Background: Syncope, defined as a transient loss of consciousness with spontaneous and complete recovery to pre-event status, is a common emergency department (ED) presentation. Recently, we have discussed the lack of clinical utility in distinguishing syncope from near-syncope in terms of outcomes. In that discussion, we concluded: “In older adults (> 60 years of age), near-syncope appears to portend an equal risk of death or serious clinical event at 30 days when compared to syncope. These two entities should be considered as one when decisions are made in terms of evaluation in the ED.” While we argue for evaluation and disposition to be the same, we don’t address what the best disposition or plan is. While it is common to admit older patients with syncope/near-syncope from the ED, admission doesn’t inherently yield better outcomes.

Background: Syncope, defined as a transient loss of consciousness with spontaneous and complete recovery to pre-event status, is a common emergency department (ED) presentation. Recently, we have discussed the lack of clinical utility in distinguishing syncope from near-syncope in terms of outcomes. In that discussion, we concluded: “In older adults (> 60 years of age), near-syncope appears to portend an equal risk of death or serious clinical event at 30 days when compared to syncope. These two entities should be considered as one when decisions are made in terms of evaluation in the ED.” While we argue for evaluation and disposition to be the same, we don’t address what the best disposition or plan is. While it is common to admit older patients with syncope/near-syncope from the ED, admission doesn’t inherently yield better outcomes.

Article: Probst MA et al. Clinical Benefit of Hospitalization for Older Adults with Unexplained Syncope: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2019. PMID: 31080027

Clinical Question: Does hospital admission of ED patients >60 years of age with syncope reduce the rate of serious adverse outcomes?

Population: ED patients > 60 years of age who presented to one of 11 EDs with a complaint of syncope or near syncope.

Primary Outcome: Rate of serious adverse events identified within 30 days of index ED visit. Serious adverse events: death from any cause, significant cardiac arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, new diagnosis of structural heart disease, stroke, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, internal hemorrhage or anemia requiring transfusion, recurrent syncope or fall resulting in major traumatic injury, or cardiac intervention

Design: Secondary analysis of data from a multicenter, prospective, observational study of older adults presenting to the ED with syncope or near syncope. Propensity score matching was performed to account for confounding variables

Excluded: Patients whose symptoms were thought to be due to intoxication, seizure, stroke, head trauma or hypoglycemia. Patients were also excluded if a specific intervention was needed to restore consciousness (i.e defibrillation), there was new or worsening confusion or there was an inability to obtain informed consent. The authors also excluded patients with a serious diagnosis identified in the ED (i.e. myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke etc).

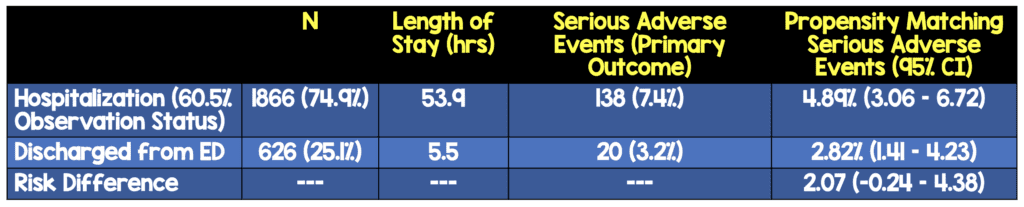

Primary Results:

-

Enrollment numbers

- 6930 eligible patients

-

3686 consented for enrollment

- 105 patients withdrew or lost to follow up

- 1054 (29.4%) had serious diagnosis identified in the ED (and were thus excluded from the analysis)

-

Final cohort: 2492 patients

- Mean age 72.6 years

- 50.8% of patients were women

- 2482 (99.6%) of patients followed up by telephone

- Propensity matched cohort: 1064 patients (532 in each group)

Critical Findings:

-

No statistically significant difference in mortality

- Hospitalized cohort (0.75%; 95% CI 0.21 – 1.91%)

- Discharged cohort (0.56%; 95% CI 0.12 – 1.64%)

- Risk difference of 0.19% (95% CI -1.16 – 0.78%)

-

Death:

- During Hospitalization: 0.1%

- After Hospitalization: 0.7%

- Discharged from ED: 0.5%

-

VF/VT:

- During Hospitalization: 0.4%

- After Hospitalization: 0.2%

- Discharged from ED: 0.0%

Strengths:

- Study asks a clinically important and patient centered question

- Largest prospectively collected cohort of US patients with syncope for this type of analysis

- Detailed propensity matching performed to account for confounders

- For patients with reported ED or hospital visit at an outside facility, records were obtained for medical chart review for those visits

- Performed an additional sensitivity analysis with a more restricted primary outcome (i.e. excluding serious adverse events that occurred after ED evaluation during the index hospitalization) This is important because events that occurred during the index hospitalization may have biased against the hospitalized cohort by increasing the number of adverse events detected in hospitalized patients.

- Follow up with patients was 99.6% with 95 patients requiring chart review, death index query, or both

- After propensity matching, baseline characteristics were equally balanced between groups

Limitations:

- Study is not randomized. Author used propensity matching to help account for confounders but, no statistical manipulation can eliminate this possibility

- Primary outcome was a composite of a large number of outcomes and not all outcomes are equally important (i.e. Occurrence of SVT vs death)

- Findings do not apply to patients < 60 years of age

- Study performed only in US EDs and may not be generalizable outside of the US

- 47% of patients declined participation in the original study introducing the possibility of sampling bias

- Patients followed up by phone which introduces significant issues of recall bias

- No standardized clinical protocols (ie clinical management other than ECG and biomarker testing was left to the discretion of the ED and inpatient providers)

- Sample size was limited to the size of the data set that was collected for the primary analysis so the possibility of type II error is possible (i.e “false negative” finding or conclusion)

Discussion:

- Many studies have focused on determining which group of patients with syncope or near syncope are at an increased risk of serious outcomes. While it’s important to understand whether a patient has a higher or lower risk, it’s more important to know whether we can alter that disease process

- If a specific intervention or, in this case, hospitalization, will lead to improved outcomes, the patient should have this intervention. If that intervention doesn’t improve outcomes, there’s no point in subjecting the patient to it

- This study failed to show a significant clinical benefit for hospitalization for ED patients with unexplained syncope or near syncope in comparison to discharge. However, there are important limitations to consider. There is no data on what diagnostic studies or interventions were performed on patients after admission or after discharge. We don’t know why clinicians chose to hospitalize or discharge and there may be unaccounted for confounders including issues like inability to obtain follow up or social circumstances where hospitalization may be the safer choice.

- This study helps establish the presence of clinical equipoise for hospitalization versus discharge in this group of patients and highlights the need for a well-done randomized trial.

- Unadjusted results demonstrate a greater rate of serious adverse events in hospitalized patients, suggesting that clinicians are good at identifying and appropriately hospitalizing certain higher-risk patients with syncope

- The most common cardiac arrhythmia diagnosed in the hospitalized group was symptomatic supraventricular tachycardia, which does not typically pose a serious risk to patients even if subject to delayed diagnosis

Authors Conclusions:

“In our propensity-matched sample of older adults with unexplained syncope, for those with clinical characteristics similar to that of the discharged cohort, hospitalization was not associated with improvement in 30-day serious adverse event rates.”

Our Conclusions: In this propensity-matched sample of prospectively enrolled patients > 60 years of age with syncope or near-syncope, hospitalization was not associated with a decrease in serious adverse events.

Potential to Impact Current Practice: While a randomized controlled trial is needed, this information should be used by the clinician to tailor the decision for hospitalization versus discharge for the individual patient.

Bottom Line: Hospitalization for patients who are not deemed to be high-risk for a serious cause of syncope, though common in older patients, does not appear to reduce the risk of serious adverse events.

For More on this Topic Checkout:

References:

- Sun BC et al. Predictors of 30-day serious events in older patients with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:769-778. PMID: 19766355

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V et al. Outcomes in presyncope patients: a prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:268-276. PMID: 25182542

- Mendu ML et al. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(14): 1299-1305. PMID: 19636031

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Is There a Benefit to Hospitalization in Syncope? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.