Background Information:

Obtaining definitive control of the airway, when indicated, is the responsibility of the emergency medicine physician. Traditionally patients were managed on the ventilator with lung volumes of 10 – 15 ml/kg. However, that practice is long-outdated and patients managed on lower tidal volumes (6 ml/kg) were found to have decreased mortality.1 This practice of lower tidal volumes has been termed “lung protective ventilation” (LPV) and is now the standard of care for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Ventilator-associated lung injury and inflammation can occur even during short-term mismanagement can worsen patient outcomes.2 Finally the settings initiated early in a patient’s care are often carried forward unchanged into their hospital and ICU stay. Over the past few years, there has been an increase in emergency department (ED) volumes and lengths of stay. The result of this ED capacity strain and less than ideal patient to staff ratios has led to delays in interventions, treatments and care adjustments. Thus it is imperative that the emergency physician be familiar with post-intubation ventilator management include the use of LPV. The authors of this retrospective observational study sought to investigate what system factors, if any, serve as obstacles to the implementation of standard-of-care LPV on critically ill ED patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), particularly those at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Obtaining definitive control of the airway, when indicated, is the responsibility of the emergency medicine physician. Traditionally patients were managed on the ventilator with lung volumes of 10 – 15 ml/kg. However, that practice is long-outdated and patients managed on lower tidal volumes (6 ml/kg) were found to have decreased mortality.1 This practice of lower tidal volumes has been termed “lung protective ventilation” (LPV) and is now the standard of care for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Ventilator-associated lung injury and inflammation can occur even during short-term mismanagement can worsen patient outcomes.2 Finally the settings initiated early in a patient’s care are often carried forward unchanged into their hospital and ICU stay. Over the past few years, there has been an increase in emergency department (ED) volumes and lengths of stay. The result of this ED capacity strain and less than ideal patient to staff ratios has led to delays in interventions, treatments and care adjustments. Thus it is imperative that the emergency physician be familiar with post-intubation ventilator management include the use of LPV. The authors of this retrospective observational study sought to investigate what system factors, if any, serve as obstacles to the implementation of standard-of-care LPV on critically ill ED patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), particularly those at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Paper: Owyang CG, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on lung-protective ventilation utilization for critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2019 Aug; PMID: 30954692

Clinical Question:

What is the impact of system factors in the implementation of standard-of-care LPV in critically ill ED patients admitted to the ICU?

What They Did:

- Retrospective, observational cohort study in a single high-volume academic hospital

- The ED had a 5 bed area used for ongoing management and resuscitation of patients who clinically deteriorate while boarding or while actively undergo a workup in other sections of the ED. Patients admitted to the ICU and/or patients requiring mechanical ventilation are cohort to these 5 beds.

- The 5-bed area of critically ill patients is staffed by an ED attending and upper level ED resident who simultaneously care for patients in other sections of the ED. The typical nursing to patient ratio is 1:3 with a shared respiratory therapist for the entire ED.

- The default ventilator order set is pre-filled for a tidal volume of 500mL. This could be overwritten with alternative settings by the ordering ED provider

- Crowding metrics obtained at 5-minute intervals and averaged over the ED stay.

- Patients were stratified by acuity using the Mortality Probability Model III.

- This model uses 16 variables to predict ICU mortality by using specific variables to determine a patient’s acuity within 1 hour of admission to the ICU.3 Among these variables are: tachycardia, SBP <90 and time to intubation after arrival.

- Patients at risk for ARDS were stratified by the Lung Injury Prevention Score (LIPS) which predicts the probability of developing ARDS and subsequent mortality.4

- Using factors such as shock, pneumonia, and sepsis this score allows an accurate prediction of developing ARDS.

- Reason for intubation, severity of illness, ARDS risk score, and ventilator settings were extracted from the electronic medical record (EMR).

Inclusion Criteria:

- Adult emergency department patients 18 years or older

- Intubated by EMS in the field or ED providers

- Requiring continuous mechanical ventilation

Exclusion Criteria:

- Intubated in the inpatient service

- Intubated for a procedure or in the operating room

- Patients on chronic mechanical ventilation

- Expired prior to ICU admission

- Those not on volume control mode of ventilation

Outcomes:

Primary

- Final ED mechanical ventilator tidal volume settings of LPV (<8 cc/kg) or non-LPV (>8 cc/kg)

Results:

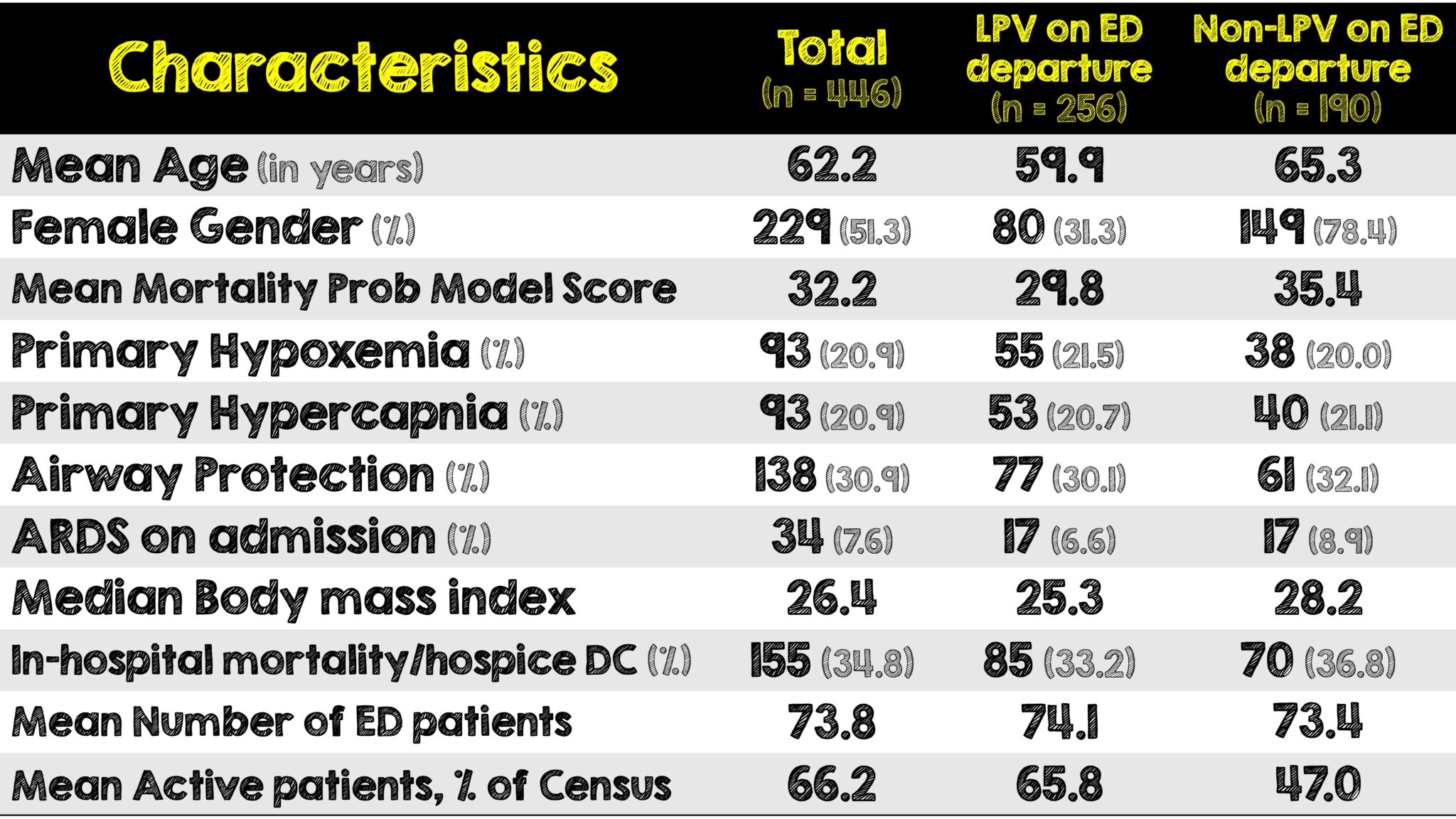

- Controlling for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), increased active ED patients and higher acuity were associated with lower LPV utilizations.

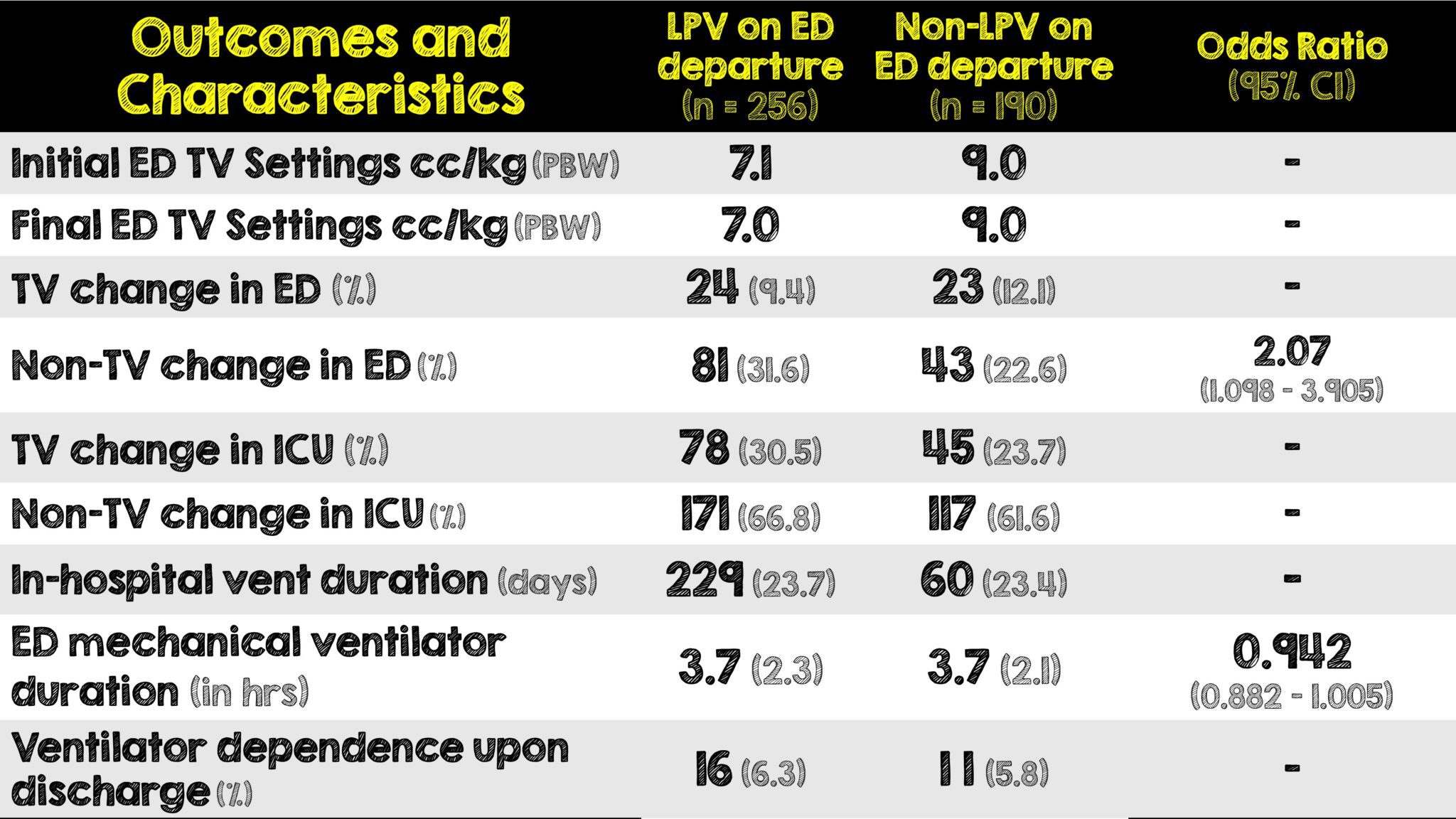

- Ventilator adjustments to non-TV settings were associated with improved odds of LPV adherence.

Critical Results:

- On average, initial TV settings were too high.

- 66% of patients were initiated on the default setting for the ventilator and settings not adjusted. In fact, any TV change in the ED was very minimal.

- The likelihood of departing the ED on LPV settings was not affected by severity of illness nor the risk of ARDS

- 30.5% of patients left the ED on TV settings of 450 mL and 36.1% of patients left the ED on TV settings of 500 mL

Strengths:

- Total ED census data obtained at 5-minute intervals allowed for calculation of how ED crowding affected LPV usage. Prior studies have used annual census or shift level crowding. Thus allowed for evaluation on how the physicians workload affects their usage of LPV.

- First ED-based study to evaluate how operational effects such as crowding can affect patient care in the form of LPV

- Included ARDS criteria relating to the usage of LPV in the ED allowing evaluation as to whether patients with ARDS were more likely to receive LPV settings.

- Data was automatically captured in the EMR so that accurate information was able to be extracted for the study.

- Consecutive enrollment avoided sampling bias

Limitations:

- Retrospective observational study at a single academic center limits external validity (ie. generalizability)

- Over reliance on electronic data capture may have predisposed to a misclassification bias

- Unclear which provider was responsible for ventilator changes

- Under-recognition of ARDS in the ED

Discussion:

- Patients who are intubated in the ED are less likely to be placed on LPV than in the ICU. This is a critical error that leads to poorer outcomes for patients in need of critical care. According to the paper this problem is made worse not by overall census but by the number of active patients a provider has that will eventually be admitted. The strain of making diagnostic decisions eventually becomes exhausted and LPV is overlooked.

- As volumes increase of patients actively being worked up is paired with those who need eventual admission, there is a higher task burden which creates a significant barrier to adequate critical care delivery.

- More concerning is that a patient with a higher severity of illness or at higher risk for ARDS did not receive more diligent attention even in a dedicated resuscitation area

- An important point to note is that it was unclear which provider made ventilator changes. There may have very well been a policy where only RTs can make changes to a ventilator after an order was placed to ensure accurate documentation. Unfortunately, its not clear whether the documentation came from RTs or ED providers.

- Females and patients with increased BMI are at increased risk of not being placed on LPV. This problem is evident by the fact that patients are not being routinely placed on settings reflecting their ideal body weight. Accurate measurements including height can be quickly obtained in triage. This information could then easily be converted to demonstrate the patient’s ideal body weight and thus enabling the physician to make accurate decisions regarding a patient’s ideal tidal volume post intubation.

- A significant portion of patients were placed on the default ventilator settings without changes to the ventilator. This demonstrates that ventilator settings were rarely adjusted to patient weight. Adjustments to non-tidal volume settings correlates to increased usage of LPV.

Author’s Conclusions:

ED patients remain on suboptimal tidal volume settings with infrequent ventilator adjustments during the ED stay. Hospitals should focus on both systemic factors and bedside physician and/or respiratory therapist interventions to increase LPV utilization in times of ED boarding and crowding for all patients.

Our Conclusion:

It is difficult to generalize this study as it is limited to one hospital and its practice. A large problem with this trial is the default ventilator setting in the order set was a TV of 500mL. An even bigger problem is that RTs and ED providers were not adjusting the ventilator to ideal body weight thus setting up patients to less likely receive LPV, especially if in an ED with a high census. More pertinent and relevant takeaway messages have to do with staffing and operations. Critically ill ED patients should be paired with a 2:1 patient to nurse ratio. Ventilator order sets or bundles should be based on ideal body weight as their default setting. Liberating ventilator adjustments to ED providers in addition to RTs could help improve ventilator management regardless of patient location or strain on the ED.

Clinical Bottom Line:

This single center retrospective study highlights important barriers to placing patients on LPV in the ED which include high census, incorrect default ventilator settings in an order set, insufficient staffing, under-recognition of ARDS, policies restricting which providers can adjust the ventilators and the lack of ventilator protocols, all of which have the potential to improve patient outcomes in a regardless of patient location or strain of the ED.

REFERENCES:

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4; PMID: 10793162

- Harvey CE, et al. Initiation of a lung protective strategy in the emergency department: Does an emergency department-based ICU make a difference? Crit Care Explor. 2022 Feb 8;. PMID: 35156050

- Higgins TL et al. Prospective validation of the intensive care unit admission Mortality Probability Model (MPM0-III). Crit Care Med. May 2009. PMID: 19325480

- Gajic O, et al. Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Feb 15; Epub 2010 Aug 27. PMID: 20802164

- Heimberg DH, et al. Quality Improvement Intervention associated with Improved Lung Protective Ventilation Settings in an Emergency Department. Spartan Med Res J. 2022 Feb 24;7(1):29603. doi: 10.51894/001c.29603. PMID: 35291703

Guest Post By:

Karl Bischoff, MD

PGY-2, Emergency Medicine Resident

RWJBH Community Medical Center, Toms River, NJ

Twitter: @KarlJayB

Mark Ramzy, DO

Emergency Medicine Attending and Critical Care Intensivist

Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

RWJBH Community Medical Center, Toms River, NJ

Twitter: @MRamzyDO

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

EMCRIT: MDCalc for the perfect tape-measure intubation

EMCRIT: The Case of an Ugly Truth

First10EM: Emergency Airway Management Part 5: Post intubation care

Post-Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Impact of Emergency Department Crowding on Lung Protective Ventilation appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.