Background Information: Delirium is defined as an acute disorder of consciousness which can occur in up to 80% of mechanically ventilated ICU patients.1-5 This acute cognitive dysfunction is associated with prolonged hospital stay, increased mortality, longer periods of mechanical ventilation and long-term cognitive impairment compared to patients without delirium.4-8 Haloperidol, remains one of the most commonly used typical antipsychotics used to treat delirium internationally and within the United States.9,10 The Society of Critical Care Medicine’s recent guidelines do not suggest the use of Haloperidol in the prevention or treatment of delirium11 and understandably so as two randomized trials showed no reduction in duration of ICU delirium.5,12 Alternative therapies for delirium include atypical antipsychotics such as ziprasidone, however the literature shows conflicting evidence, with one study showing a benefit and another showing no effect.5,13 The authors of this study sought to examine the effects of these two treatments in a large multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Background Information: Delirium is defined as an acute disorder of consciousness which can occur in up to 80% of mechanically ventilated ICU patients.1-5 This acute cognitive dysfunction is associated with prolonged hospital stay, increased mortality, longer periods of mechanical ventilation and long-term cognitive impairment compared to patients without delirium.4-8 Haloperidol, remains one of the most commonly used typical antipsychotics used to treat delirium internationally and within the United States.9,10 The Society of Critical Care Medicine’s recent guidelines do not suggest the use of Haloperidol in the prevention or treatment of delirium11 and understandably so as two randomized trials showed no reduction in duration of ICU delirium.5,12 Alternative therapies for delirium include atypical antipsychotics such as ziprasidone, however the literature shows conflicting evidence, with one study showing a benefit and another showing no effect.5,13 The authors of this study sought to examine the effects of these two treatments in a large multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Clinical Question: Does the use of typical and atypical antipsychotic medications result in improved outcomes and a shorter duration of delirium in ICU patients with respiratory failure or shock compared to placebo?

What They Did:

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at 16 medical centers in the United States.

- Patients who met the inclusion criteria below who had delirium present at the time of informed consent or 5 days following consent, were randomly assigned to receive doses of placebo, haloperidol, or ziprasidone.

- Patients over the age of 70 years old started at half the dose of each medication compared to those under the age of 70 years old. Every 12 hours, the volume and dose of both the trial drug and placebo were doubled if the patient had delirium and had not yet received the maximum dose

- Medications were permanently discontinued if any of the following occurred:

- Torsades de pointes

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Drug reaction with eosinophila

- New on-set coma due to structural brain disease

- Any life-threatening even that was related to the intervention as determined by an independent data and safety monitoring board

Outcomes:

- Primary end point was:

- Number of days a patient was alive and free from both delirium and coma during 14-day intervention period

- Secondary Outcomes (included following 48hr period afterwards):

- Duration of delirium

- Time to freedom from mechanical ventilation

- Time to final successful ICU discharged

- Time to ICU readmission

- Time to successful hospital discharge

- 30-day and 90-day survival

- Safety end-points included:

- Incidence of torsades de pointes

- Incidence of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and extrapyramidal symptoms (measured using modified Simpson-Angus Scale)

Inclusion Criteria:

- Patients over the age of 18 years old

- Medical or surgical ICU patients receiving any of the following treatments:

- Invasive or non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

- Vasopressor support

- Intra-aortic balloon pump

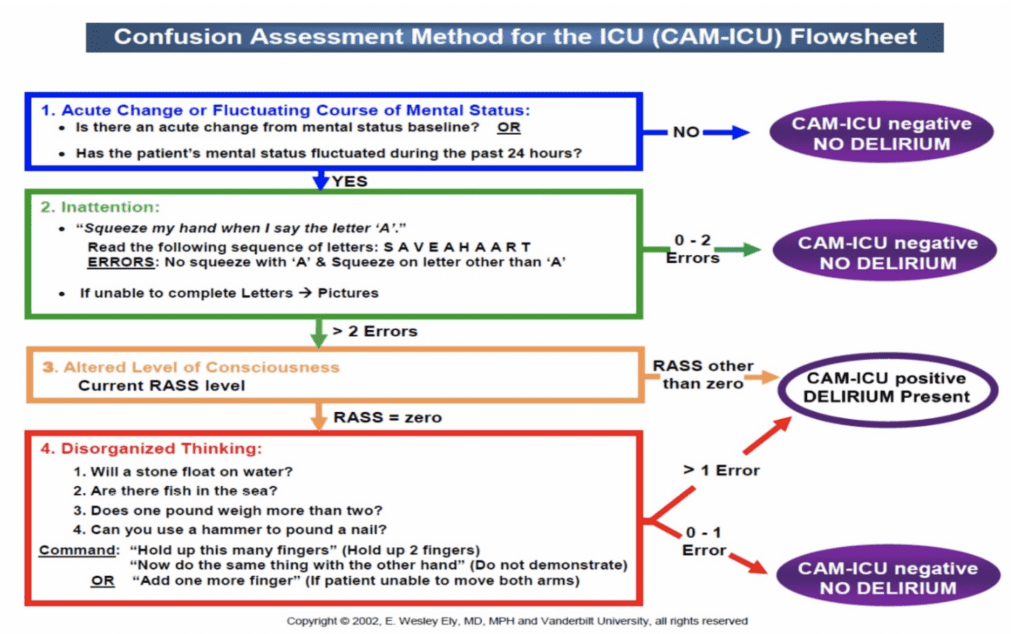

- Patients with delirium as detected using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) validation tool (See Figure 1).14

Figure 1:The widely accepted Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) used to detect acute changes or fluctuating mental status.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Patients with severe cognitive impairment at baseline (as determined by medical record review) and a score of greater than 4.5 on the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE).15

- Patients at high risk for medication side effects due to the following:

- Pregnancy

- Breast-feeding

- History of torsades de pointes

- QT prolongation, greater than 550 msec on a 12-Lead EKG

- History of neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Allergy to haloperidol or ziprasidone

- Were receiving ongoing treatment with an antipsychotic medication

- Were in a moribund state

- Had rapidly resolving organ failure

- Were incarcerated

- Blind, deaf, mute or unable to understand English

- Inability to obtain consent within a given time period for comatose and non-comatose patients

Results:

- 20,914 screened, 16,306 (78%) met exclusion criteria of the 4608 patients remaining, 3425 (74%) declined to participate.

- 571 (48%) out of the remaining 1183 did not develop delirium before leaving the ICU and 46 (4%) met exclusion criteria upon further assessment.

- Leaving 566 (48%) patients who had delirium to be randomly assigned to one of the three trial groups.

- 89% of the patients had hypoactive delirium while 11% had hyperactive delirium.

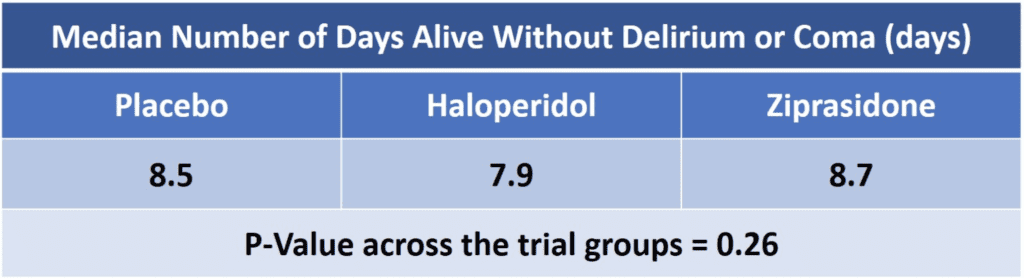

Critical Results:

- Furthermore, the authors found no difference in days to freedom from mechanical ventilation, ICU discharge, ICU readmission, hospital discharge, death at 30 days or death at 90 days using either of these medications when compared to placebo.

- Prolongation of the corrected QT interval was more common in the ziprasidone group than in the haloperidol or placebo group.

Strengths:

- Randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled multi-center study

- The authors chose to study typical and atypical antipsychotics, two commonly used drug categories to treat delirium.

- Broad inclusion criteria to enhance generalizability

- Adherence to all five components of the Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium monitoring/management and Early exercise/mobility (ABCDE) treatment bundle among providers was >88%

- Assess, prevent, and manage pain

- Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials

- Choice of analgesia and sedation

- Delirium management

- Early mobility and exercise1

- Large sample size even after exclusion criteria and declining to participate by patient’s authorized representatives.

- Use of validated instruments administered by trained personnel. Ex. Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), CAM, IQCODE, and Simpson-Angus Scale)

- Well defined and numerous efficacy end-points that are directly applicable to any critical care clinician

- Closely monitored and clearly stated safety endpoints such as:

- Withholding trial drug due to suspected neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- A patient in each group having the trial drug withheld because of extrapyramidal symptoms

- Withholding trial drug in one patient from the haloperidol group due to dystonia

Limitations:

- Trial was only powered to detect a 2-day difference between the groups, therefore it is unknown if there was any effect on less than 2 days.

- Patients were evaluated only twice a day, which may have not been enough to accurately assess the effects of the study’s intervention

- 90% of patients were receiving GABA receptor agonists (such as propofol or benzos) for sedation and thus increasing their risk for delirium during critical illness.16

- Generalized inclusion criteria also serves to create a heterogenous group of patients enrolled thus possibly invalidating the authors non-conclusive findings

- They recognize this by giving the example of patients with alcohol withdrawal who may in fact benefit from antipsychotic treatment.

- Acknowledged that they used a high-dose of haloperidol justifying it by attempting to avoid deleterious effects on cognition. However, they failed to explain why a smaller maximum dose was not utilized.

Discussion:

- In an international survey of over 1500 intensivists, 65% report treating ICU delirium with haloperidol while 53% report treating delirium with atypical antipsychotic medications.10

- Results of their trial were similar to two earlier placebo-controlled studies examining the use of haloperidol in ICU patients with delirium:

-

Modifying the Incidence of Delirium (MIND) Trial

- 101 mechanically ventilated patients randomly received enteral haloperidol, ziprasidone, or placebo.

- Result was no significant difference in days alive without delirium or coma.5

- Haloperidol Effectiveness in ICU Delirium (Hope-ICU) Trial

- 142 mechanically ventilated patients randomly received IV haloperidol or placebo.

- There were fewer days of agitated delirium in the patients who received haloperidol.

- Overall there was no effect on days alive without delirium or coma.12

- Authors theorize the following two reasons for the lack of effectiveness of these interventions on delirium

- Increased dopamine signaling being the major mechanism of brain dysfunction and ultimately delirium may not play a major role of delirium specifically in the setting of critical illness

- Delirium in ICU patients may be multifactorial and contributed to by the presence of GABA agonists sedatives such as propofol.16This especially may have been the case given the majority of the sample size had hypoactive delirium.

- The stark difference in the two types of delirium in the study’s patient population is worth noting. 504 out of 566 (89%) patients had hypoactive delirium.Hypoactive delirium is associated with poorer outcomes, increased mortality, and admission to longer term care.17This type of delirium is often missed due to its fluctuating condition or inability of the withdrawn patient to alert a care provider. The inability of the provider to capture the shift from baseline mental status also serves as a barrier, as a longitudinal overview of the patient’s care is typically required to make the diagnosis.

- Anti-psychotic use should be limited to the following:

- Quetiapine:May help patients who have insomnia and are high risk for delirium better regulate their sleep-wake cycles.

- Haloperidol or Olanzapine: These still have an important role in patientswith acute uncontrolled agitation

- Quetiapine or Olanzapine: Use at lower doses in difficult to sedate patients to optimize the anti-histamine effects, rather than their dopaminergic activity, and to have them function “non-deleriogenic sedatives”.18

Author’s Conclusions:

- There is no evidence that the use of haloperidol (up to 20mg daily) or ziprasidone (up to 40mg daily) had an effect on duration of delirium and coma in ICU patients with acute respiratory failure or shock.

Our Conclusion:

- This double-blinded, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study had a large initial sample size, however a small portion of patients assessed were actually included. The fact that 75% did not consent raises internal validity concerns.

- There was a low incidence of side-effects following the administration of both these medications during the study.

- While this may not be directly applicable to emergency department patients unless boarding occurs for a significant amount of time, this may affect how hypoactive delirium is managed in new and upcoming ED-ICUs as the care time of these patients is typically longer than an average ED length of stay.

- Although no alternatives were stated, less may be more in this case, and not administering any medication may be preferred.

- For hyperactive delirium, antipsychotic use may have an important role. However there appears limited to no utility for their use in hypoactive delirious patients, the predominant form of delirium.

- Treatment for hypoactive delirium remains non-pharmacologic. Efforts should be made at recognizing and understanding underlying causes for the patient’s delirium. Interventions should include providing reorientation, improving sleep wake times, encouraging early mobility, and addressing any remaining barriers to sensory perception (ie. Obtaining home glasses, hearing aids, etc).

Potential to Impact Current Practice:

- From 2001 to 2009 the length of stay for critically ill patients in the emergency departments increased from 185-245 minutes.19Subsequently, prolonged boarding times have been associated with worse patient outcomes.20It is important to screen for hypoactive delirium and distinguish it from hyperactive delirium using scores like CAM-ICU. The recognition of hypoactive delirium and avoidance of traditionally administered antipsychotics may be the first steps in benefiting these patients.

Clinical Bottom Line:

- It is vital that the underlying cause and type of delirium be differentiated early as there is limited, if any, use for antipsychotics in patients with hypoactive delirium when compared to placebo. On the other hand, the use of antipsychotics may play a vital role in hyperactive delirium.

Guest Post By:

Mark Ramzy DO, EMT-P

Mark Ramzy DO, EMT-P

Drexel University

Philadelphia, PA

Twitter: @MRamzyDO

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- Josh Farkas at PulmCrit (EMCrit): No More Antipsychotics for Delirium? Not So Fast!

- Fraser Magee at The Bottom Line: MIND-ICU

REFERENCES:

- Girard T, et al. Haloperidol and Ziprasidone for Treatment of Delirium in Critical Illness. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018. PMID: 30346242

- Devlin JW, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2018. PMID: 30113379

- Girard TD, et al. Clinical phenotypes of delirium during critical illness and severity of subsequent long-term cognitive impairment: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2018. PMID: 29508705

- Ely EW, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA 2004. PMID: 15082703

- Girard TD, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2010. PMID: 20095068

- Shehabi Y, et al. Delirium duration and mortality in lightly sedated, mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care Med 2010. PMID: 20838332

- Ouimet S, et al. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007. PMID: 17102966

- Lin SM, et al. The impact of delirium on the survival of mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004. PMID: 15640638

- Ely EW, et al. Current opinions regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med 2004. PMID: 14707567

- Morandi A, et al. Worldwide survey of the “Assessing pain, Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, Choice of drugs, Delirium monitoring/management, Early exercise/mobility, and Family empowerment” (ABCDEF) bundle. Crit Care Med 2017 PMID: 28787293

- Devlin JW. Et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 2018. PMID: 30113379

- Page VJ, et al. Effect of intravenous haloperidol on the duration of delirium and coma in critically ill patients (Hope-ICU): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2013 PMID: 24461612

- Devlin JW, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med 2010. PMID: 19915454

- Inouye SK, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. Ann Intern Med.1990 PMID: 2240918

- F. Jorm, et al. The Informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol Med (1989). PMID: 2594878

- Shehabi Y, et al. Sedation intensity in the first 48 hours of mechanical ventilation and 180-day mortality: a multinational prospective longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med 2018. PMID: 29498938

- Hosker C. et al. Hypoactive Delirium. The British Medical Journal. 2017. PMID: 28546253

- Farkas, J. PulmCrit: No more antipsychotics for delirium? Not so fast!. Nov. 2018 http://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/antipsychotics-delirium/

- Herring AA, et al. Increasing critical care admissions from U.S. emergency departments, 2001–2009. Crit Care Med. 2013. PMID: 23591207

- Mathews K, et al. Effect of Emergency Department and ICU Occupancy on Admission Decisions and Outcomes for Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care Med. 2018 PMID: 29384780

Post Peer Reviewed By: Frank Lodeserto, MD (Twitter: @FrankLodeserto), Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami), and Salim Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Delirium in Critical Illness: Haloperidol vs Ziprasidone? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.