recommends that chronically ill home-based ventilation patients have their personal equipment converted to include viral filtration if hospitalized.12 Additionally, the use of HFNC and NIV also allows for awake proning,8 which releases a ventilator to be used in more severe cases and reduces the use of increasingly scarce intravenous sedation medications.

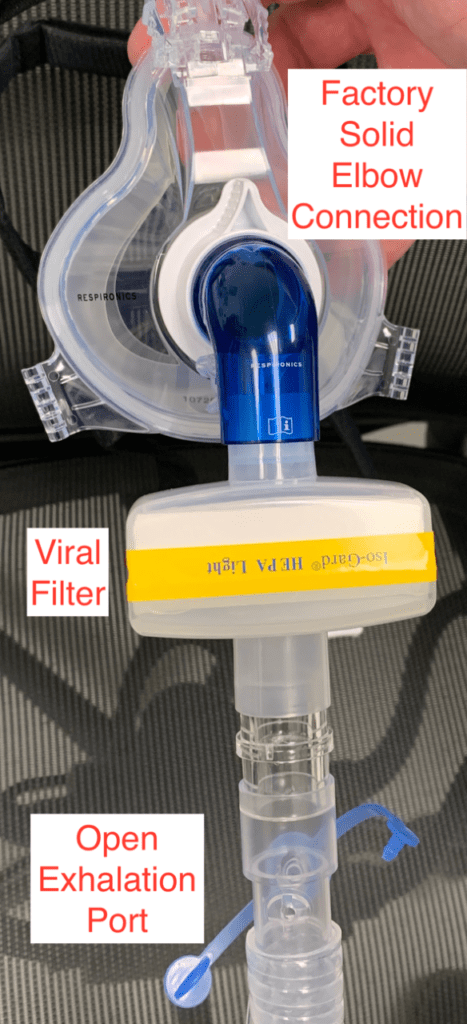

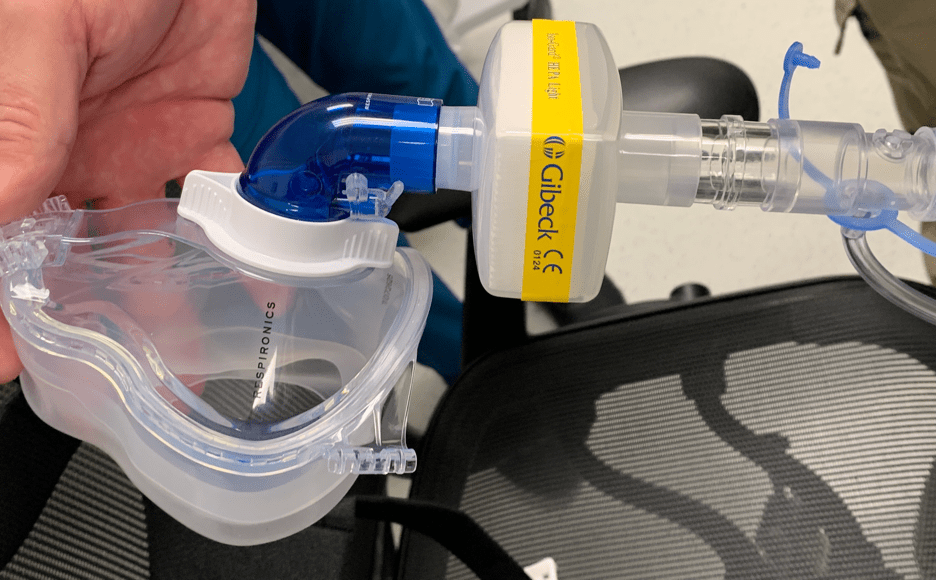

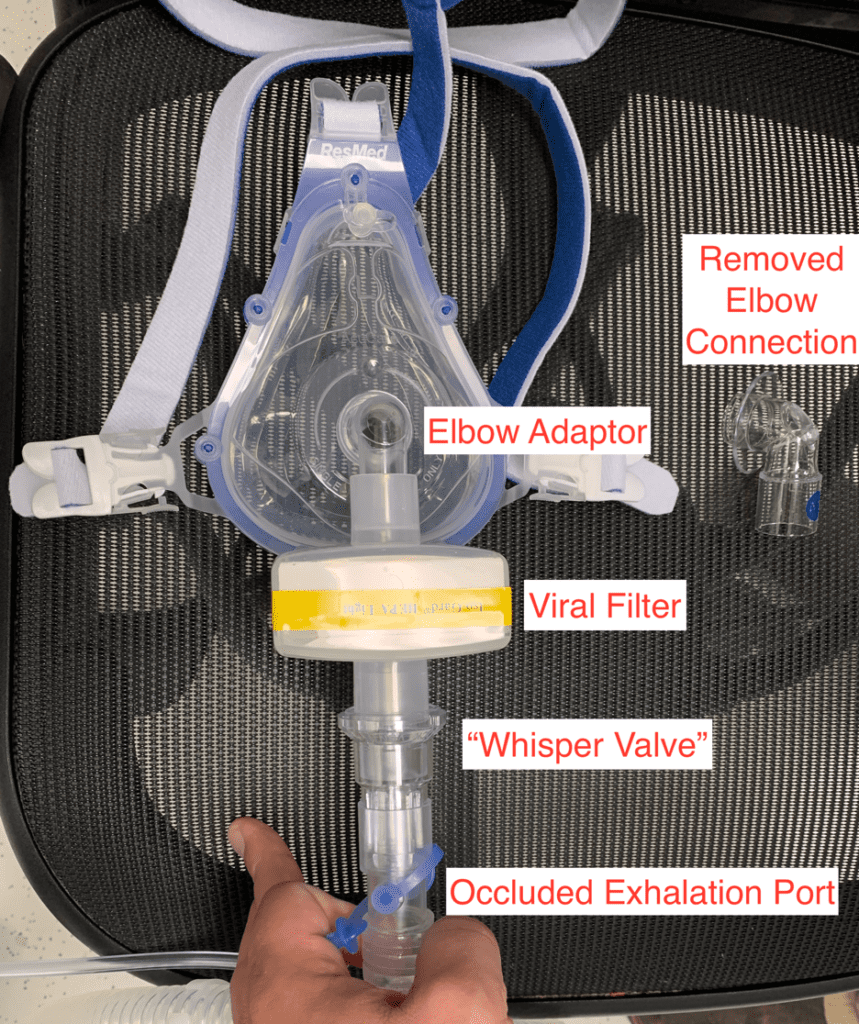

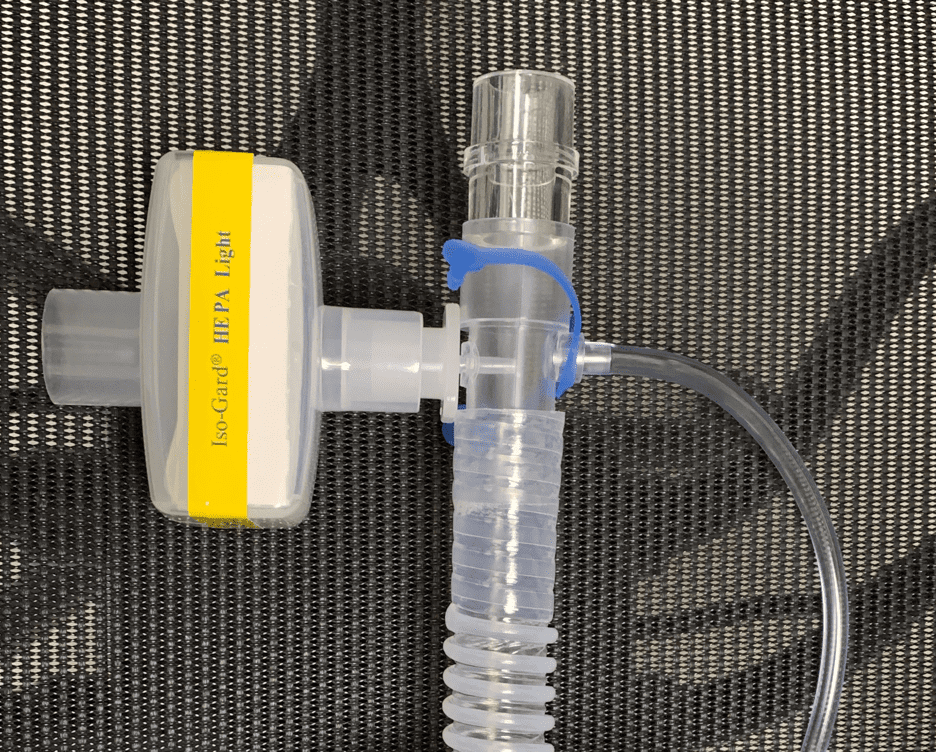

Implementation at your clinical site will require experimentation with the supplies available in your facility, in addition to buy-in from your clinical leadership and your nursing and respiratory therapy collaborators. If available, non-vented masks should be used preferentially. Although, if these are not available, vented masks can be converted as shown below. The key feature is that any configuration must include an interface to allow for the placement of a viral filter in-line before the exhalation port. If supplies such as a “Whisper” valve are not available, a pediatric endotracheal tube connection can adapt the exhalation port to fit a viral filter. NIV requires the selection of an appropriate patient that is mentating well and frequent reassessment for deterioration is necessary. However, if the patient deteriorates and requires intubation, each of the configurations can attach to an endotracheal tube and allows the BiPAP machine to function as a ventilator with the PCV or AVAPS mode without the need to immediately assign purpose-built equipment.

CPAP Mask with Solid Elbow Connector (Blue)

ResMed Mask (Factory mask elbow must be removed – takes a little force to pop out) Replaced with Solid Elbow Used on our Current Vents and Whisper Valve

Pediatric 2.5 Endotracheal Tube fits the BiPAP Exhalation Port and Viral Filter

COVID-19 has rapidly become a worldwide scourge, but this pandemic is differentiated from all that precedes it by the rapid sharing of information and lessons-learned through social media and FOAMed. Stay safe, continue to share, adapt, improvise, and together we will ultimately overcome.

Guest Post By:

Ryan P. Bierle DMSc, PA, LP

University of Texas Health – San Antonio, School of Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care Medicine

San Antonio, TX

References:

- Maguire B et al. The Ethics of PPE and EMS in the COVID-19 Era. Journal of Emergency Medical Services 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Seto WH et al. Effectiveness of Precautions Against Droplets and Contact in Prevention of Nosocomial Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Lancet 2003. PMID: 12737864

- Callaway DW. Translating Tactical Combat Casualty Care Lessons Learned to the High-Threat Civilian Setting: Tactical Emergency Casualty Care and the Hartford Consensus. Wilderness Environ Med 2017. PMID: 28392170

- Phua J et al. Intensive Care Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Challenges and Recommendations. Lancet Respir Med 2020. [Epub Ahead of Print]

- Weingart S. EMCrit Wee – Stop Kneejerk Intubation with the EMCrit Crew. EMCrit. [Link is HERE]

- Alhazzani W et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med 2020. PMID: 322222812

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection (SARI) when COVID-19 Disease is Suspected. 2020. [Link is HERE]

- Rezaie S. COVID-19 Hypoxemia: A Better and Still Safe Way. REBELEM. https://rebelem.com/covid-19-hypoxemia-a-better-and-still-safe-way/. Published 2020. [Link is HERE]

- Leonard S et al. Preliminary Findings of Control of Dispersion of Aerosols and Droplets during High Velocity Nasal Insufflation Therapy Using a Simple Surgical Mask: Implications for High Flow Nasal Cannula. Chest April 2020. PMID: 32247712

- Leonard S et al. High Velocity Nasal Insufflation (HVNI) Therapy Application in Management of COVID-19. Vapotherm 2020 [Link is HERE]

- Lazzeri M et al. Respiratory Physiotherapy in Patients with COVID-19 Infection in Acute Setting: A Position Paper of the Italian Association of Respiratory Physiotherapists (ARIR). Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2020. PMID: 32236089

- Cao M et al. COVID-19 Resources: Care Recommendations for Home-Based Ventilation Patients. CHEST Foundation, American College of Chest Physicians 2020 [Link is HERE]

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post COVID-19: Macgyvering Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV) appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.