Background Information: The sequential administration of a sedative and neuromuscular blocking agent (NMBA) to facilitate the passage of an endotracheal tube is a common method of intubating in both the emergency department (ED) and intensive care unit (ICU). In fact, 85% of ED intubation and 75% of ICU intubations are performed using RSI. 1 It has been shown that the NMBA not only provides muscle relaxation to improve laryngeal view but has also reduced intubation associated complications, ultimately improving the likelihood of intubation success.2-4 While the early use of a sedative leads to hypoventilation and apnea, the patient has an increased risk of hypoxemia and delaying optimal intubation conditions.1 Use of an NMBA was associated with a lower prevalence of hypoxemia, however the order of its administration before the sedative remains controversial for fear of patient awareness and its use has been limited to the operating room (OR) setting. 1,2 The authors of this study sought to identify whether the order of RSI drugs was associated with increased apnea time during intubation. They defined this interval as the time elapsed from administration of the first RSI drug to the end of a successful first intubation attempt.

Background Information: The sequential administration of a sedative and neuromuscular blocking agent (NMBA) to facilitate the passage of an endotracheal tube is a common method of intubating in both the emergency department (ED) and intensive care unit (ICU). In fact, 85% of ED intubation and 75% of ICU intubations are performed using RSI. 1 It has been shown that the NMBA not only provides muscle relaxation to improve laryngeal view but has also reduced intubation associated complications, ultimately improving the likelihood of intubation success.2-4 While the early use of a sedative leads to hypoventilation and apnea, the patient has an increased risk of hypoxemia and delaying optimal intubation conditions.1 Use of an NMBA was associated with a lower prevalence of hypoxemia, however the order of its administration before the sedative remains controversial for fear of patient awareness and its use has been limited to the operating room (OR) setting. 1,2 The authors of this study sought to identify whether the order of RSI drugs was associated with increased apnea time during intubation. They defined this interval as the time elapsed from administration of the first RSI drug to the end of a successful first intubation attempt.

REBEL Cast Episode 65: Optimal Order of Drug Administration in Rapid Sequence Intubation

What They Did:

- A planned observational secondary analysis of an already completed prospective RCT

- The Intubating physician chose drug, dose and order of sedative vs neuromuscular blocking agent

- They collected the following data points to determine if RSI drug order was associated with apnea time:

-

- Time of drug administration

- When intubation began defined as when the laryngoscope was placed in the mouth

- When intubation ended defined as when the laryngoscope removed from mouth (regardless of whether a bougie or tube passage was attempted).

- Additional airway information to identify difficult airway characteristics, form completed by the intubating physician which included:

-

-

- Body fluid(s) obscuring the laryngeal view

- Airway obstruction or edema

- Obesity

- Short neck

- Small mandible

- Large tongue

- Facial trauma

- Cervical immobilization

-

Inclusion Criteria:

- Adult patients over the age of 18 undergoing endotracheal intubation with a macintosh laryngoscope blade who:

-

- Received both a sedative (ketamine or etomidate) and a neuromuscular blocking agent (succinylcholine or rocuronium) within a 30 second time period

Exclusion Criteria:

- Patients who had a delay of greater than 30 seconds between administration of the NMBA and sedative agent

Prisoners, pregnant women and those with known distortion of upper airway or glottic structures - Other pharmacologic agents used for RSI (ie. propofol, midazolam, atracurium)

- Patients not intubated successfully on the first attempt

Outcomes:

- Primary: Surrogate for apnea time: Time elapsed from administration of first RSI drug to removal of laryngoscope blade

-

Secondary:

- First intubation attempt duration

- First attempt success

- Hypoxemia

Results:

- 562 of the 757 patients enrolled were eligible for inclusion in the main analysis.

- 153 patients (27%) were administered the sedative agent first

- 409 patients (73%) were administered the neuromuscular blocking agent first

- Not viewing the video screen and more operator experience were associated with shorter intubation times

- Rocuronium use and worsening laryngoscopic view was associated with longer intubation times

Critical Results:

- Administration of the NMBA before the sedative was associated with a reduction in apnea time of 6 seconds (95% CI 0-11 seconds)

- Unadjusted analysis of secondary outcomes were not significantly different

Strengths:

- Utilized both the most commonly used sedatives and most commonly used NBMAs

- Patients were consecutively enrolled and not a convenience sample

- Performed a multivariable analysis in an attempt to control for potential confounding

- Other independent variables outside of RSI that may affect intubation time were selected a priori

- Authors performed the following two sensitivity analyses to account for the patients excluded in the main analysis:

- First intubation attempt success

- RSI drugs not administered within 30 seconds of one another

Limitations:

- Excluded infrequently used RSI medications such as propofol and midazolam may have been a negative confounding variable

- Only patients who were intubated successfully on the first attempt were analyzed

- No prior estimates of how RSI medications affect intubation time exists and therefore the authors used the sample size from the parent trial

- Small sample size of patients who had the sedative agent administered first thus questioning whether the 6 second difference between the true groups is accurate

- It is important to consider that the authors self-defined surrogate for apnea time and its presentation in this analysis may differ from the actual effects of sedatives on ventilatory effort.

- The authors did not record patient memories of the intubation and thus by giving the paralytic first, intubation could have been initiated before complete muscle relaxation. The bias towards a faster intubation time particularly exists without knowing if the NMBA group had any adverse effects such as awareness of paralysis during the intubation as a whole.

- Variations of failed and successful intubation attempts may also be a confounding factor

- 95% of intubations were done with visual laryngoscopy using a Macintosh blade which may affect generalizability and its external validity.

- Given that >70% of the intubations performed in this study were with the NMBA being administered first, the findings of this study may not be generalizable to all settings as more physicians appeared to be comfortable giving the paralytic before the sedative.

- Lastly, the authors definition of apnea time may vary depending the actual sedative effects on ventilatory effort.

Discussion:

- The authors place a significant emphasis on how the administration of the NMBA first is associated with a 6 second reduction in apnea time, however it is important to remember that the sample size between the sedative and NMBA group was disproportionately favoring the latter.

- This reduction in time using NMBAs should be confirmed and validated in future studies to identify if clinically significant for critically ill patients (ie. asthmatics, acute respiratory distress syndrome and severe metabolic acidosis).

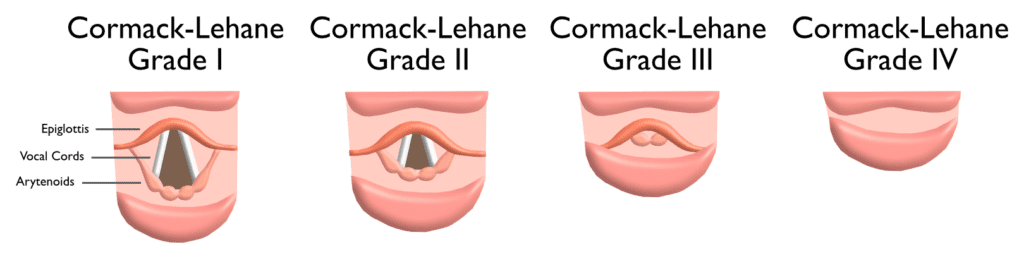

- It is worth noting that 99% of intubations used etomidate as their pre-intubation sedative and approximately 60% used succinylcholine as their paralytic agent and 76% of intubations had a Grade 1 Cormack-Lehane Laryngeal view while approximately 6% had Grade 3 or 4 views (see Figure 1) thus potentially affecting their intubation success.

- Although rare, an important consideration which the study did not evaluate for, is the delay in administration of the sedative from factors like loss of vascular access or other staff/departmental distractions.

- While there was a baseline difference in the median oxygen saturation of <90% favoring the NBMA group, without having a more accurate comparison of the effects of NMBAs and sedatives on apnea time (which includes some measure of the patient’s awareness), it is difficult to justify selecting which of the two drugs should be administered first.

- The authors describe the “timing principle” used in the operating room, where an NMBA is administered first followed by a sedative when weakness or paralysis is detected. 6-8 This is difficult to apply to intubations in the emergency room for two reasons. First, the extended delay between administration of the two drugs no longer qualifies this as RSI. Second, intubations in the OR are often in much more controlled and predictable settings.

- Lastly, future studies should consider evaluating the intubator’s experience in addition to the order of RSI drugs on first pass success as this may be more of a significant contributing factor than just the RSI drug order alone.

Author’s Conclusions:

- Administration of either the neuromuscular blocking or sedative agent first are both acceptable. Administering the neuromuscular blocking agent first may result in modestly faster time to intubation. For now, it is reasonable for physicians to continue performing RSI in the way they are most comfortable with. If future research determines that the order of medication administration is not associated with awareness of neuromuscular blockade, administration of the neuromuscular blocking agent first may be a logical default administration method to attempt to minimize apnea time during intubation

Our Conclusion:

- This study does an adequate job at opening the discussion of whether or not the order of RSI medications affects apnea time. Given the disproportionate sample size favoring NMBA administration, the reduction of apnea time by 6 seconds when using NMBA requires a more accurate comparison and validation.

Clinical Bottom Line:

- Future research is needed to better compare the effects of NMBAs and sedatives on apnea time and whether the administration of NMBAs first has any effect on patient awareness. Until then, we agree with the author’s statement that emergency physicians should continue to perform RSI in the way they are comfortable with.

Figure 1: Breakdown of the four Cormack-Lehane Grades for laryngeal view during direct laryngoscopy

REFERENCES:

- Driver B, et al. Drug order in rapid sequence intubation. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2019. PMID: 30834639

- Wilcox SR, et al. Neuromuscular blocking agent administration for emergent tracheal intubation is associated with decreased prevalence of procedure-related complications. Crit Care Med. 2012 PMID: 22610185

- Li J, et al. Complications of emergency intubation with and without paralysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1999 PMID: 10102312

- Lundstrøm LH, et al. Avoidance vs use of neuromuscular blocking agent for improving conditions during tracheal intubation: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2017 PMID: 28513831

- Nelson JM, et al. Rocuronium versus succinylcholine for rapid-sequence induction using a variation of the timing principle. J Clin Anesth. 1997 PMID: 9195356

- Sieber TJ, et al. Tracheal intubation with rocuronium using the “timing principle.” Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1998 PMID: 9585312

- Koh KF, et al. Rapid tracheal intubation with atracurium: the timing principle. Can J Anaesth. 1994 PMID: 7923516

- Chatrath V, et al. Comparison of intubating conditions of rocuronium bromide and vecuronium bromide with succinylcholine using “timing principle.” J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010 PMID: 21547177

- Airway Management | MD Nexus. Mdnxs.com. Published 2019 Link here

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- PulmCrit (EMCrit): Rocketamine vs. Keturonium for Rapid Sequence Intubation

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Cast Episode 65: Optimal Order of Drug Administration in Rapid Sequence Intubation appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.