Background Information:

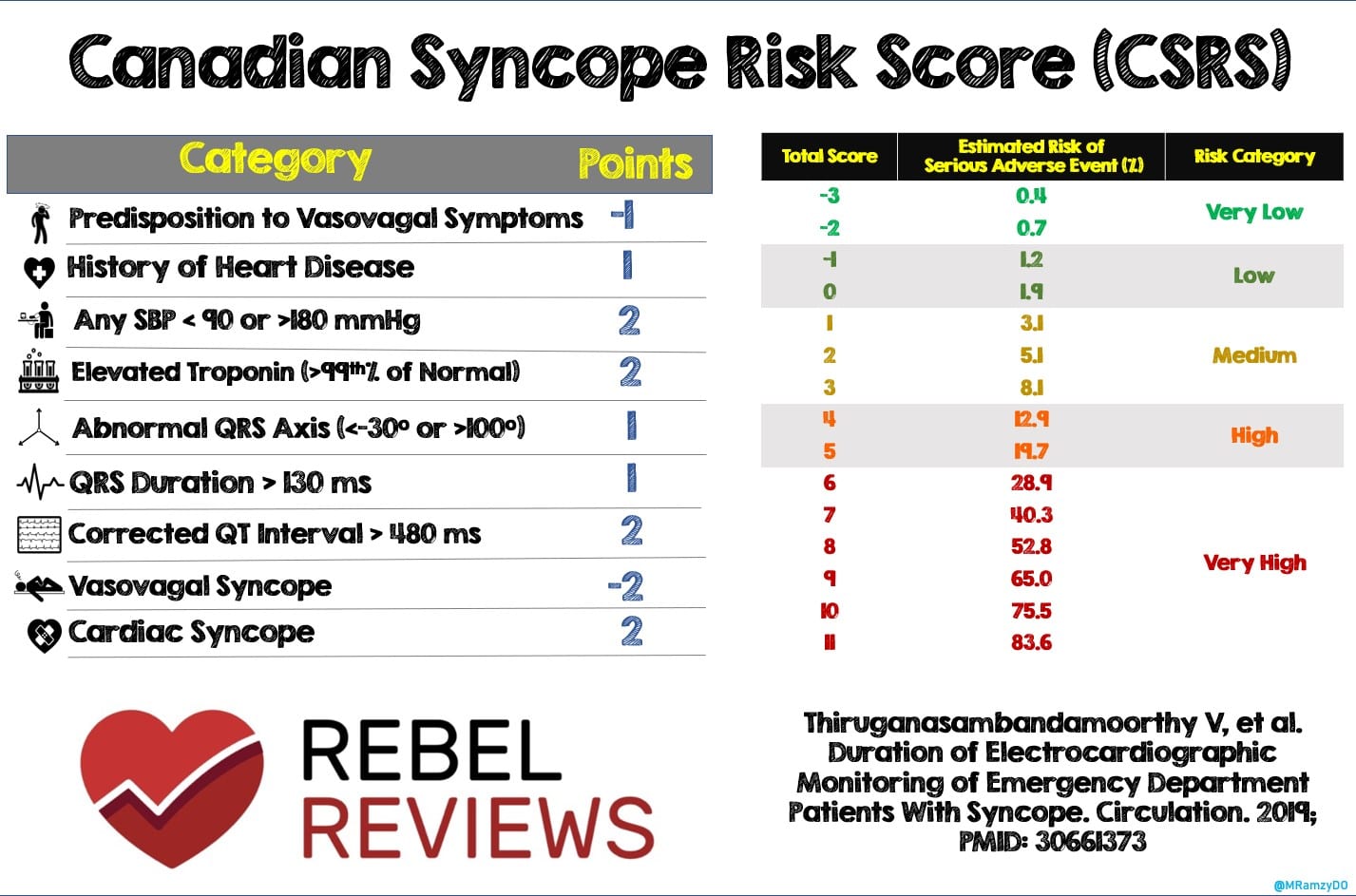

The Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS) is one of several clinical decision tools used in the emergency department (ED) following a syncopal episode. (Figure 1) It was derived from one of the largest datasets currently available and its ability to predict the probability of adverse events from a score increases its clinical utility with flexibility when applied as a continuous risk assessment.1 One benefit it has over other risk-stratification tools is the score’s ability to address the risk of these serious adverse events over 30 days as opposed to 7-30 days after the syncopal episode. The CSRS is not without its disadvantages, of which one item on the score is the clinical diagnosis. The initial clinical picture may not be clear enough to immediately discern this. Furthermore, there’s difficulty in discerning where arrhythmia falls in the score (ie. adverse event or part of the final diagnosis). While CSRS has been previously validated in a multicenter Canadian study,2 the authors of the following paper wanted to externally validate it and compare it to clinical judgement.

The Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS) is one of several clinical decision tools used in the emergency department (ED) following a syncopal episode. (Figure 1) It was derived from one of the largest datasets currently available and its ability to predict the probability of adverse events from a score increases its clinical utility with flexibility when applied as a continuous risk assessment.1 One benefit it has over other risk-stratification tools is the score’s ability to address the risk of these serious adverse events over 30 days as opposed to 7-30 days after the syncopal episode. The CSRS is not without its disadvantages, of which one item on the score is the clinical diagnosis. The initial clinical picture may not be clear enough to immediately discern this. Furthermore, there’s difficulty in discerning where arrhythmia falls in the score (ie. adverse event or part of the final diagnosis). While CSRS has been previously validated in a multicenter Canadian study,2 the authors of the following paper wanted to externally validate it and compare it to clinical judgement.

Paper: Solbiati M, et al. Multicentre external validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict adverse events and comparison with clinical judgement. Emerg Med J. May 2021 PMID: 34039646 Figure 1: Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS)

Figure 1: Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS)

Clinical Question:

- How accurate is the Canadian Syncope Risk Score in predicting serious outcomes in patients with syncope when compared with clinical judgement?

What They Did:

- Multicenter validation study that was retrospectively designed with all data prospectively collected as part of the Syncope Monitoring and Natriuretic peptides in the ED (SyMoNE) study.

- The SyMoNE study was a prospective multicenter investigation conducted at four teaching hospitals and 2 community hospitals in northern Italy assessing the role of brain natriuretic peptide and ECG monitoring in the ED management of patients with syncope

- Included in the SyMoNE study database was the ED physician’s judgement on the patients’ risk of short-term adverse events classified as low, intermediate, and high according to their clinical gestalt.

- If the ED physician categorized the patient as low risk of adverse event (ie. final diagnosis of vasovagal syncope and plan to discharge) then the patient was assigned -2 points. If the patient was categorized as high risk (ie. final diagnosis of cardiac syncope and planned disposition is hospital admission), then they were assigned 2 points. Patients deemed an intermediate risk were assigned 0 points

- The authors then compared this “clinical judgement” approach to the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (Figure 1)

- Following disposition, the authors then conducted a phone interview at 30 days to assess for the occurrence of any adverse events

Inclusion Criteria:

- Patients 18 years and older who presented to the ED for syncope

Exclusion Criteria:

- Loss of consciousness (LOC) following head trauma

- Non-spontaneous recovery of consciousness

- Episodes of falling, dizziness, or light-headedness without LOC

- LOC associated with alcohol or drug abuse

- Pregnant or breast-feeding

- Inability to provide informed consent to study participation or to complete follow-up

- Syncope as an underlying symptom of an acute condition diagnosed in the ED or requiring therapeutic intervention irrespective of syncope (ie. MI, PE, ICH, Aortic dissection, carotid sinus syndrome or arrhythmia diagnosed before ECG monitoring)

- Non-syncopal LOC (ie. History of epilepsy)

- Poor prognosis in the next 30 days for a pre-existing condition besides syncope (ie. Malignancy)

Outcomes:

Primary

- Occurrence of any of the following adverse events at 30 days:

- All-cause and syncope-related death

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Sustained and symptomatic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

- Sinus arrest with cardiac pause > 3 seconds

- Sick sinus syndrome with alternating bradycardia and tachycardia

- Second-degree type 2- or third-degree atrioventricular block

- Permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) malfunction with cardiac pauses

- Aortic stenosis <1 cm2

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with outflow tract obstruction

- Myocardial infarction

- Pulmonary embolism

- Aortic dissection

- Occult hemorrhage or anemia requiring blood transfusion

- Syncope or fall resulting in major traumatic injury (requiring admission or surgical intervention)

- Permanent pacemaker or ICD implantation

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

- Syncope recurrence requiring hospital admission

- Cerebrovascular event

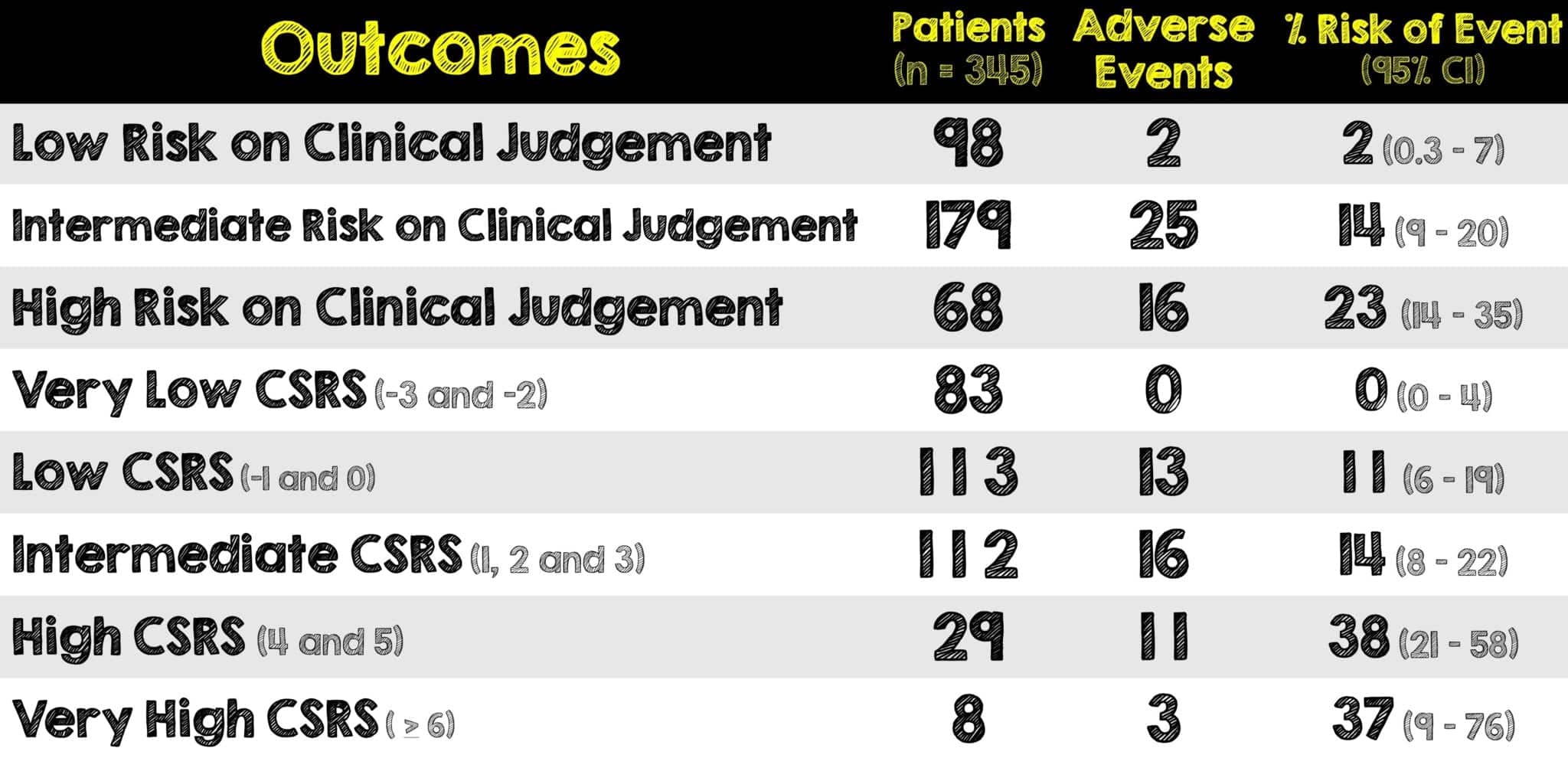

Results:

- Of the total 345 patients enrolled, 102 were hospitalized

- Troponin was measured in 178 patients and positive in 39

- 43 patients were lost to follow-up

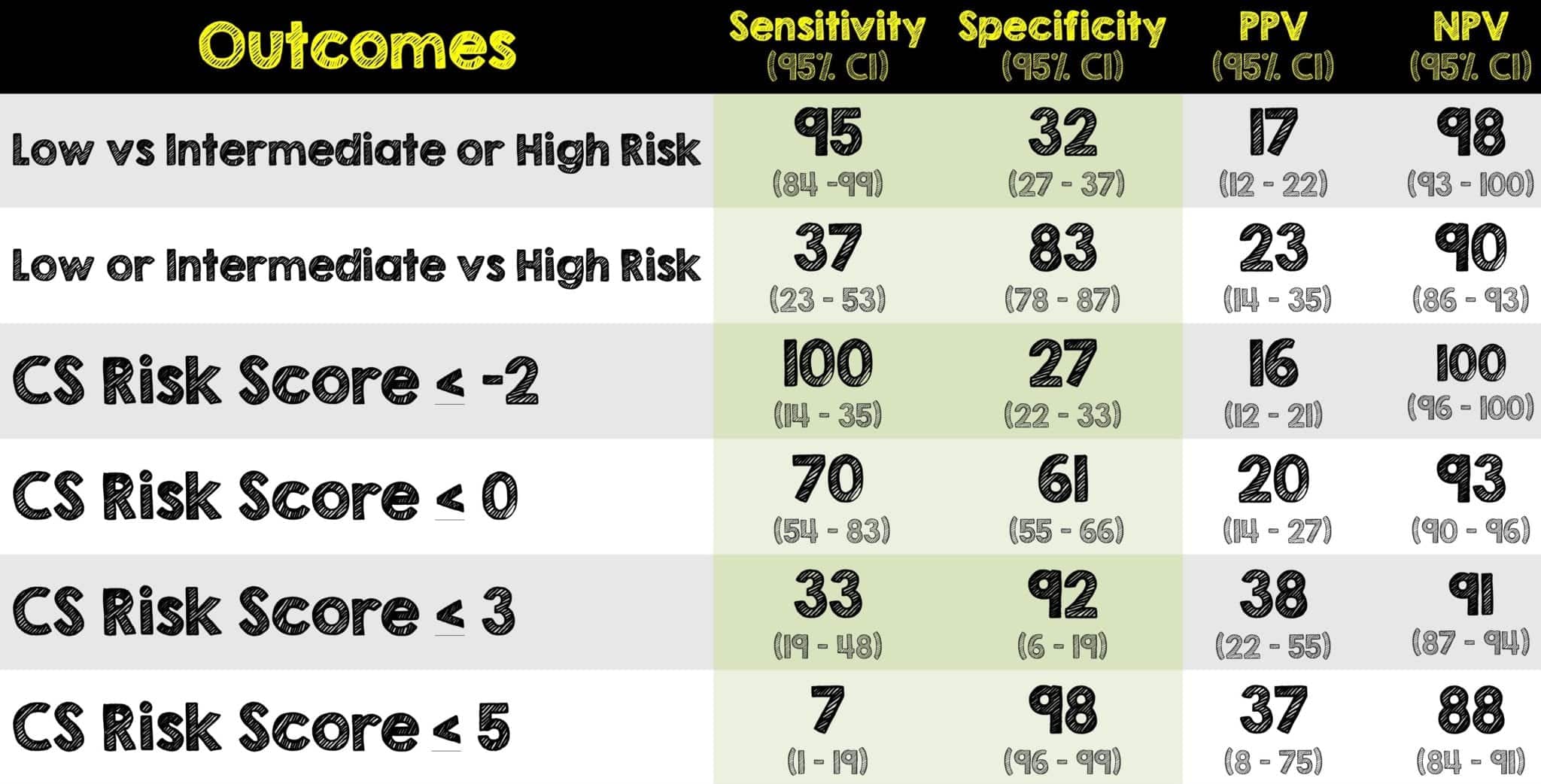

Critical Results:

- At 30-day follow-up, 43 patients experienced at least one adverse event and 5 patients died

- None of the patients in the very low risk CSRS category had 30-day serious adverse events

- The risk of adverse events in patients deemed low-risk by clinical judgement was 2%

- The AUC for adverse events for Clinical Judgement was 0.75 (95% CI 0.68 – 0.81)

- The AUC for adverse events for CSRS was 0.68 (95% CI 0.61 – 0.74)

Strengths:

- Multiple centers (both academic and community) were included, offering a greater variety of patient populations and practice environments

- Compared clinical judgement with a risk score to predict 30-day adverse events

- The set of exclusion criteria the authors used was identified by an international panel of syncope researchers and experts. They are also being adopted in international prospective studies on syncope risk stratification in the ED, including the derivation of the CSRS.

- Assessed the presence of all other predictors as done in the CSRS derivation study

- Replaced cardiac vs vasovagal syncope on the CSRS with points based on ED physician’s judgement of short-term adverse effects

Limitations:

- Small sample size (especially when compared to prior validation study where sample size was in the thousands)

- Population of patients was older with higher prevalence of comorbidities

- Approximately 43 patients were lost to follow-up

- Prospective enrollment with retrospective external validation analysis comes with its own limitations on the interpretation of results (ie. already having all the data immediately available, etc)

- Although multicenter, all institutions were in a single country. Unclear how the CSRS does in other countries (outside of Canada and Italy)

- The authors classified patients who left the ED against medical advice to be high risk of adverse events

- Troponins that were not measured were counted as being zero and therefore may have misclassified patients as a lower risk than they actually were.

- Follow-up limited to only a phone interview as opposed to seeing patient and reviewing outpatient records

- Significant amount of variability and subjectivity to “clinical judgement” approach

- The work-up done in this study was different from the original derivation study as many patients were monitored for several hours and thus increasing the number of events recorded

Discussion:

- The patients in this study were older with many more comorbidities than the original CSRS study. In that study, adverse events were found in 3.6% of patients and 9.5% were hospitalized. In this current trial the adverse event rate was 12% and the hospitalization rate was 29%.

- In patients with a CSRS score of <0, the incidence of adverse events was < 2%

- CSRS differs from other risk stratification tools in that it assesses the risk of serious adverse events over 30-days. This improves its clinical relevance as some patients can have adverse events in the first 7 to 30 days after the occurrence of syncope

- The CSRS score was derived in Canadian cohorts. Due to their health system, hospitalization rates after syncope are very low. When applied in a different population in a different health care system (i.e. Italy), CSRS does not fair as well. The patients in this trial were older with a higher prevalence of cardiac disease.

- There may be some possible affirming bias as the patients with adverse events had significantly higher prevalence of heart disease, high or low blood pressure, elevated troponin, abnormal QRS axis, prolonged QT interval and the ED diagnosis of cardiac syncope than those without adverse events

- The authors tried to quantify a subjective factor: clinical judgment or gestalt. A recent multicenter trial showed that no score brings an improvement to early clinical judgement.3 The issue with such claims (in both this paper and that multicenter trial just referenced) is the lack of information about the clinician, their training, and their overall experience

- In addition to the subjective variability that comes with “clinical judgement” the decision to admit to the hospital may not be directly related to the syncopal event itself (ie. social problems, traumas, other conditions, etc)

- It is always worth reiterating that no clinical decision tool should be broadly applied to every patient or used without looking at the entire clinical picture. Clinical decision rules help guide care but don’t dictate care. There is still a place for clinical judgement even in syncope patients

Author’s Conclusions:

- This study represents the first validation analysis of CSRS outside Canada. The overall predictive accuracy of the CSRS is similar to the clinical judgement. However, patients at low risk according to clinical judgement had a lower incidence of adverse events as compared with patients at low risk according to the CSRS. Further studies showing that the adoption of the CSRS improve patients’ outcomes is warranted before its widespread implementation.

Our Conclusion:

- Although patients had lower adverse events with clinical judgement, there was too much variability (and lack of clinician information) compared to the CSRS group. Furthermore, this smaller study with a slightly different population had a work-up that did not precisely reflect what the authors of the CSRS derivation study did however it shows that CSRS did not perform better than clinical judgement. To improve current practice, CSRS would have to be proven to not only have better accuracy than clinical judgement but also improve patient outcomes

Clinical Bottom Line:

- This is the first external validation of the CSRS outside of Canada and shows that it is no better than clinical judgement in its accuracy. Additionally, clinical judgement had a lower incidence of adverse events when compared to low-risk patients via CSRS. This highlights the importance of externally validating clinical decision rules in different populations and across different health systems prior to their implementation and before having them replace clinical judgement

REFERENCES:

- Solbiati M, et al. Multicentre external validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict adverse events and comparison with clinical judgement. Emerg Med J. May 2021 PMID: 34039646

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Multicenter Emergency Department Validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. March 2020. PMID: 32202605

- du Fay de Lavallaz J, et al. Prospective validation of prognostic and diagnostic syncope scores in the emergency department. Int J Cardiol 2018; PMID: 30224031

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @Srrezaie)

The post External Validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.