Background: Chest pain is a common chief complaint the Emergency Department, and the differential diagnosis includes life-threatening conditions from several organ systems including cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal, in addition to more benign etiologies. Historically, despite most patients not having acute coronary syndrome, there is still a high rate of medical admissions in patients with chest pain. The advent of accelerated diagnostic protocols has aided in guiding clinicians with decision making and disposition of these patients. This study aimed to address the question of whether or not an emergency medicine physician’s clinical gestalt would be sufficient to rule in or rule out acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Several studies have addressed this question with conflicting results.

Background: Chest pain is a common chief complaint the Emergency Department, and the differential diagnosis includes life-threatening conditions from several organ systems including cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal, in addition to more benign etiologies. Historically, despite most patients not having acute coronary syndrome, there is still a high rate of medical admissions in patients with chest pain. The advent of accelerated diagnostic protocols has aided in guiding clinicians with decision making and disposition of these patients. This study aimed to address the question of whether or not an emergency medicine physician’s clinical gestalt would be sufficient to rule in or rule out acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Several studies have addressed this question with conflicting results.

Given the high morbidity and mortality of acute coronary syndrome, emergency medicine physicians focus their clinical decision making on decreasing type II errors, i.e., false negatives. In clinical practice, this means having a low rule-out rate based on physician gestalt; in other words, most patients with chest pain presenting to the Emergency Department will have testing including an EKG and troponin level even for patients for whom the physicians have a low clinical suspicion for ACS.

Article: Oliver G et al. Can Emergency Physician Gestalt “Rule In” or “Rule Out” Acute Coronary Syndrome: Validation in a Multi-Center Prospective Diagnostic Cohort Study. Acad Emerg Med 2019. PMID: 31338902

What They Did: This was a pre-planned secondary analysis of the BEST (Bedside Evaluation of Sensitive Troponin) study. The BEST study was a prospective multicenter study in the United Kingdom that included 1,391 patients presenting with symptoms concerning for ACS. At the time of the initial patient assessment, the emergency medicine physician was provided with the initial EKG, initial troponin (if available), patient demographic information, and the patient’s past medical history. The physician then rated his or her clinical gestalt using a five-point Likert scale from “definitely not ACS” to “definitely ACS”.

All patients received serial troponin testing, but the timing depended on the type of assay being used:

- 3hrs for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays

- At least 6hrs for contemporary assays

The patients’ outcomes were followed at 30 days. The patients were contacted by telephone, email, letter, in person, or with the patients’ primary care physicians.

Outcomes:

- Primary: ACS diagnosis (either acute myocardial infarction or major adverse cardiac event at 30 days). Major adverse cardiac event was defined as death from any cause, coronary revascularization, or acute myocardial infarction. Acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed based on the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.

Inclusion Criteria:

- ≥18 years of age

- Presenting to the Emergency Department with symptoms where ACS was suspected (including chest pain or discomfort where no other cause was apparent)

- Onset of chest pain within the past 12 hours

Exclusion Criteria:

- Patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- Onset of chest pain more than 12 hours ago

- Patients with non-ACS chief complaints whose hospital admissions were not due to ACS

- Patients unable to give consent

Baseline Characteristics:

- The patients were 64% male

- The average age of the participants was 58.7 years (standard deviation of 15.4)

- 50% had hypertension, 38% had hyperlipidemia, 28% had a previous MI, 28% had previous angina, 19% had type II diabetes mellitus, 20% were current smokers

Results:

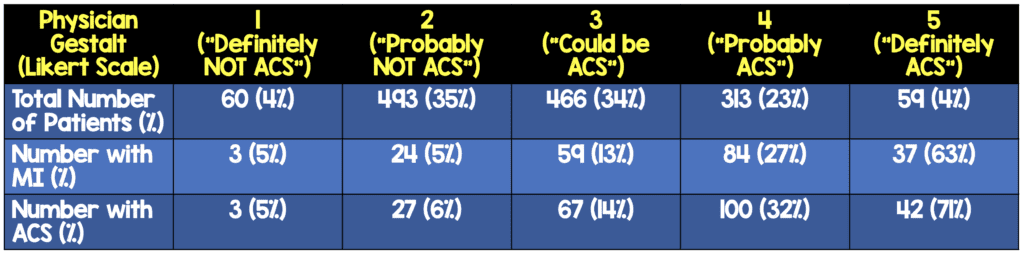

- 1,391 patients total

- 240 (17.3%) had ACS

- 207 (14.9%) were diagnosed with MI

- 344 (24.7%) had an initial troponin greater than the 99th percentile

- Overall gestalt had fair diagnostic accuracy: C-Statistic 0.75 (95% CI 0.72 – 0.79)

- Separate calculations of sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, and positive predictive value were calculated for multiple scenarios of clinician gestalt judgments including with and without troponin, with and without EKG were done based on which of these data points the physicians had available.

“Rule Out” Strategy:

-

Gestalt (NO ECG or Initial Troponin):

- “Definitely Not” ACS: Sensitivity 98.3% NPV 95.0%

- “Definitely Not” or “Probably Not” ACS: Sensitivity 87.8% & NPV 94.8%

-

Gestalt + ECG (No Initial Troponin):

- “Definitely Not” ACS = Sensitivity 98.8% & NPV 95.0%

- “Definitely Not” or “Probably Not” ACS = Sensitivity 87.8% & NPV 94.8%

-

Gestalt + ECG + Initial Troponin:

- “Definitely Not” ACS = Sensitivity 100% & NPV 100%

- “Definitely Not” or “Probably Not” ACS: Sensitivity 86.2% & NPV 99.2%

“Rule In” Strategy:

-

Gestalt (NO ECG or Initial Troponin):

- “Definitely” ACS: Specificity 98.5% & PPV: 71.2%

- “Definitely” or Probably” ACS: Specificity 79.8% & PPV 37.7%

-

Gestalt + ECG (NO Initial Troponin):

- “Definitely” ACS: Specificity 97.9% & PPV: 95.0%

- “Definitely” or Probably” ACS: Specificity 44.7% & PPV 62.3%

-

Gestalt + ECG + Initial Troponin:

- “Definitely” ACS: Specificity 90.0% & PPV: 94.1%

- “Definitely” or Probably” ACS: Specificity 50.0% & PPV 87.8%

Strengths:

- The analysis was pre-specified including outcomes

- Outcomes were adjudicated by two investigators that were blinded to each other’s comments and to clinician gestalt

- The limitations section of the paper discusses the limitations candidly

Limitations:

- 222 patients were excluded from the BEST study’s sample of 1,613 patients due to missing data

- Only 4% of patients were determined to be at each end of the Likert scale (“Definitely not ACS” or “Definitely ACS”).

- One third of patients with acute MI experienced no chest pain before or during admission, which this study did not include. (Women and patients with diabetes are more likely to experience atypical symptoms.)

- The study design has the possibility of sampling bias. As the authors note, the patients selected for the study already had to be selected for inclusion based on suspected cardiac origin of chest pain.

- Clinicians were not blinded to initial ECG and initial cardiac troponin results on initial evaluation, which biases gestalt in the calculations that include EKG and/or initial troponin but also means this study does not truly assess diagnostic accuracy of gestalt of chest pain in isolation.

- The accuracy of clinician recording the presence of acute ischemic ECG features was not validated.

- 30 day follow up was conducted by telephone, email, letter, or in person. This could lead to recall bias.

Discussion:

This study aimed to answer whether a physician’s clinical gestalt as defined in the study was accurate for either ruling in or ruling out ACS. Clinicians were unblinded to both the ECG and initial cardiac troponin results if they were available at the time of the initial assessment but were blinded to serial cardiac troponin results and final patient outcomes. This study was fundamentally estimating the risk of a positive second troponin or risk of MACE at 30 days in a population of patients already stratified as having suspected cardiac chest pain.

The positive predictive value of a physician’s clinical gestalt as a rule in for ACS was very low at 38%. The negative predictive value of a physician’s clinical gestalt as a rule out for ACS was higher at 95%. Sampling bias could skew the results given that the sample was already selected for suspected cardiac chest pain (based on the American Heart Association’s case definition for ACS.

Because emergency medicine physicians focus on reducing false negatives, likely in clinical practice physicians would be ordering at a minimum an EKG and troponin level in most patients with chest pain. This study did not establish how a Likert rating would translate into a decision to obtain further testing. In clinical practice, would physicians decide not to obtain a cardiac workup even in patients for whom the physicians would give a gestalt rating of 1, i.e., definitely not ACS? The study concludes that for these cases determined to be “definitely not ACS” based on gestalt, physicians would miss 5% of cases that in fact were ACS. However, given the likelihood of sampling bias for patients already suspected of having ACS, the false negatives may actually be lower.

Authors’ Conclusion: “Clinician gestalt is not sufficiently accurate or safe to either “rule in” or “rule out” ACS as a decision-making strategy. This study will enable emergency physicians to understand the limitations of our clinical judgement.”

Clinical Take Home Point: In this study, clinician gestalt was not safe to rule out ACS; however, further research is necessary to more conclusively determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of clinical gestalt. Furthermore, this study was fundamentally estimating the risk of a positive second troponin or risk of MACE at 30 days in a population of patients already stratified as having suspected cardiac chest pain.

References:

- Oliver G et al. Can Emergency Physician Gestalt “Rule In” or “Rule Out” Acute Coronary Syndrome: Validation in a Multi-Center Prospective Diagnostic Cohort Study. Acad Emerg Med PMID: 31338902

- Mokhtari A et al. Diagnostic Values of Chest Pain History, ECG, Troponin and Clinical Gestalt in Patients with Chest Pain and Potential Acute Coronary Syndrome Assessed in the Emergency Department. Springerplus 2015. PMID: 25992314

- Body R et al. Can Emergency Physicians ‘Rule In’ and ‘Rule Out’ Acute Myocardial Infarction with Clinical Judgement? Emerg Med J PMID: 25016388

- Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics, and Mortality Among Patients With Myocardial Infarction Presenting Without Chest Pain. JAMA2000. 10866870

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- First10EM: Physician Gestalt for ACS (Oliver 2019)

- EMLitofNote: If You Guessed “Definitely Not ACS”…

- JournalFeed: Can Gestalt Rule In or Rule Out ACS?

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Can Emergency Physicians Use Clinical Gestalt to Predict Acute Coronary Syndrome? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.