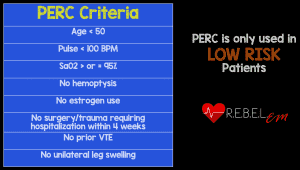

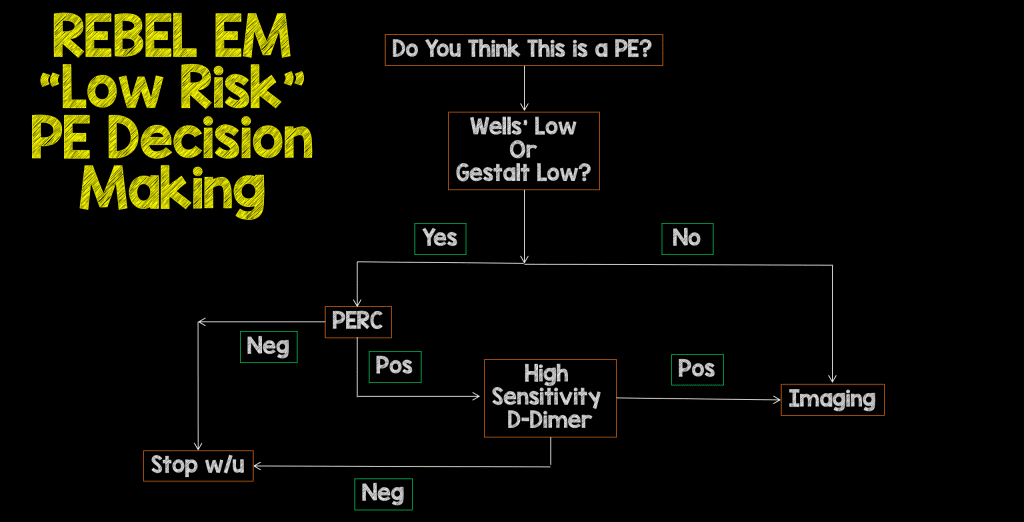

Background: The diagnosis of PE is a tricky thing. We want to limit over-testing patients and therefore, over-diagnosis. On the other hand, we don’t want to limit testing so much that we miss the diagnosis where treatment would make a difference. The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) was created to reduce testing in patients who have a very low probability of PE (i.e. prevalence of <1.8%) in which further testing would not be necessary. There have been many observational trials published on this score but until now there has not been a prospective randomized clinical trial (The PROPER Trial).

Background: The diagnosis of PE is a tricky thing. We want to limit over-testing patients and therefore, over-diagnosis. On the other hand, we don’t want to limit testing so much that we miss the diagnosis where treatment would make a difference. The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) was created to reduce testing in patients who have a very low probability of PE (i.e. prevalence of <1.8%) in which further testing would not be necessary. There have been many observational trials published on this score but until now there has not been a prospective randomized clinical trial (The PROPER Trial).

What They Did:

- Crossover cluster-randomized clinical non-inferiority trial in 14 EDs in France

- These were “low risk” clinical probability of PE patients being assessed for the safety of a PERC-based strategy

- PROPER Trial (PERC Rule to Exclude Pulmonary Embolism in the Emergency Department)

- Two, 6 month periods with a 2 month washout period before crossing over (i.e. half the EDs used PERC & half did not…after 2 months, the EDs that used PERC did not and vice versa):

- Control period (usual care)

- Age adjusted D-dimer testing and if positive à CTPA

- PERC based strategy (intervention period)

- If PERC = 0, then no more testing required

- If PERC ≥ 1 then usual diagnostic strategy applied

- CTPA with emboli were considered positive (i.e. including subsegmental PEs)

- If CTPA inconclusive further testing with VQ scan or Lower let Doppler US was performed

- Control period (usual care)

Outcomes:

- Primary: Occurrence of thromboembolic event during 3 month follow up period, not diagnosed at original inclusion visit

- Secondary:

- Rate of CTPA

- Rate of CTPA adverse events requiring therapeutic intervention within 24hrs

- Median LOS in ED

- Rate of Hospital Admission or Readmission

- Onset of Anticoagulation

- Severe hemorrhage in patients with Anticoagulation

- All Cause Mortality at 3 months

Inclusion:

- All patients with suspicion of PE

- New onset presence or worsening SOB or chest pain and a low clinical probability of PE by physician gestalt as <15%

Exclusion:

- Obvious etiology other than PE (i.e. PTX or ACS)

- Acute severe presentation (Hypotension, SpO2<90%, Respiratory Distress)

- Contraindication to CTPA (Impaired renal function with CrCl <30mL/min, Known allergy to IV contrast)

- Pregnancy

- Inability to be followed up

- Already on anticoagulant therapy

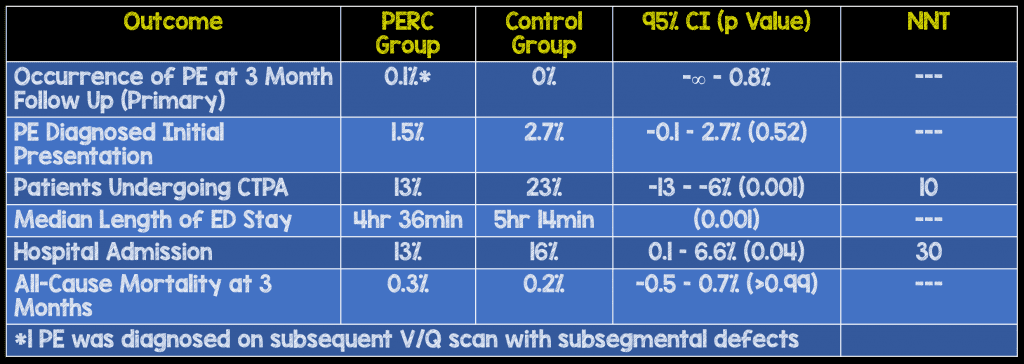

Results:

- 1,916 patients included in analysis

- Mean age: 44 years

- PERC Group: 954 pts – 46 PERC negative patients (5%) underwent d-dimer testing and excluded from the analysis. It is unclear why they had additional testing

- Control Group: 954 pts

- 1,749 patients completed trial

Strengths:

- Multicenter, randomized clinical trial

- All patients instructed to return to the same ED or hospital with recurrent or worsening symptoms to help ensure no loss to follow up

- If unable to get in contact with patient for phone interview, patient’s general practitioner was contacted

- There was an adjudication committee of 3 hemostasis experts, who were blinded to the strategy allocation, that confirmed the occurrence of all suspected PEs and death due to PE

Limitations:

- The prevalence of PE was extremely low (i.e. 2.3%) in this study reducing the ability of this study to detect significant differences between groups

- This is a very young patient population (i.e. age 44 years) which may explain the low prevalence of PE in this study

- CTPA was defined as positive if showed isolated subsegmental PE, which is an issue because many of these could be left untreated

- With a less than 3% maximal failure rate in the control group, the calculated sample size was not accurate and would need to be larger

- Data on eligible patients who were not enrolled in this study were not available (i.e. 46 PERC negative patients who received d-dimer testing) making this a per-protocol analysis and not an intention to treat analysis

- 54 patients were lost to follow up and just a few PEs in these patients would have altered the conclusions of this study

Discussion:

- There were significantly more patients in the control group with a low Wells score of <2: 78% vs 91%

- Obviously, more d-dimer testing and CTPA in the control group: 50% vs 35% and 23% vs 13% respectively

Author Conclusion: “Among very low-risk patients with suspected PE, randomization to a PERC strategy vs conventional strategy did not result in an inferior rate of thromboembolic events over 3 months. These findings support the safety of PERC for very low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department.”

Clinical Take Home Point: In a “low risk” patient population, use of PERC over usual care, was non-inferior in both diagnosis and mortality associated with PE. An added benefit of using PERC over usual care in this study was a 10% decrease in imaging and 40min decrease in ED LOS.

References:

- Freund Y et al. Effect of the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria on Subsequent Thromboembolic Events Among Low-Risk Emergency Department Patients: The PROPER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018. [Link HERE]

- Kline JA. Utiility of a Clinical Prediction Rule to Exclude Pulmonary Embolism Among Low-Risk Emergency Department Patients: Reason to PERC Up. JAMA 2018. [Link HERE]

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- Ryan Radecki at EM Literature of Note: Using PERC & Sending Home Pulmonary Emboli For Fun and Profit

- Rory Spiegel at EMNerd (EMCrit): The Case of the Diagnostic Absurdity

- Scott Aberegg at PulmCCM: Ruling out PE in the ED – Critical Analysis of the PROPER Trial

- Salynn Boyles at PulmCCM: PERC Can Safely Rule Out Pulmonary Embolism in ED Setting

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post Is it PROPER to PERC it Up? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.