Background: Standard emergency department management of acute pancreatitis has focused on aggressive hydration, analgesia and investigation for an underlying reversible cause (eg gallstones). Recent evidence has challenged the routine use of aggressive hydration as unnecessary. There are also potential harms to large volume fluid resuscitation including progression of pancreatitis and fluid overload with or without respiratory failure. Though the initial recommendation for aggressive fluid resuscitation was not based on substantial evidence, clinicians have been slow to pivot away from this approach. High-quality evidence demonstrating harms is needed to shift the paradigm.

Background: Standard emergency department management of acute pancreatitis has focused on aggressive hydration, analgesia and investigation for an underlying reversible cause (eg gallstones). Recent evidence has challenged the routine use of aggressive hydration as unnecessary. There are also potential harms to large volume fluid resuscitation including progression of pancreatitis and fluid overload with or without respiratory failure. Though the initial recommendation for aggressive fluid resuscitation was not based on substantial evidence, clinicians have been slow to pivot away from this approach. High-quality evidence demonstrating harms is needed to shift the paradigm.

Article: de-Madaria E et al. Aggressive or Moderate Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis (WATERFALL). NEJM 2022. PMID: 36103415

Clinical Question: Does the use of moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis decrease the rate of progression to moderate/severe pancreatitis in comparison to aggressive fluid resuscitation?

Population: Adult patients > 18 years of age diagnosed with acute pancreatitis based on the Revised Atlanta Classification (requires 2 of 3: typical abdominal pain, serum amylase or lipase level higher than 3 times the upper limit of normal or signs of acute pancreatitis on imaging) that presented within 24 hours of pain onset.

Outcomes:

- Primary: Progression to moderately severe or severe acute pancreatitis (according to the Revised Atlanta Classification).

-

Primary Safety Endpoint: Fluid Overload defined by 2 of the following 3:

- Criterion 1: non-invasive evidence of heart failure (ie echo), radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion, invasive cardiac Cath suggesting heart failure.

- Criterion 2: Dyspnea

- Criterion 3: Heart failure signs: peripheral edema, pulmonary rales, increased JVP or hepatojugular reflex

-

Secondary:

- Organ failure

- Local Complications

- Persistent Organ Failure

- Respiratory Failure

- Hospital LOS

- ICU Admission

- ICU LOS

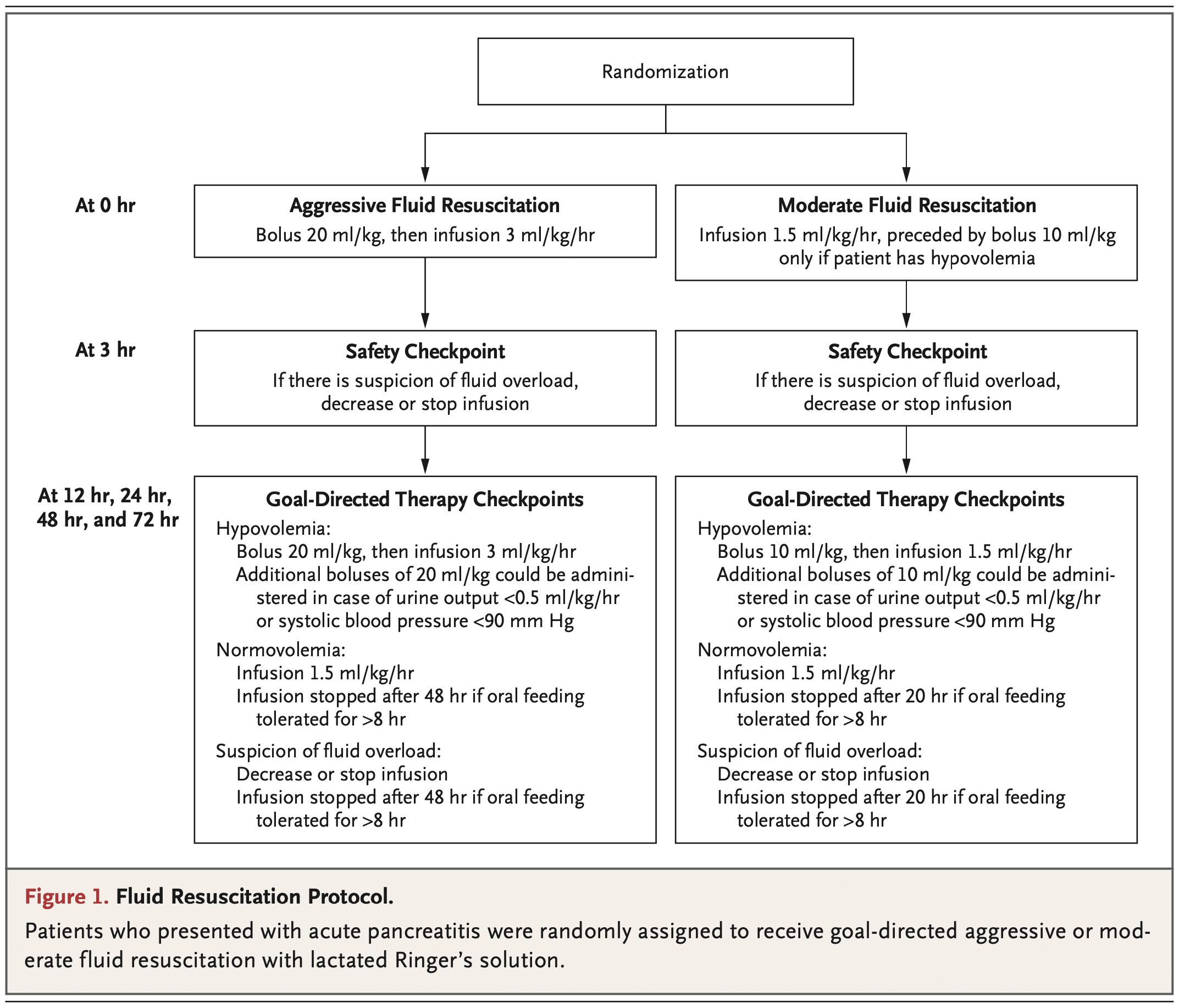

Intervention: LR Bolus of 10 cc/kg in patients with hypovolemia or no bolus in those with normovolemia followed by 1.5 cc/kg/hour of LR

Control: LR Bolus of 20 cc/kg (regardless of fluid status) followed by 3.0 cc/kg/hour of LR

Design: Multicenter, multinational, open-label, parallel-group, randomized, controlled, superiority trial.

Excluded:

- Moderately severe/severe disease on presentation.

- Pre-existing heart failure (NYHA Class II, III or IV)

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Hypernatremia

- Hyponatremia

- Hyperkalemia

- Hypercalcemia

- Life expectancy < 1 year

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Chronic renal failure

- Decompensated cirrhosis

Primary Results

-

- 676 patients were assessed for enrollment with a total of 249 patients meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- No patients were lost to follow up and all patients were analyzed in the group to which they were randomized.

- Median Fluid Received:

- Aggressive: 7.8L (Range 6.5 to 9.8L)

- Moderate: 5.5L (Range 4.0 to 6.8L)

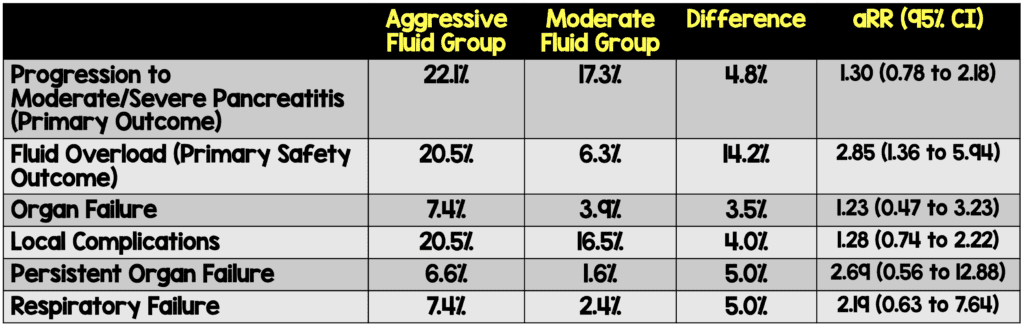

Critical Findings:

The trial was stopped early due to an interim analysis demonstrating a high incidence of fluid overload with no significant difference in the primary outcome.

Strengths:

- Asks a clinically important question with limited prior evidence.

- Patients were consecutively enrolled which minimizes bias.

- Multicenter and multinational which increases external validity.

- Randomization was adequately performed.

- Baseline disease severity was well-balanced between groups.

- Fluid rates and volumes were based on previous RCT based hydration strategies.

- Secondary outcomes were pre-specified which helps in terms of minimizing bias (i.e. cherry picking results).

- Used and intention-to-treat analysis which mimics real world practice compared to a per-protocol analysis.

Limitations:

- Open-label trial which increases risk of bias. This is particularly important as the safety outcome (fluid overload) has some subjectivity built into it.

- Sample size calculation assumed at 35% progression to moderate/severe pancreatitis. The actual rate in the trial was ~ 20%

- Baseline characteristics were not all well balanced. In particular, gallstone pancreatitis was more common in the aggressive fluid resuscitation group.

Discussion:

- The study was stopped early due to an interim analysis demonstrating a significantly higher rate of fluid overload in the aggressive hydration group.

- At the time of trial stoppage, there was a 4.8% non-statistically significant difference in the primary outcome. Though smaller than the preset criteria, a 5% difference (if it persisted) would be clinically significant.

- To find superiority of restrictive fluid administration may require a much larger study as the rate of progression to moderate/severe pancreatitis was overall lower than assumed by the authors and, a 10% difference may be too large for a single intervention to accomplish.

- However, given the statistically significant difference in the primary safety outcome, a larger study shouldn’t be necessary to push clinicians to embrace a restrictive fluid philosophy.

- The aggressive fluid administration arm is far less aggressive than what was historically recommended for pancreatitis. Many of us were trained to administer 4-6 liters of crystalloid to pancreatitis patients as part of initial management.

- Though not statistically significant, many of the secondary outcomes favor moderate fluid administration over aggressive fluid administration regardless of subgroup (ie SIRS vs non-SIRS, volume depletion vs no volume depletion).

Authors Conclusions: “In this randomized trial involving patients with acute pancreatitis, early aggressive fluid resuscitation resulted in a higher incidence of fluid overload without improvement in clinical outcomes.”

Our Conclusions: We agree with the authors. Aggressive fluid administration results in an increased likelihood of fluid overload. Though not statistically significant, the primary outcome as well as many of the important secondary outcomes favor the moderate fluid group as well.

Potential to Impact Current Practice: The tide has been turning against the use of aggressive fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis and this high-quality study should increase the push for a paradigm change. Administer smaller fluid boluses (10 cc/kg) in patients with hypovolemia (and no bolus in those with normovolemia) and start maintenance fluids at 1.5 cc/kg/hour.

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- CorePendium: Pancreatic Disease

- Internet Book of Critical Care: Acute Pancreatitis

- EMCrit: Ep333 – The State of Fluids Show with the EMCrit Core Team

- The Bottom Line: Aggressive or Moderate Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis

References:

- de-Madaria E et al. Aggressive or moderate fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis (WATERFALL). NEJM 2022; 387: 989-1000. PMID: 36103415

- Buxbaum JL et al. Early Aggressive Hydration Hastens Clinical Improvement in Mild acute Pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017. PMID: 28266591

- Ramirez-Maldonado E et al. Immediate Oral Refeeding in Patients with Mild and Moderate Acute Pancreatitis: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial (PADI trial). Ann Surg 2021. PMID: 33196485

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Less is More . . . Again: Speed of IV Fluid Administration in Pancreatitis (WATERFALL Trial) appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.