Background Information:

Background Information:

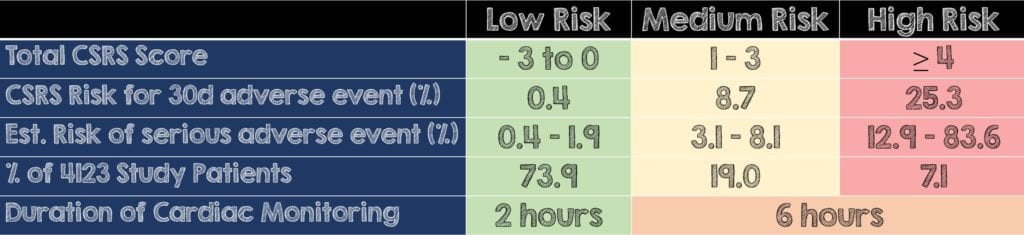

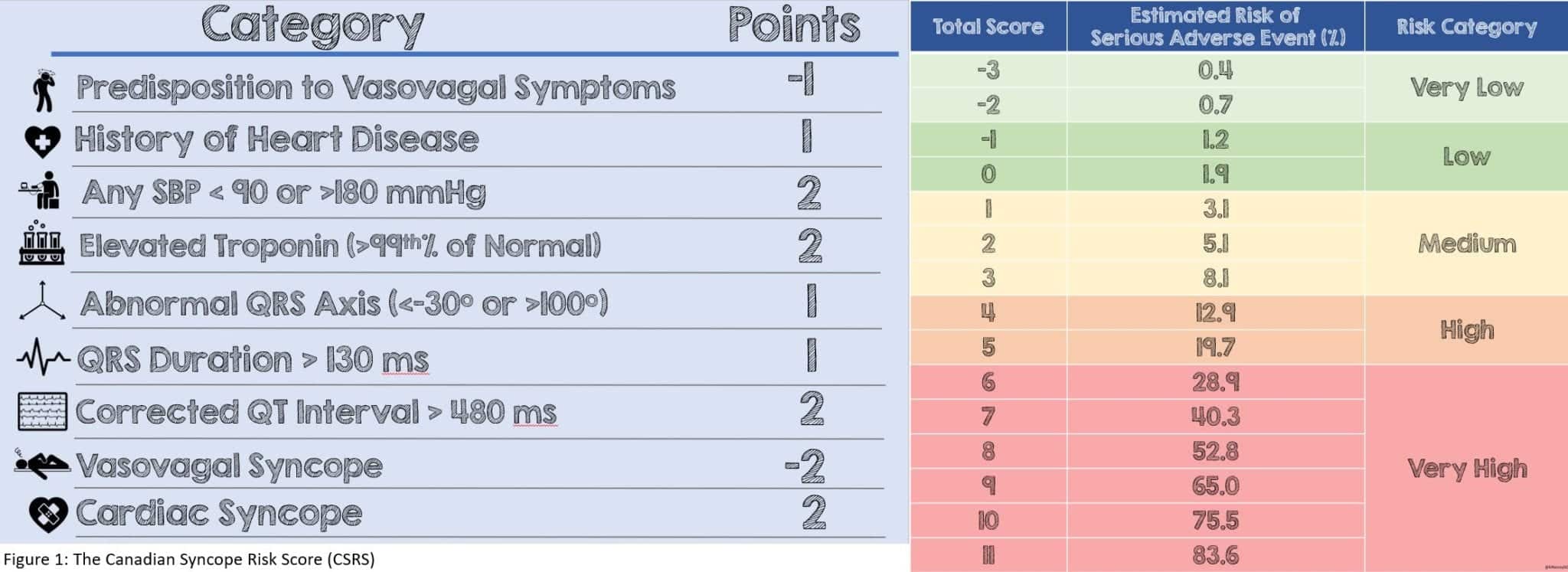

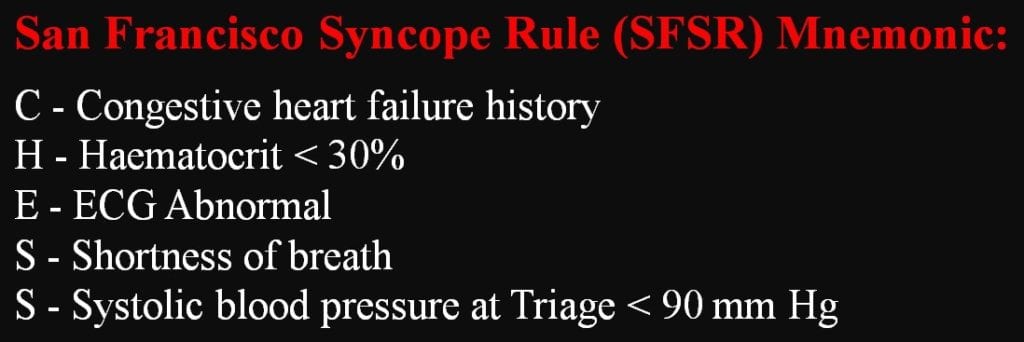

Syncope is defined as a sudden transient loss of consciousness (LOC) followed by complete resolution. It represents 1-3% of all emergency department (ED) visits. 1 1% of all hospitalizations are due to syncope as it may have resulted from a serious underlying condition, such as arrhythmia, acute cardiac ischemia, pulmonary embolism or internal hemorrhage. 2,3 Prior studies have demonstrated that up to a half of these serious conditions, particularly arrhythmias, are missed during ED evaluation and become evident after disposition. 1 Several risk stratification tools, such as the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS; Figure 1) and the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR; Figure 2) have been developed to help identify serious outcomes. 4,5 The authors of this study sought to describe the time to occurrence of serious arrhythmias relative to when the patient arrived in the ED and based on their CSRS risk category. Furthermore, their goal was to use the results of this study to provide guidance for decision making regarding duration and location of cardiac monitoring.

Clinical Question:

- To describe the incidence and time to arrhythmia occurrence following syncope and to inform decisions regarding duration of monitoring based on ED risk stratification using CSRS

What They Did:

- An observational prospective cohort study of all adult patients across 6 EDs who presented within 24 hours of a syncopal episode

Inclusion Criteria:

- Adult ED patients (over the age of 16)

Exclusion Criteria:

-

- Prolonged LOC (>5 minutes)

- Obvious witnessed seizure

- Mental status changes from baseline

- Head trauma causing LOC

- Major trauma

- Unable to obtain history (ie. Language barrier, intoxication with drugs or alcohol)

Outcomes:

- Primary Outcome:

-

- Time occurrence of serious arrhythmia relative to ED arrival time based on CSRS risk category

- The detection or occurrence of Serious Outcome within 30 days of syncope

- Serious Outcome was defined as: Death, arrhythmia, MI, serious structural heart disease, aortic dissection, PE, severe pulmonary HTN, significant hemorrhage, SAH, and other serious condition causing syncope, or procedural interventions for treatment of syncope

-

Secondary Outcome:

- Optimal duration of cardiac monitoring and location of such monitoring

Results:

Patient enrollment:

- 5581 patients were analyzed of the total 5719 enrolled with the mean age being 53.4 years

- 6% hospitalization rate, one that is much lower compared to the United States’ 32% of ED admissions6

- Timing: Median time to ED after syncopal episode was 1.1 hours

-

Risk Stratification

- 4123 (or 73.9% of total patients) = Low Risk

- 1062 (or 19%) = Medium Risk

- 396 (7.1%) = High Risk

- Low Risk -> 15 had the following arrhythmic outcomes described below, and of them, 6 within 2 hours of ED arrival.

-

-

- 6 had sinus node dysfunction

- 4 patients with new or uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

- 2 patients with supraventricular tachycardia

- The remaining 3 out of the 15 had high risk issues characterized by 2 having a high degree atrioventricular (AV) block and one requiring pacemaker placement

-

- Medium Risk -> 92 had arrhythmic outcomes, 45 within 6 hours of ED arrival

- High Risk -> 100 had arrhythmic outcomes, 47 within 6 hours of ED arrival

- Based on the 30-day follow-up data:

-

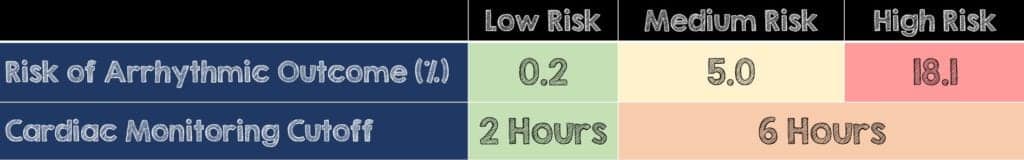

- 0.2% of the low risk patients experienced an arrhythmic outcome after the cardiac monitoring cutoff point of 2 hours. In the medium and high-risk groups, that proportion of patients was 5.0% and 18.1%, respectively.

Critical Results:

Serious outcomes:

- Only 12 (or 0.2%) patients suffered death from an unknown cause.

- It is important to know that of the 30 patients (or 0.6%) who had an arrhythmia only 14 of them (0.3% of enrolled patients) would have benefited from an immediate intervention:

-

-

- 5 High-grade AV block

- 4 ventricular arrhythmias

- 4 requiring pacemaker/AICD insertion

-

- 505 of the arrhythmic outcomes were identified within 2 hours of ED arrival in low risk patients and within 6 hours in medium and high-risk patients

- Of all the 417 serious outcomes (or 7.5% of enrolled patients) 161 were arrhythmias which consisted of:

-

-

- 61 were sinus node dysfunction

- 43 had new or uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

- 30 High-grade AV blocks

- 19 Ventricular arrhythmias

- 8 Supraventricular Tachycardias

-

- There was a subgroup of 30 patients who had a pacemaker/implantable cardio-verter-defibrillator placed within 30 days. Since the authors confirmed device insertion over telephone follow-up they listed several reasons as to not being able to identify the arrhythmia:

-

-

- No medical records available for review

- Arrhythmia was not documented or captured on a rhythm strip

- Device was inserted at the discretion of the treating electrophysiologist

-

- Of the 161 patients with arrhythmias, 63 had pacemakers inserted, 8 had internal cardiac defibrillators implanted, 5 underwent cardioversion, 3 had ablations performed and the remainder were managed medically.

- Overall, 91.7% of arrhythmic outcomes among medium and high-risk patients were identified within 15 days.

- ZERO low risk patients experienced ventricular arrhythmias or unexplained death whereas 0.9% of medium risk patients and 6.3% of high-risk patients experienced them

Strengths:

- Multicenter study over 6 different EDs where patients were consecutively enrolled and not a convenience sample

- Emergency department-based study on a common ED chief complaint

- List of serious outcomes and list of prespecified serious arrhythmias was selected by an “international panel of experts” as conditions that needed to be identified during the patients ED visit or identified in the short term

- Utilized an already developed clinical decision tool to risk stratify syncope patients that expands beyond CHESS (CHF, Hematocrit, Electrocardiogram, Shortness of breath, Systolic blood pressure).

- Collected data on various phases of the patient’s care (ie. Pre-hospital, inpatient and discharge)

- Four-step structured review of all available medical records:

-

- Reviewed not just this ED visit but ones after, hospitalizations & outpatient visits

- Scripted telephone interview 30-days following

- Looked at all local hospitals within the province of Ontario and Alberta using a national database

- For patients unable to be reached by phone they looked at provincial coroner’s office (as all sudden and unexpected deaths have to be reported)

- 2-Blinded physicians reviewed all the serious outcomes and disagreements were dealt with by a third physician if needed

- Only 6% of the total enrolled were lost to follow up

Limitations:

- Since this study was embedded within a larger study and performed as a secondary analysis, there was no a priori sample size calculated before hand.

- When a troponin was not obtained it was counted as normal. This may be a bit pre-emptive, just because a lab value was not obtained does not mean it’s normal.

- In over 1500 patients, or a quarter of those analyzed, time of syncope was not recorded

- 20% of eligible patients were not enrolled and uncertain cases were coded as missed

- 261 patients who were younger with low prevalence of comorbidities, didn’t have an ECG performed because the treating emergency physician at the time thought they were low risk

- All hospitals were Canadian and their ability to easily obtain medical records using a more unified health system makes this a confounding factor to external validity

- Decision to perform outpatient cardiac monitoring was left up to treating EM physician

- The authors do not define exactly what they mean by a “short term hospitalization” when talking about admitting those high-risk patients.

- All the study centers were urban locations and the authors recognize that longer prehospital times may resulted in missed transient arrhythmias.

- Furthermore, since transport times were short and unaccounted for, this may further decrease this study’s reproducibility in the community settings.

Discussion:

- The authors report the prevalence of their findings as in line with a 1.6% overall 30-day mortality reported in a meta-analysis and the 30-day rate of ventricular arrhythmias found in the validation phase of the San Francisco Syncope Rule.4, 7

- Among patients with moderate- and high-risk CSRS scores, the vast majority of the arrhythmic serious conditions occurred within 15 days of the index syncope

- The authors state that as long there is no suspected evolving non-arrhythmic serious condition (ie. Sepsis), and after appropriate work-up, medium risk patients can be discharged after 6 hours with consideration for an outpatient cardiac monitoring device. This is too much of a broad and generalized statement and instead should emphasize the importance incorporating the overall patient’s clinical picture in their disposition.

- In regard to an outpatient cardiac monitoring device, this is not something routinely done upon discharge from most ED in the United States, especially in large urban academic centers. This may play into a benefit of a more unified Canadian health care system may better facilitate outpatient follow-up.

- It is important to note that this study applies to a very narrow subset of patients with serious outcomes. While the other causes of syncope are equally important and should not be missed, they were not the focus of this study.

- Always remember that no matter the risk score used (CSRS, SFSR, etc), the management and disposition of each patient should be tailored to their particular clinical picture. Clinical decision tools should not supersede one’s physical exam skills and clinical gestalt.

Author’s Conclusions:

- The authors found that 2 hours for low-risk patients and 6 hours for medium- and high-risk patients were the optimal cut points for ED monitoring. The authors add that a 15-day outpatient monitoring for medium and high risk patients should be considered. They lastly state that high-risk patients may benefit from a short hospitalization.

Our Conclusion:

- When using the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to identify low risk patients, without obvious serious condition, consider discharging them with outpatient follow up after 2 hours of observation in the ED. While medium risk patients can likely be discharged following 6 hours of cardiac monitoring, there should be a low-threshold for admission based on their overall clinical picture. High risk patients may benefit from a hospital admission for further evaluation, establishment of follow-up after discharge, and a needs assessment for outpatient cardiac monitoring.

Potential to Impact Current Practice:

- Only 0.6% of all medium or high-risk patients on the CSRS score had ventricular arrhythmias and died of an unknown cause. All ventricular arrhythmias were identified within 15 days of index syncope presentation. The decision to discharge a patient with outpatient cardiac monitoring depends on several factors which includes but is not limited to: Access and/or ability to follow-up outpatient, physician-patient preference, local practice environment and medicolegal considerations

Clinical Bottom Line:

- Cardiac monitoring cutoff periods based on patient risk for adverse outcomes are not only clinically sensible but also serve to balance over-testing vs benefit of diagnostic yield. While the risk factors, times and recommended dispositions based off this study are derived below, it is important to recognize that various clinicians in different healthcare systems may have dissimilar thresholds

- Low Risk (2-hour observation) = Residual 0.2% risk of serious arrhythmic outcome (ZERO of the low risk cohort were ventricular arrhythmias or death) and can be discharged home

- Medium Risk (6-hour observation) = Residual 5.0% risk of serious arrhythmic outcome (0.9% of the medium risk cohort were ventricular arrhythmias or death) and can most likely be discharged home but requires follow-up within 24-48hours

- High Risk (6-hour observation) = Residual 18.1% risk of serious arrhythmic outcome (6.3% of the high risk cohort were ventricular arrhythmias or death) and likely need to be admitted if follow-up cannot be arranged before 24-48 hours

For more on this topic, check out these other FOAMed Resources:

- REBEL EM’s Anand Swaminathan: Predicting Arrhythmias After Syncope

- More from Swami: 30 Day Outcomes in Syncope vs Near Syncope

- Ryan Radecki at EM Lit of Note: Predicting Poor Outcomes After Syncope

REFERENCES:

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Duration of Electrocardiographic Monitoring of Emergency Department Patients With Syncope. Circulation. 2019; PMID: 30661373

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Emergency department management of syncope: need for standardization and improved risk stratification. Intern Emerg Med. 2015; PMID: 25918108

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Outcomes in Canadian emergency department syncope patients: are we doing a good job? J Emerg Med. 2013 PMID: 23218198

- Quinn J, et al. Prospective validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; PMID: 16631985

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016; PMID: 27378464

- Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA., Jr Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to US Emergency departments, 1992–2000. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 PMID: 15466144

- Solbiati M, et al. Syncope recurrence and mortality: a systematic review. Europace. 2015; PMID: 25476868

Figure 2: San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR). Image from Medicalchemy Acute Medicine

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Duration of Electrocardiographic Monitoring of Emergency Department Patients with Syncope appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.