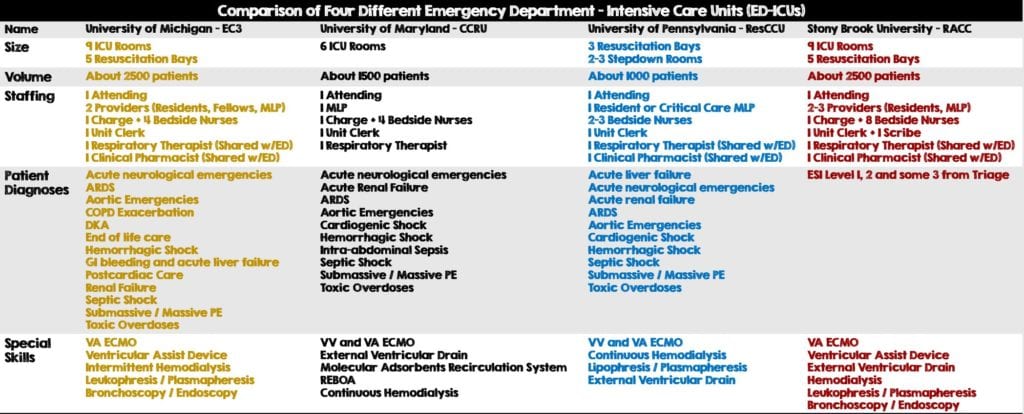

Background Information: Critical care and emergency medicine are frequently intertwined as the resuscitation of critically ill patients occurs in both environments. While the majority of these patients come through the emergency department (ED), the resuscitation of critically ill patients is not defined by a geographic location, but rather a set of principles designed to deliver appropriate care in a timely fashion.1,2 Increased numbers of critically ill patients in combination with decreased availability of intensive care unit (ICU) beds and a shortage of intensivists has led to a shift in critical care being delivered in the ED.3 Furthermore the lack of ICU beds, among many other factors, have contributed to a prolonged length of stay (LOS) of already admitted patients known as “ED Boarding”. Another factor to consider, is that providing prolonged critical care in a traditional ED setting is challenging as it requires more staff and is often associated with increased mortality. Multiple studies have demonstrated an association of worsened outcomes when patient’s ED LOS is greater than 6 hours and, in the United States, 33% of all ICU admissions from the ED have an ED LOS greater than 6 hours.1,4 A proposed solution has been the development of ICUs housed within the ED known as ED-ICUs. While only a handful exist, this new method of care delivery aims to reduce the time it takes for patients to receive critical care and offset the strain on current ICUs (Table 1)4. The authors of this study sought to determine the association of ED-ICUs on 30-day mortality and inpatient ICU admission.

Background Information: Critical care and emergency medicine are frequently intertwined as the resuscitation of critically ill patients occurs in both environments. While the majority of these patients come through the emergency department (ED), the resuscitation of critically ill patients is not defined by a geographic location, but rather a set of principles designed to deliver appropriate care in a timely fashion.1,2 Increased numbers of critically ill patients in combination with decreased availability of intensive care unit (ICU) beds and a shortage of intensivists has led to a shift in critical care being delivered in the ED.3 Furthermore the lack of ICU beds, among many other factors, have contributed to a prolonged length of stay (LOS) of already admitted patients known as “ED Boarding”. Another factor to consider, is that providing prolonged critical care in a traditional ED setting is challenging as it requires more staff and is often associated with increased mortality. Multiple studies have demonstrated an association of worsened outcomes when patient’s ED LOS is greater than 6 hours and, in the United States, 33% of all ICU admissions from the ED have an ED LOS greater than 6 hours.1,4 A proposed solution has been the development of ICUs housed within the ED known as ED-ICUs. While only a handful exist, this new method of care delivery aims to reduce the time it takes for patients to receive critical care and offset the strain on current ICUs (Table 1)4. The authors of this study sought to determine the association of ED-ICUs on 30-day mortality and inpatient ICU admission.

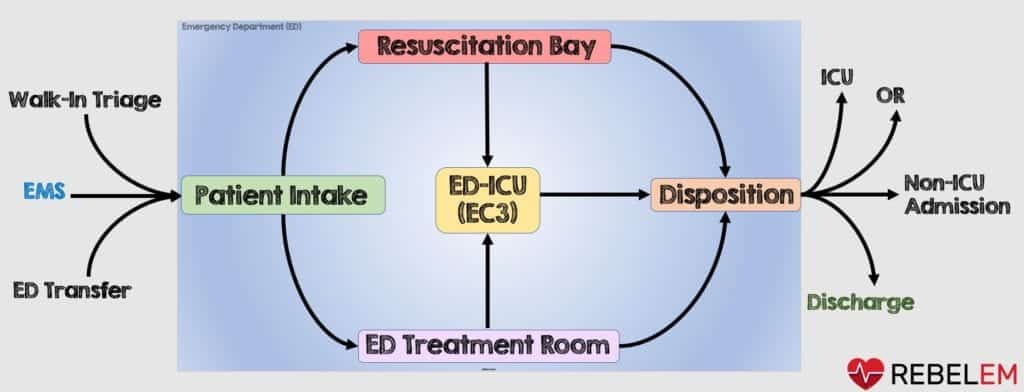

Figure 1: Patient flow diagram of how the EC3 ED-ICU was incorporated into ED operations

Table 1: Comparison of Four Different Emergency Department – Intensive Care Units (ED-ICUs) throughout the United States

Clinical Question:

- How does an emergency department-based ICU care delivery model affect mortality among ED patients and impact inpatient ICU admissions?

What They Did:

- Retrospective cohort analysis through chart review of patient outcomes and use of resources. Data was collected at a single large urban center before and after the implementation of an ED-based ICU and split into two groups:

- Pre-EC3 Cohort: Defined as all ED visits from September 2nd, 2012 to February 15th 2015

- Post-EC3 Cohort: Defined as all visits to the ED from February 16th, 2015 to July 31st 2017.

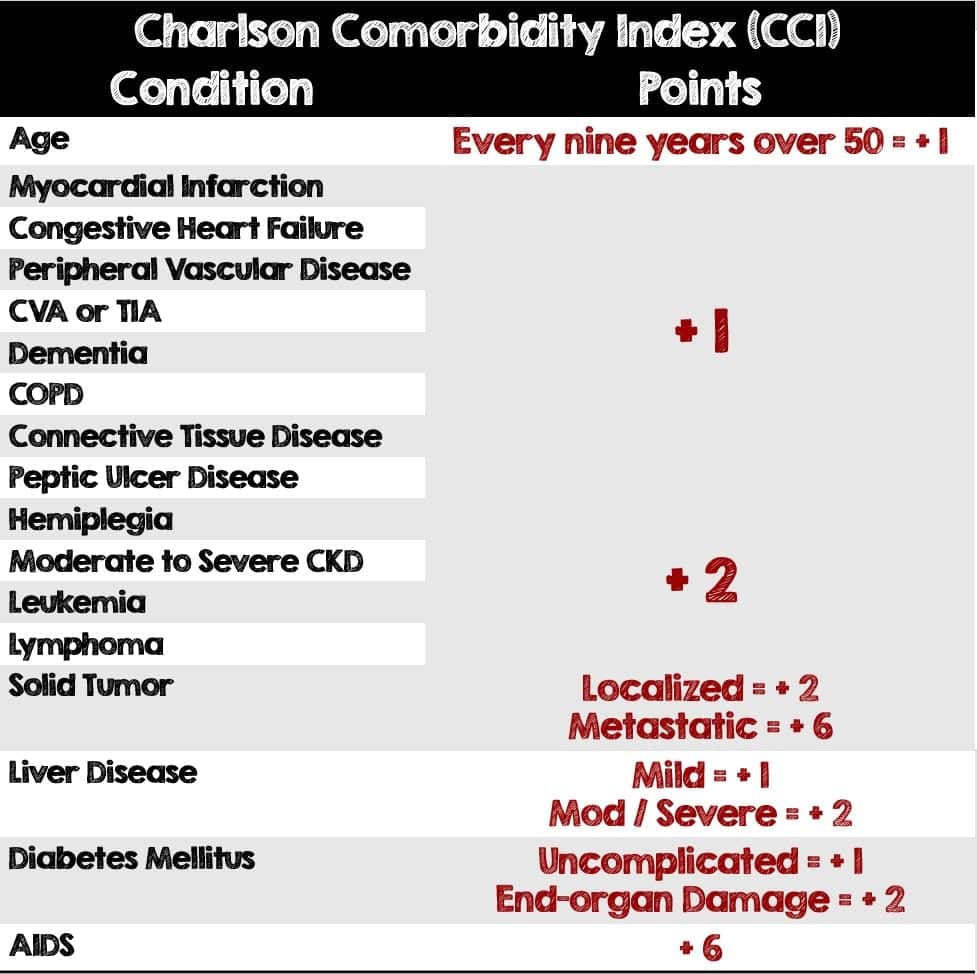

- Investigators used multiple logistic regression analyses. Among them, a weighted index of seventeen conditions called, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). This was initially used to predict 1-year survival and then later modified to predict 10-year survival (Table 2). Another analysis used was the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a triage system that classifies patients into a 1 – 5 category on the basis of acuity and resources.

Table 2: Components and point breakdown of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)

Inclusion Criteria:

- Any patient coming through the ED over the age of 18 years

Exclusion Criteria:

- The authors do not explicitly state any exclusion criteria

Outcomes:

- Primary: 30-day mortality outcome and ICU admission rate among all ED patients before and after ED-ICU implementation

-

Secondary:

- 30-day mortality after hospital admission

- In-hospital mortality

- 24-hour mortality

- Mortality prior to hospital admission

- Short-stay ICU admissions (defined by the authors as less than 24 hours)

- Transfer to ICU within 24 hours of ED-admission to non-ICU bed

- Mortality was determined based on death rate or confirmed to be alive in the electronic health record.

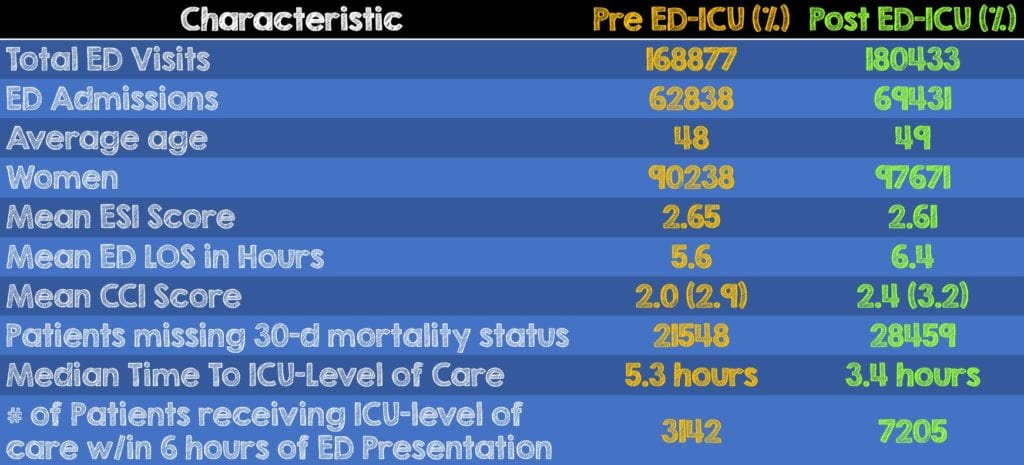

Results:

- A total of 349,310 patients were enrolled and split between the two groups:

- The Pre ED-ICU group had 168,877 patients

- The Post ED-ICU group had 180,433 patients

- There was an increase in patient acuity as denoted by the lower ESI score and the longer ED LOS in the Post-EC3 group when compared to the Pre-EC3 group.

- A 20% increase in the CCI Score is noted in the Post EC3 group when compared with the Pre-EC3 Cohort and is reflective of increases in age and comorbidity over time.

- The median time to ICU-level of care decreased 1.9 hours and number of patients receiving that ICU-level of care nearly doubled in the post-EC3 group compared to the Pre-EC3, indicating more patients were receiving higher level of care much faster.

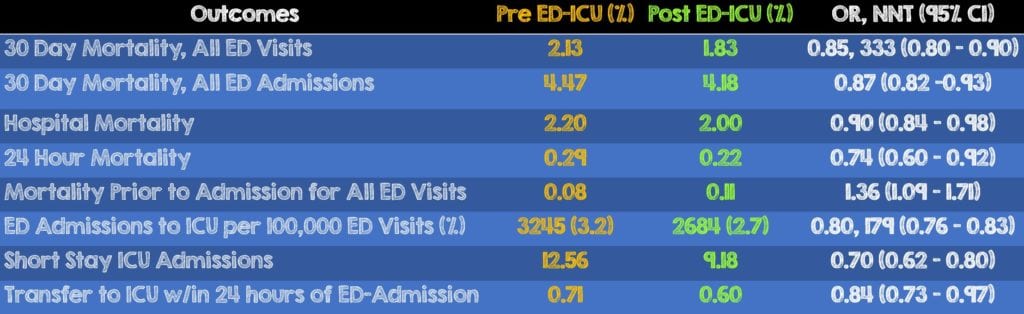

Critical Results:

- There was a decrease in 30-day mortality, Hospital Mortality, 24-hour mortality, ED admissions to the ICU, Short Stay ICU admissions and transfers to the ICU within 24 hours of ED-Admission in the Post-EC3 cohort when compared to the Pre-EC3 group

- Restricting analysis only to patients with an ESI of 1 or 2 was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the odds of 30 day mortality (adjusted OR, 0.87, 95% CI, 0.82-0.92)

- There was an increase in mortality prior to admission for all ED visits in the Post-EC3 group and it is unclear what they may have been due to (ie. Initiation of comfort care, complications from procedures, etc)

Strengths:

- First study looking at how this ED-ICU model of care delivery impacts patient outcomes

- Consecutive sampling analyzing all visits from the entire ED population to prevent patient selection bias and ensure a heterogenous population of underlying disease processes

- Patient safety was considered as the following two endpoints were included in the assessment and neither were found to be increased: Emergent transfers from non-ICU floors to the ICU within 24 hours of admission from the ED and risk-adjusted 24 hour mortality of ED patients.

- The authors including how the ED-ICU affects the actual ICU as part of their primary outcome was extremely helpful as it factors in the impact of this care delivery model from both the inpatient and ED side of things.

- Correlated use of the Charlson Comorbidity Index with the Emergency Severity Index in order to identify a representative range of acuity within the ED patient population

Limitations:

- This study’s overall before and after design serves as a major limitation as it is a retrospective chart review. These types of studies are unable to control for exposure or outcome assessment and rely on accurate record keeping.

- The statistically significant differences observed in this study could be attributable to a large sample size which is often required by retrospective chart review studies looking at rare outcomes.

- Furthermore, this study took place at a single center, urban academic center thus potentially limiting its generalizability in settings differing from this one.

- There was no acceptable standard for risk adjusting patients who are critically ill in the ED Setting. The authors acknowledge this as a major limitation since the same traditional scoring systems that have been validated for in the ICU are poor predictors of mortality when applied in the ED.

- A new electronic health record (EHR) rollout in the middle of the study may have affected risk-adjusted mortality for the Pre ED-ICU group

- The authors assumed that patients with unknown mortality status were alive 30 days after their ED visit and thus may have skewed the analysis by overestimating the mortality benefit. They performed the analysis again with those patients excluded, the differences remained statistically significant and similar in magnitude

- The authors acknowledge that increasing the number of clinicians providing care in the department as a whole after the ED-ICU opened may have contributed to improved survival

- Over the period of the study, advancements in disease treatments may have contributed to outcome differences among both of the groups

- For the administrative side of hospital management, there was no mention of the cost impact this had on either the emergency department or the hospital as a whole.

- Lastly, the authors did not have any further elaboration of patient outcomes beyond mortality (ie. CPC or modified Rankin Score).

Discussion:

- The variables potentially associated with improved mortality as seen in this study are multifactorial and will require more in-depth analysis.

- Nurse staffing and the patient to nursing ratio in the ICU and these ED-ICUs is 2:1 compared to the 4:1 or sometimes 6:1 it is in the ED. While the issue was neither studied nor discussed, an increase in ED nursing staff may also improve patient outcomes at a significantly lesser cost.

- Mortality is an important patient-oriented outcome, however other note-worthy patient-oriented outcomes affected morbidity (i.e. quality of life) should also be considered and were not included in the results of this publication.

- This study took place over 5 years and there may have been many changes over this time period in the way we manage some of the diseases that got these patients into the ICU in the first place. The authors acknowledge this as a limitation, calling them “secular factors”. However, they do not include any information about any outpatient follow-up (or the lack thereof) before or after their ED visit.

- Being the first to look into the impact of this care delivery model, this study helps by increasing awareness and starting the discussion of how patient outcomes can be affected.

- Even with an increase in the mean severity of illness, overall admission rate and patient age during the study, the number of ICU admissions was reduced. It’s important to note, that decreased patient acuity was not one of the factors that reduced ICU admissions.

- A major highlight of this study was the 30% decrease in short-stay ICU admissions. Avoiding these short-stay admissions allows the inpatient ICU to optimize bed allocation to patients decompensating on non-ICU hospital floors or increasing ICU transfers from other hospitals.

Author’s Conclusions:

- “Implementation of a novel ED-based ICU was associated with improved 30-day survival and reduced inpatient ICU admission. Additional research is warranted to further explore the value of this novel care delivery model in various health care systems.”

Our Conclusion:

- ED-ICUs are becoming increasingly more popular as patients are getting sicker and the demand for critical care rises. While this study opens the discussion on how this care delivery model impacts patient mortality, there are many more factors impacting patient outcomes that need to be considered. Furthermore, the methodology and overall design of this study served as a major limiting factor. In the future as more ED-ICUs are developed, we should be comparing them with actual ICUs or different staffing models in the ED to truly see if where we deliver critical care has any effect on patient outcomes.

Clinical Bottom Line:

- This study, despite its design and limitations, helps raise awareness of ED-ICUs as a whole and they may be one of many components affecting patient mortality. Additional studies comparing ED-ICUs to actual ICUs vs improved staffing models in the ED are needed to further assess the impact on patient outcomes.

For More on This Topic Checkout:

REFERENCES:

- Herring AA, et al. Increasing critical care admissions from US emergency departments, 2001-2009. Crit Care Med. 2013; PMID: 23591207

- Leibner E, Hsu C, Wright B, Bassin B. Anatomy of resuscitative care unit: expanding the borders of traditional intensive care units. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2019. PMID: 30940715

- Gunnerson, K., et al. Association of an Emergency Department–Based Intensive Care Unit With Survival and Inpatient Intensive Care Unit Admissions. JAMA Network Open 2019; PMID: 31339545

- Chalfin DB, et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007; PMID 17440421

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Impact of ED-ICUs on Mortality and ICU Admissions appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.