Background: Critical illness and ICU admission comes with significant consequences – not just from the primary pathology but also from the secondary effects of therapies that may be begun to correct the abnormal physiology. One of these consequences in ventilated patients is the development of stress ulcers in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to bleeding. Over two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU will be prescribed some form of stress ulcer prophylaxis, often in the form of either a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or a histamine-2 receptor blocker (H2RB)1. But which one is better? Are there any risks?

Background: Critical illness and ICU admission comes with significant consequences – not just from the primary pathology but also from the secondary effects of therapies that may be begun to correct the abnormal physiology. One of these consequences in ventilated patients is the development of stress ulcers in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to bleeding. Over two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU will be prescribed some form of stress ulcer prophylaxis, often in the form of either a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or a histamine-2 receptor blocker (H2RB)1. But which one is better? Are there any risks?

The existing evidence of benefit of one over another is limited. Though one systematic review did show a benefit of PPIs, the reviewed data was limited2. Neither drug is without risk either. These include a potential for immunosuppression and increased risk of infections3. More evidence is needed – which is where the Proton Pump Inhibitors vs Histamine-2 Receptor Blockers for Ulcer Prophylaxis Treatment in the Intensive Care Unit (PEPTIC) randomized clinical trial comes in4.

Clinical Question:

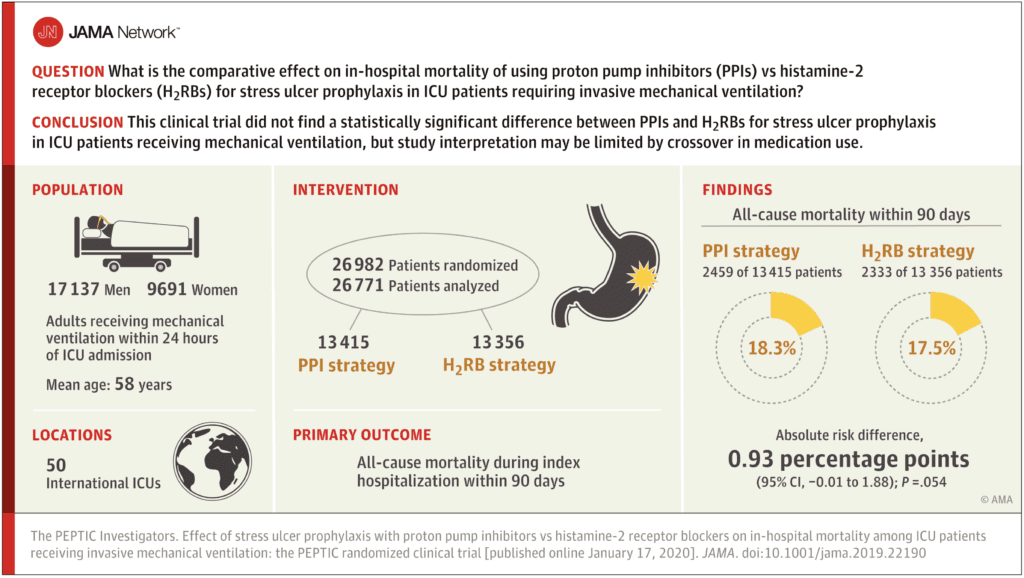

- Does the use of PPIs vs H2RBs for stress-ulcer prophylaxis in mechanically ventilated ICU patients reduce mortality at 90 days?

What They Did:

- This study was designed as a pragmatic, cluster randomized cross-over trial

- An entire unit used one drug for a period of six months, then changed to the other

- The trial was conducted in 50 ICUs in 5 countries (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom) from August 2016 to January 2019

- The intervention arm received PPI as the default prophylaxis agent

- The control arm received H2RBs

- The randomization choice could be over-ridden by the treating physician

- If a patient remained in the ICU during a cross-over period, they continued on their initial therapy

- Because of this, it is important to note that:

- in the PPI group, 82.5% received PPI, 4.1% received H2RB, 1.9% received both, and 11.5% received neither.

- in the H2RB group, 63.6% received H2RB, 20.1% received PPI, 5.1% received both, and 11.2% received neither.

- Thus, 4.1% of PPI group patients got H2RBs and 20.1% of H2RB group patients received PPI

- If the patient developed active gastrointestinal bleeding, they were placed on a PPI per evidence-based guidelines

Outcomes:

-

Primary: 90-day hospital mortality

- This was changed mid-trial (March 2017) – the initial registered primary end point had been a composite of significant gastrointestinal hemorrhage, Clostridium difficile infection, and >10 days on mechanical ventilation. This change was made due to determining mortality was a more preferable outcome measure, and prior to completion of recruitment at any site or review of data.

-

Secondary:

- Clinically important upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- Infection with C. difficile

- ICU and hospital lengths of stay

-

Tertiary:

- Occurrence of ventilator-associated conditions

- Duration of mechanical ventilation

Inclusion:

- Adults 18 years or older

- Critically unwell requiring mechanical ventilation within 24 hours of ICU admission

Exclusion:

- Age less than 18 years

- Prior ICU admission

- Active upper gastrointestinal bleeding as their admission diagnosis

Results:

- Of the 26,982 patients that were randomized, 26,828 were included for the primary analysis.

- PPI group included 13,436 patients

- H2RB group included 13,392 patients

- Mean age was 58 years

- 36.1% were women

- 32.9% were admitted to the ICU following elective surgery

- 30% were admitted to the ICU from the Emergency Department

- 18.4% were admitted to the ICU following emergency surgery

-

- Mean APACHE II scores for both groups were 18.7 (implying in-hospital nonoperative mortality of approximately 25%)

- Median time of exposure to the drug was about 2.7 days for H2RBs and 2.8 days for PPI

- 57 patients had primary outcome data missing

-

Primary Outcome (90-day mortality):

- PPI group – 18.3%

- H2RB group – 17.5%

- RR 1.05 (95% CI 1.00-1.10)

- No significant difference detected

-

Secondary Outcomes

-

Clinically important gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- PPI group – 1.3%

- H2RB group – 1.8%

- RR 0.73 (95% CI 0.57-0.92)

- Lower risk in the PPI group

-

Infection with C. difficile

- PPI group – 0.3%

- H2RB group – 0.43%

- RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.51-1.09)

- No significant difference detected

-

ICU and hospital lengths of stay

- No significant difference detected

-

Tertiary Outcomes

-

Occurrence of ventilator-associated conditions

- PPI group – 6.5%

- H2RB group – 5.8%

- RR 1.18 (95% CI 0.87-1.59)

- No significant difference detected

-

Duration of mechanical ventilation

- PPI group – 48 hours

- H2RB group – 48 hours

- RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.92-1.04)

- No significant difference detected

-

Occurrence of ventilator-associated conditions

-

Clinically important gastrointestinal hemorrhage

Post Hoc Exploratory Analysis

- In a post hoc exploratory analysis, among patients with high illness severity, randomization to PPI was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality compared with randomization to H2RB but barely crossing into statistical significance with 95% CI of RR ranging from 1.05 – 1.25 and 1.00 – 1.11

Strengths:

- This question is relevant to my ICU practice as existing evidence to date on appropriate prophylaxis choice was limited

- The large sample size allowed for an adequately powered trial – in fact this is the largest RCT on this topic

- The recruitment of patients across multiple ICUs in many countries allowed for improved generalizability of the results (though inevitably there will be some debate about the exclusion of US ICUs!)

- The patients included represented a typical, sick ICU population

- Follow up was >95% in this trial, with a worst-best scenario being utilized. Worst case scenario (i.e. in-hospital death within 90 days) and best-case scenario (i.e. survival to hospital discharge within 90 days) was assigned to all patients with missing data for the outcome to ensure statistical significance despite missing data

- Transparency in statistical analysis, with the plan posted online

Limitations:

- Despite a clear protocol, there was non-adherence in some units, with significant crossover occurring in particular in the control (H2RB) arm – 20.1% received a PPI. This puts the overall results into some doubt. Here’s a reminder of the breakdown:

- in the PPI group, 82.5% received PPI, 4.1% received H2RB, 1.9% received both, and 11.5% received neither.

- in the H2RB group, 63.6% received H2RB, 20.1% received PPI, 5.1% received both, and 11.2% received neither.

- Thus, 4.1% of PPI group patients got H2RBs and 20.1% of H2RB group patients received PPI

- The primary outcome was 90-day mortality. Is this long enough to determine a benefit or otherwise? Although challenging, having a longer end-point would have added confidence in my decision-making of one agent over another.

- The median time in the ICU was 2.8 days (range 1.2 – 5.7 days) in PPI group and 2.7 days (range 1.2 – 5.8 days) in the H2RB group. This may not have been enough days to find a meaningful difference in mortality

- The exclusion of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding may have been overzealous, with some patients actually having lower as opposed to upper tract bleeding.

- This study did not show an increase association of PPI use and C. difficile infection, but in this study if infection was not suspected, appropriate specimens were not sent and actual cases of infection may have been missed

- The association of PPIs and other infections (such as nosocomial pneumonia) was not evaluated in this study, therefore this cannot be ruled out as a possibility

- Data was obtained from registries – these can be prone to input error and hence could affect the results of this study

- There was no blinding of treatment choice for the clinicians or research staff. This can introduce bias.

- Country specific differences in rates of gastrointestinal hemorrhage could have affected outcomes

- Types of PPI or H2RB and their route of administration were left to the individual clinician – it is unclear whether this could influence outcomes

Discussion:

- In addition to non-blinding, there was an asymmetric non-adherence of medications with more physicians not using H2RBs and more cross over to PPIs. This is important for two reasons:

- If PPIs increase mortality, a high non-adherence rate could reduce what may have been a statistically significant increase in mortality

- But…if the use of PPIs reduced the risk of stress ulceration and improved survival in select subset of patients and physicians correctly identified these patients and gave them PPIs instead of the assigned H2RB, this would decrease mortality in the H2RB group

- None of the primary or secondary outcomes were statistically significant, but clinical trends show that fewer patients had clinically important upper gastrointestinal bleeds with PPIs (between group difference of 0.5%). This should be balanced with the clinical trend of increased 90-day mortality with PPIs (between group difference of 0.8%) as well as increased mortality in patients with higher severities of illness

Authors’ Conclusions:

“Among ICU patients requiring mechanical ventilation, a strategy of stress ulcer prophylaxis with use of proton pump inhibitors vs histamine-2 receptor blockers resulted in hospital mortality rates of 18.3% vs 17.5%, respectively, a difference that did not reach the significance threshold. However, study interpretation may be limited by crossover in the use of the assigned medication.”

Clinical Take Home Point:

- This is a good attempt at trying to answer a clinically-relevant question for intensivists (and ED physicians who are having to manage ICU boarders for a longer period of time). The authors attempted to achieve statistical power through a huge number of included patients, and generalizability by recruiting across many nations in multiple ICUs. Ultimately, the interpretation of the data was limited due to the nonadherence to the study protocol and the use of registry data for their analysis.

- Even though there may be lower rates of gastrointestinal bleeding in the PPI group, there is no statistically significant reason in terms of mortality to use PPI over H2RB (and there may in fact be some more harm in using PPIs).

- For the time being, we should continue to use H2RBs as the primary agent for stress ulcer prophylaxis in mechanically ventilated ICU patients.

References:

- Krag M et al. Prevalence and outcome of gastrointestinal bleeding and use of acid suppressants in acutely ill adult intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 2015 PMID: 25860444

- Barbateskovic M et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors or histamin-2 receptor antagonists in adult intensive care patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Intensive Care Med 2019 PMID: 30680444

- MacLaren R et al. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists vs proton pump inhibitors on gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage and infectious complications in the intensive care unit. JAMA Inten Med 2014 PMID: 24535015

- Young PJ et al. Effect of stress ulcer prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors vs histamine-2 receptor blockers on in-hospital mortality among ICU patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation: The PEPTIC randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020 PMID: 31950977

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- Emlyn’s: JC – The PEPTIC Study PPI vs H2RBs on the ICU

- PulmCrit: An Alternative View of the PEPTIC Trial

- The Bottom Line: PEPTIC

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Please Pass the Antacids – Will PEPTIC Change our Approach to ICU Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis? appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.