Take Home Points

Take Home Points

- Compartment syndrome is a life and limb threatening emergency that requires early recognition, prompt diagnosis and immediate management with fasciotomy

- While clinical evaluation is flawed, pain out of proportion to injury and pain with passive stretch of muscles within the compartment are the best screening tools.

- Do not wait for the development of pallor, absence of pulse or paralysis to consult surgery. These are late findings that may only arise once the limb is non-salvageable.

- In unconscious patients, there should be a low threshold to measure compartment pressure in patients who are at risk as clinical signs cannot be evaluated

- When measuring compartment pressures, look for an absolute pressure > 30 mm Hg and perfusion pressure (DBP – compartment pressure) of < 30 mm Hg. All patients with a clinical suspicion and normal pressures should have repeat pressures measured.

REBEL Core Cast 80.0 – Compartment Syndrome

Definition: Increased pressure within a closed space that compromises circulation and, thus, function of the tissues (i.e. muscle, nerve, bone) within the space. Sequelae include neurological deficit, Volkmann’s contracture, limb amputation and crush syndrome.

Epidemiology:

- Most commonly seen after a traumatic injury to an extremity

- Can occur in the absence of fracture

- Occur in 1-10% of tibial fractures (Elliott 2003)

- 75% of traumatic compartment syndrome accounted for by long-bone fractures (Carter 2013)

- Most common sites: lower leg, upper leg, forearm, gluteal/thigh and hand

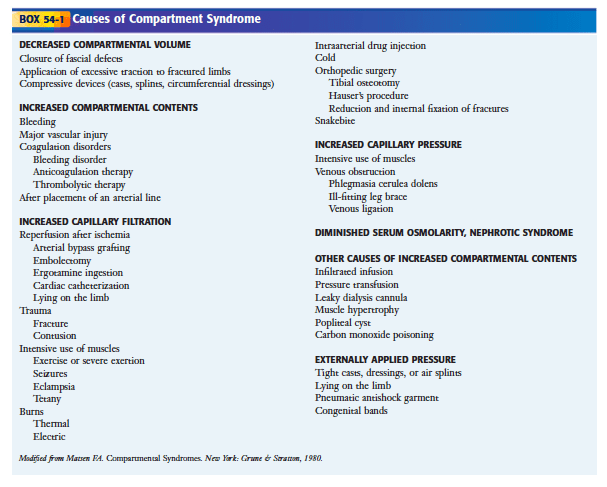

Causes:

- Fracture

- Bleeding into compartment (i.e. vascular injury)

- External compression (i.e. cast, crush injury)

- Iatrogenic (infiltration of IV infusion, surgical complication)

Pathophysiology:

- Increased compartment pressure -> increased venous pressure -> compromised local circulation and hypoxia

- Three general etiologies

- Increased compartment contents (bleeding, infiltrated infusion)

- Decreased compartment volume

- External pressure

- Tissue threshold for ischemia

- Muscle – 4 hours

- Nerve – 8 hours

- Fat – 12 hours

- Skin – 24 hours

- Bone – 72-96 hours

Signs + Symptoms:

- Classic “5Ps”

- Pain disproportionate to injury or exam findings (hallmark finding)

- Paresthesias

- Pallor

- Pulselessness

- Paralysis

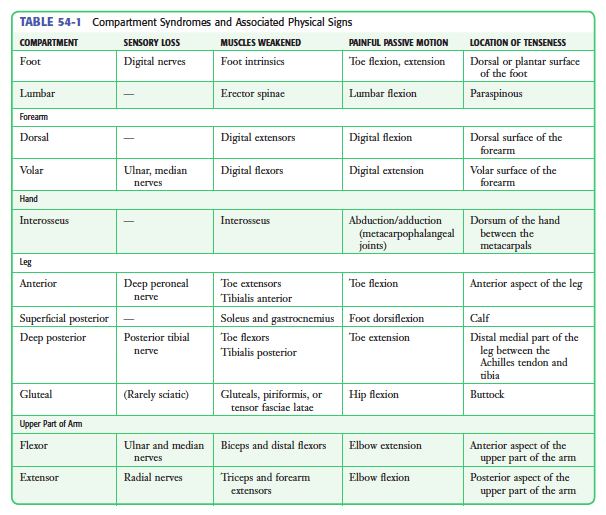

- Pain with passive stretch of muscles within specific compartment (see table from Roberts and Hedges)

- Limitations of examination

- Examination only potentially useful in patients who are alert. Often, patients at risk for compartment syndrome have polysystem trauma and may be obtunded.

- Pallor, pulselessness and paralysis are late findings

- Motor weakness evaluation may be limited by pain (Frink 2010)

- A review article in 2013 looks at all of the above clinical signs and symptoms and concludes that there is limited quality investigations to determine the performance of any of them (Nelson 2013).

Diagnosis

- Unconscious patient

- Signs and symptoms will not be evaluable in this group

- If the patient has a high-risk injury for compartment syndrome (tibial fracture, crush injury etc) direct compartment pressure measurement should be performed

- Consider repeat measurement every 4 hours as compartment syndrome is a progressive disease (Wall 2010)

- Compartment Pressure Measurement

-

Diagnostic Threshold

- Absolute pressure > 30 mm Hg

- Perfusion pressure (DBP – Compartment Pressure): < 30 mm Hg

- Pressure Measurement Pearls

- Single compartment pressure measurements have been shown to have low specificity leading to over-diagnosis and over-treatment (Nelson 2013, Whitney 2014)

- Serial Pressure Measurement: Patents with high clinical suspicion of compartment syndrome but normal initial measurements should have serial measurements performed

- Continuous Pressure Monitoring: A single study out of Scotland demonstrated a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 98% for continuous compartment pressure monitoring (McQueen 2013)

- At risk extremities have multiple compartments. It is critical to measure the compartment pressure in every compartment.

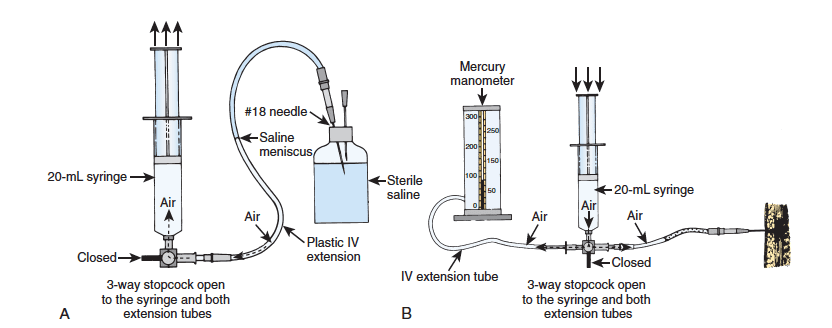

- Mercury Manometer System (Whitesides method)

- In vitro, measurements found to be both inaccurate and inconsistent (Ullasz 2003, Boody 2005)

- Technique overestimates pressure leading to increased false positives (Boody 2005)

- Can be assembled from teams typically found in the ED

-

Diagnostic Threshold

-

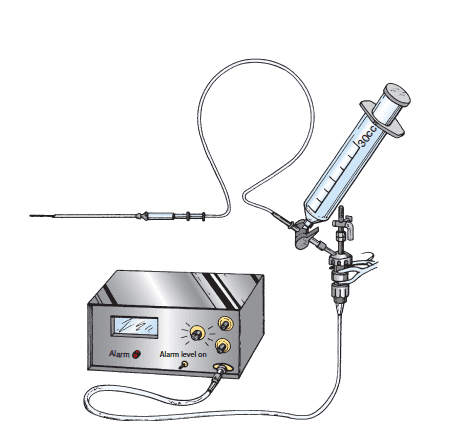

- Arterial Line System

- In vitro studies demonstrate excellent correlation between actual pressure and measured pressure by this system (Boody 2005)

- Can be assembled from teams typically found in the ED

- Arterial Line System

-

Arterial Line System

(Roberts + Hedges)- Styker® device

- In vitro studies demonstrate excellent correlation between actual pressure and measured pressure by this system (Boody 2005)

- Video reviewing setup and use of Styker® device can be found here

- Styker® device

Management:

Basics:

- Immediate surgical consultation

- Patient with compartment syndrome often have polytrauma so make sure to perform a complete trauma evaluation.

- Restore circulating volume to increase perfusion to the extremity

- Remove any external compressive devices (casts, splints, tourniquets). Removal of casts (or bi-valving) can reduce pressure by up to 65-90%

- Maintain limb at level of heart or keep slightly dependent (maximize arterial perfusion without decreasing venous drainage)

- Don’t forget to look for concomitant rhabdomyolysis and crush syndrome (reperfusion injury occurring after traumatic rhabdomyolysis characterized by extensive muscle death, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis and myoglobinuric acute renal failure)

Fasciotomy

- Optimal therapeutic approach is immediate fasciotomy in the operating room. Delay of surgical intervention can result in irreversible muscle damage, nerve death and bone infarction

- Indications (Wall 2010)

- Clinical signs of acute compartment syndrome

- Absolute compartment pressure > 30 mm Hg

- Perfusion pressure < 30 mm Hg

- Regardless of the specific compartment involved, all compartments in the affected extremity should have fasciotomy performed

Take Home Points

- Compartment syndrome is a life and limb threatening emergency that requires early recognition, prompt diagnosis and immediate management with fasciotomy

- While clinical evaluation is flawed, pain out of proportion to injury and pain with passive stretch of muscles within the compartment are the best screening tools.

- Do not wait for the development of pallor, absence of pulse or paralysis to consult surgery. These are late findings that may only arise once the limb is non-salvageable.

- In unconscious patients, there should be a low threshold to measure compartment pressure in patients who are at risk as clinical signs cannot be evaluated

- When measuring compartment pressures, look for an absolute pressure > 30 mm Hg and perfusion pressure (DBP – compartment pressure) of < 30 mm Hg. All patients with a clinical suspicion and normal pressures should have repeat pressures measured.

Read More:

- Plastsurgproj’s YouTube Channel: Compartment pressure measurement

References:

- Elliott KG, Johnstone AJ. Diagnosing acute compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg. – British Volume 2003; 85: 625–32.

- Carter MA: Compartment Syndrome Evaluation in Roberts JR, Hedges JR, Custalow CB, et al (eds): Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine, ed 6. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2013, Ch 54:p 1095-1124.

- Frink M et al. Compartment syndrome of the lower leg and foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:940–50. PMID: 19472025

- Nelson JA. Compartment pressure measurements have poor specificity for compartment syndrome in the traumatized limb. J Emerg Med 2013; 44(5): 1039-44. PMID: 23321294

- Wall CJ et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of acute limb compartment syndrome following trauma. ANZ J Surg 2010; 80: 151-6. PMID: 20575916

- Whitney A et al. Do one-time intracompartmental pressure measurements have a high false-positive rate in diagnosing compartment syndrome. Acute Care Surg 2014; 76: 479-83. PMID: 24458053

- McQueen MM et al. The estimated sensitivity and specificity of compartment pressure monitoring for actue compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95: 673-7. PMID: 23595064

- Ullasz A et al. Comparing the methods of measuring compartment pressures in acute compartment syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 2003; 21: 143-5. PMID: 12671817

- Boody AR, Wongworawat MD. Accuracy in the measurement of compartment pressures: a comparison of three commonly used devices. J Bone Joint Surg 2005; 87: 2415-2422. PMID: 16264116

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Core Cast 80.0 – Compartment Syndrome appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.