Introduction: Beyond the Data

Introduction: Beyond the Data

The evolution from eminence-based to evidence-based care has come to define bedside emergency medicine, with rigorous skepticism and scholarly consideration accelerated by the power of global connectivity. Where anecdote and opinion once drove therapy, clinicians now approach clinical conundrums with deliberate reflection, expecting—and at times demanding–ever-higher proof of perfection prior to implementing or incorporating therapies, tests, or approaches into their own practice. Such cogitation ensures excellence and safety and avoids pitfalls of over-adoption or confounding. Unfortunately, so many of our daily decisions are made in a space devoid of definitive data, and require a synthesis of relevant literature with our accumulated knowledge and experience—a departure from evidence-based medicine into the pragmatic world of evidence-informed medicine. It is only at this precipice—where studies and statistics simply don’t exist—that we change, where we push forward the boundaries of care, and develop not only experience, but the very questions which will define the next advances in emergency medicine. It’s with this in mind that we present this REBEL post, an entry not so much a look back on manuscripts which dictate our practice, but a treatise to help us look forward. To not inform, but to inspire thought and inquiry.

REBEL Cast Ep61 – Diagnostic Questions in Urinary Tract Infections in the Elderly

Background: Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is a microbiologic diagnosis, when >10^5 cfu/mL bacteria are identified in 2 consecutive voided urine specimens (only 1 specimen needed for males). It’s incredibly common, present in greater than 20% of healthy elderly community-dwelling women, as high as 50% in institutionalized elderly females, and 100% in patients with indwelling catheters (Nicolle 2014).

The clinical conundrum of the abnormal urinalysis in an elderly patient presenting with non-specific symptoms is a common occurrence. While it is well-known that urinary tract infections can cause malaise and mental status changes in elderly populations, consistent clinical data suggest that the overwhelming percentage of “positive” UAs represent asymptomatic bacteriuria, and are not truly indicative of UTI nor related to the patient’s non-specific complaints (Caterino 2018). Knowing that antibiotic treatment is of no value in patients with simple asymptomatic bacteriuria, we strive to limit such unnecessary antimicrobials, however parsing which UAs represent constitution-influencing infection and which are simple asymptomatic bystanders is a task not easily achieved in the ED, particularly when the patient lacks the cognitive or physical ability to relay typical symptoms such as dysuria, urinary frequency, or hesitancy.

Background: Systemic Immune Response

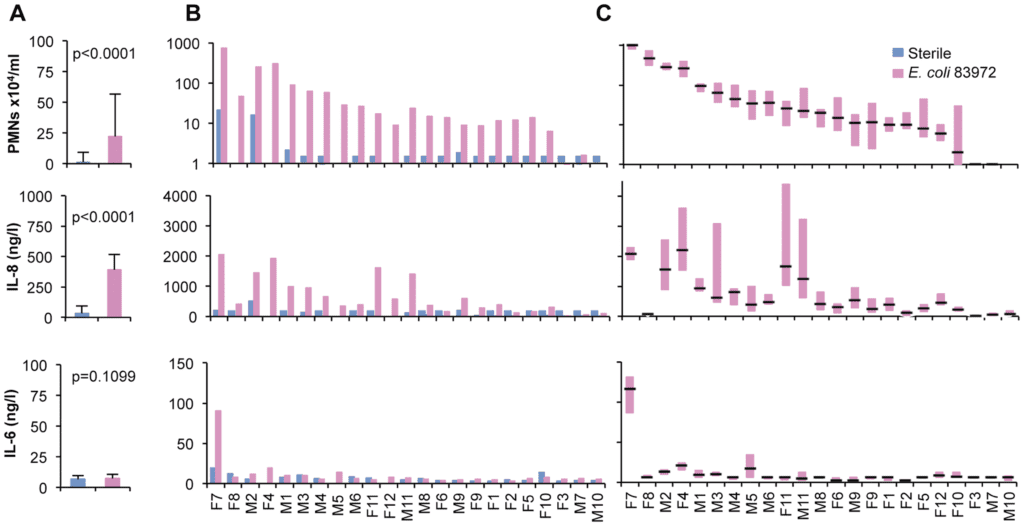

Recognizing the difficulty in distinguishing true infection from asymptomatic bacteriuria, multiple authors have attempted to investigate differences in systemic immune response among these cohorts. In 2011, a group of researchers compared the levels of various inflammatory markers in urine samples before and after inoculation with E. coli, noting that while WBCs and PMNs increased substantially (a phenomenon we witness daily at the bedside), levels of IL-6, an inflammatory cytokine more specifically indicated in systemic disease, remained unchanged (Hernandez 2011). The authors suggested their findings indicated a less vigorous host immune response among patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria than with symptomatic infection.

Figure 1. Inflammatory marker response in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Hernandez et al, 2011.

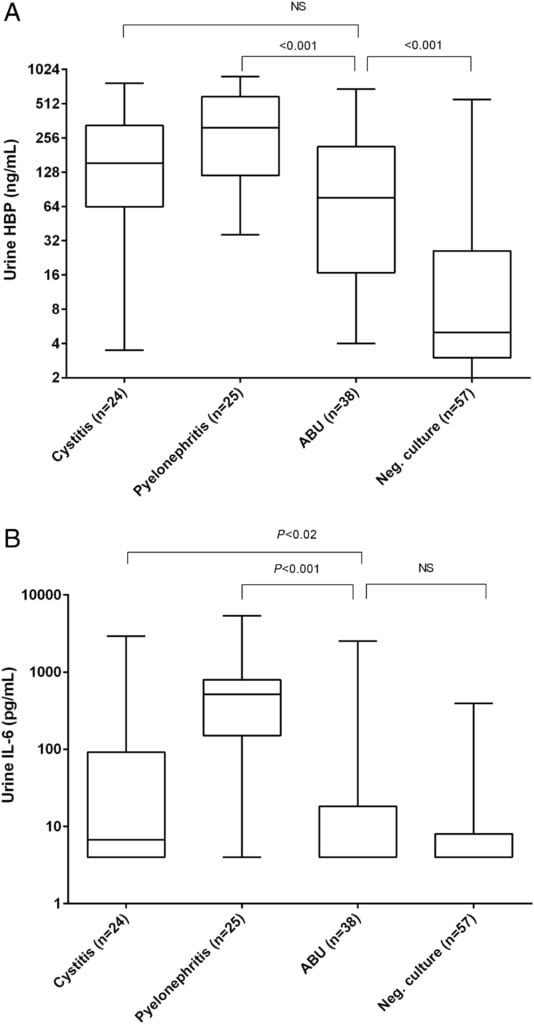

A 2016 investigation enrolled asymptomatic elderly nursing home residents and matched them with patients living in the community or at nursing homes with symptomatic UTI. Urinary IL-6, but not urinary heparin-binding protein (HBP), reliably distinguished between patients with cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria, adding further to the growing observational dataset that there is a fundamental and measurable difference in the body’s immune reaction in cases of true infection (Kjolvmark 2016).

Figure 2. Urinary HBP concentrations Figure 3. Urinary IL-6 concentrations

Procalcitonin

Enter procalcitonin, the latest diagnostic darling in inpatient circles. Procalcitonin (the biologic precursor to calcitonin) rises quickly and reliably in the setting of bacterial infection (Quadir 2018)(Memar 2017)(Taggart 2016). Dozens of trials have reliably demonstrated the test’s strong performance in decision support for antibiotic initiation or cessation, however in the most salient ED investigation—the ProACT Trial—procalcitonin failed miserably in limiting unnecessary antibiotic utilization (Huang 2018). Notably, however, such failure seemed more a function of clinician fears of untreated infection than a shortcoming of the test itself, an idiosyncrasy that was noted many times over in a slew of editorials following publication of ProACT. As many respondents argued–and the trial authors seemed to agree with—the combination of this reassuring objective test with a concerted effort to limit unnecessary antibiotic use, or an antibiotic stewardship program, could be more effective in harnessing the diagnostic value of procalcitonin (Bremmer 2018).

Such application—a considered and nuanced synthesis of this inflammatory marker in a well-defined clinical context—jibes with a vibrant body of literature suggesting a role for procalcitonin in the diagnosis of true urinary tract infection. Procalcitonin reliably rose with worsening urinary tract disease in one bench study (Xu 2014), and in one comprehensive review was found to be a “key marker” in children with UTI (Leroy 2011). When operationalized, serum procalcitonin was a good predictor of disease severity in a meta-analysis of pediatric trials (Mantadakis 2009).

A Dose of Reality

Despite compelling data that treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria lacks benefit, and growing evidence that non-specific symptoms in the elderly are generally not caused by urinary tract infections, these patients overwhelmingly have broad spectrum agents initiated in the emergency department or upon admission to the hospital. Often, it’s too difficult to parse out when antibiotics are appropriate, and serious concerns about disease progression or missed metrics dominate the diagnostic framework. Even when restraint wins out in the ED, the diagnostic equipoise often drives inpatient teams to start antibiotics. Even more striking, well-done surveys demonstrate that nearly half of respondents prescribe antibiotics despite knowing a urinalysis demonstrates asymptomatic bacteriuria and not true infection (Lee 2015). When clinicians are unable to elicit information on lower urinary tract symptoms from elderly patients with dementia, advanced cerebrovascular disease, or other impairments creating communication barriers, they are likely to initiate antimicrobial therapy in a well-intentioned effort to prevent progression and worsening infectious outcomes, and anecdote of improvement perpetuates such practice (Miller 2001).

A Modest Proposal

The management morass of abnormal urinalyses in the elderly patient with nonspecific symptoms may represent an excellent opportunity for utilization of procalcitonin testing—using an evidence-informed approach as a lifesaver in a sea of uncertainty and clinical shortcomings. By the very nature and ambiguity of asymptomatic bacteriuria, a de-facto antibiotic stewardship effort is already underway in every hospital across the country, as well-meaning physicians strive to separate true infection from asymptomatic distractors.

Where clinical complacency exists—an afebrile, non-toxic-appearing patient in whom the desire to spare unnecessary antibiotic use conflicts with the compulsion to not allow an indolent infection run rampant—a procalcitonin-augmented strategy might satisfy both imperatives.

Such a strategy is not novel. Published recently in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, one retrospective analysis of UTIs found a negative predictive value of 91% for a low procalcitonin, arguing strongly for its use as an adjunct in the non-initiation of empiric antibiotics (Levine 2018). Even more compelling, a randomized trial of nearly 200 emergency department patients found that a procalcitonin-based algorithm reduced antibiotic exposure by 30% without negative effects on clinical outcomes (Drozdov 2015). The introduction of procalcitonin in these departments served as a reliable and objective diagnostic waypoint and limited costly, harmful, and unnecessary antibiotics.

Conclusion

No current rigorous trial has yet examined procalcitonin’s performance in this narrow and nuanced framework, but the collated and considered information available to use suggests that adding this simple test may provide a much-needed diagnostic beacon and potentially lead to better care in real-world applications.

References

- Freedman L.R. Chronic pyelonephritis at autopsy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1967;66:697–710. PMID: 6023536

- Kass E.H. Pyelonephritis and bacteriuria. A major problem in preventive medicine. Ann. Intern. Med. 1962;56:46–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-56-1-46. PMID: 14454174

- Nicolle, Lindsay E. “The paradigm shift to non-treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria.” Pathogens5.2 (2016): 38. PMID: 27104571

- Nicolle, Lindsay E. “Asymptomatic bacteriuria.” Current opinion in infectious diseases 27.1 (2014): 90-96. PMID: 24275697

- Caterino, Jeffrey M., et al. “Nonspecific Symptoms Lack Diagnostic Accuracy for Infection in Older Patients in the Emergency Department.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (2018). PMID: 30467825

- Hernández, Jenny Grönberg, et al. “Genetic control of the variable innate immune response to asymptomatic bacteriuria.” PLoS One 6.11 (2011): e28289. PMID: 22140570

- Kjölvmark, Charlott, et al. “Distinguishing asymptomatic bacteriuria from urinary tract infection in the elderly–the use of urine levels of heparin-binding protein and interleukin-6.” Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease85.2 (2016): 243-248. PMID: 27039283

- Quadir, Ashfaque F., and Philip N. Britton. “Procalcitonin and C‐reactive protein as biomarkers for neonatal bacterial infection.” Journal of paediatrics and child health 54.6 (2018): 695-699. PMID: 29667256

- Memar, Mohammad Yousef, et al. “Procalcitonin: The marker of pediatric bacterial infection.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 96 (2017): 936-943. PMID: 29203386

- Taggart, K., and S. Nielsen. “Procalcitonin as a Biomarker of Bacterial Infection.” South Dakota medicine: the journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association 69.8 (2016): 370. PMID: 28806006

- Huang, David T., et al. “Procalcitonin-Guided Use of Antibiotics for Lower Respiratory Tract Infection.” New England Journal of Medicine(2018). PMID: 29781385

- Bremmer, Derek N., Nathan R. Shively, and Thomas L. Walsh. “Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Use.” The New England journal of medicine 379.20 (2018): 1972. PMID: 30439286

- Xu, Rui-Ying, et al. “Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in urinary tract infection diagnosis.” BMC urology 14.1 (2014): 45. PMID: 24886302

- Leroy, Sandrine, and Alain Gervaix. “Procalcitonin: a key marker in children with urinary tract infection.” Advances in urology 2011 (2011). PMID 21274426

- Mantadakis E, Plessa E, Vouloumanou EK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Chatzimichael A, Falagas ME. Serum procalcitonin for prediction of renal parenchymal involvement in children with urinary tract infections: a meta-analysis of prospective clinical studies. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155(6):875–881.e1. PMID: 19850301

- Lee, Myung Jin, et al. “Why is asymptomatic bacteriuria overtreated?: A tertiary care institutional survey of resident physicians.” BMC infectious diseases 15.1 (2015): 289. PMID: 26209977

- Miller, John. “To treat or not to treat: managing bacteriuria in elderly people.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 164.5 (2001): 619-619. PMID: 11258205

- Levine, Alexander R., et al. “Utility of initial procalcitonin values to predict urinary tract infection.” The American journal of emergency medicine (2018). PMID 29530360

- Drozdov, Daniel, et al. “Procalcitonin and pyuria-based algorithm reduces antibiotic use in urinary tract infections: a randomized controlled trial.” BMC medicine 13.1 (2015): 104. PMID 25934044

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim R. Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post REBEL Cast Ep 61: Diagnostic Questions in Urinary Tract Infections in the Elderly appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.