Friday, 2300 hours:

Friday, 2300 hours:

A 24 year-old woman presents to your Emergency Department after a motor vehicle collision. She was the restrained driver of a car that collided head-on with another vehicle. She is complaining only of chest pain and appears uncomfortable and anxious. The monitor shows sinus tachycardia and you spot a sternal fracture on her chest x-ray. After IVF and Fentanyl, she remains slightly tachycardic and you wonder:

- Do I need to send a troponin?

- If the troponin is negative does this patient need to be admitted?

- What other testing should I consider in the Emergency Department?

Blunt Cardiac Injury

Definition: There is no standard definition of blunt cardiac injury (BCI). In general, BCI refers to any blunt trauma to the heart. This can range from mild to severe injuries including:

- Cardiac contusions

- Dysrhythmias after trauma

- Ventricular wall rupture

Epidemiology:

- Estimated incidence of BCI in thoracic trauma varies greatly with reported values ranging from 8 to 71%. This large range results from a lack of clear definition and diagnostic criteria. (Pasqaule 1998, Singh 2018)

- One recent study found a BCI incidence of 25% among patients with blunt thoracic trauma. (Emet 2010)

-

Most commonly injured anatomy (Anterior Structures):

- Right ventricle

- Right atrium

-

Less commonly injured:

- Left ventricle and atrium

- Septum, valves, and coronary arteries (extremely RARE). (Karalis 1994)

Causes:

Suspect BCI in any patient with significant thoracic trauma or direct precordial impact including:

- Motor vehicle accidents (most common)

- Pedestrians struck by motor vehicles

- Crush injuries

- Blast injuries

- Deceleration injuries

A significant amount of force is normally required for BCI to occur. Up to 20% of death due to motor vehicle crashes is attributed to BCI. (Schultz 2004, Singh 2018)

A word (or two) in Latin…

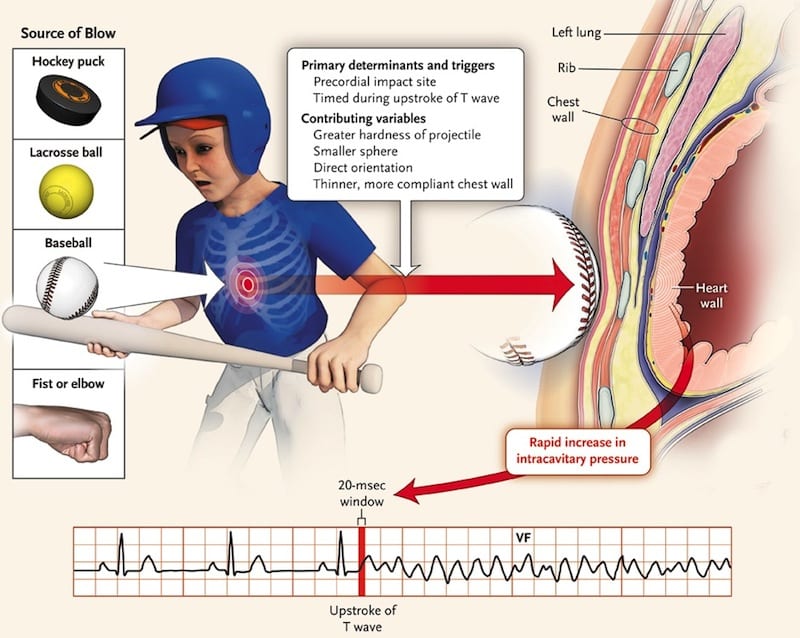

Commotio Cordis (Borjesson 2009)

- Latin for “disturbance of the heart”

- Second leading cause of death in young athletes after hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

-

Sudden death after a seemingly low-impact blow to the chest by a hard projectile most commonly

- Baseballs

- Lacrosse balls

- Hockey pucks

- The fatal nature of the blow requires an unlucky combination of impact location, velocity, and projectile hardness occurring just milliseconds before the peak of a T wave

- This results in ventricular fibrillation followed by sudden death

Pathophysiology:

The pathophysiology of BCI depends upon which of the injuries has occurred

- Pericardial injury:Pericardial laceration, perforation, hematoma

- Atrial and Ventricular injury

- Wall rupture

- Myocardial contusions (most common and most innocuous)

- Valvular injury: Cardiac valve, papillary muscle, and chordae tendineae tears or ruptures

- Coronary vessel injury

- Intimal disruption

- Thrombosis

- Dissection

Signs & Symptoms:

-

Symptoms:

- Most common symptom is chest pain

- Symptoms will widely depend on the extent of BCI

-

Signs:

- Dysrhythmias (most commonly sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation)

- Chest wall deformities or ecchymosis

- Pulse deficits

- Hypotension

- New murmurs

-

New heart failure

- Rales

- Muffled heart sounds

- Distended neck veins

- Pericardial effusion or tamponade

The most severe BCIs result in wall rupture in any of the chambers and these patients typically do not survive to ED presentation. (Shorr 1987, Calhoon 1986, Yousef 2014)

Pediatric patients have increased compliance of the thoracic cavity and there may be no outward signs of trauma to raise suspicion of BCI.

Associated Injuries (Schultz 2004):

- Head injury

- Extremity injury

- Rib fracture

- Aortic injury

- Hemothorax

- Pulmonary contusion

- Pneumothorax

- Flail chest

- Sternal fracture

- Abdominal solid organ injury

- Spinal injury

Immediate Management:

- Clinicians should proceed with initial stabilization of the trauma patient

- Hypotension in the trauma patient should be initially approached as due to hemorrhage rather than from a purely cardiac cause

- A FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) exam should be performed immediately after the primary survey is completed

- Consider an “Extended” exam (EFAST) and include views of the anterior thorax to evaluate for pneumothorax

- Persistent tachycardia after volume resuscitation, adequate pain control, and exclusion of intrathoracic or intraabdominal hemorrhage should raise suspicion of possible BCI

Testing and Treatment:

-

Electrocardiogram

- 12-lead EKG is an important screening tool in the patient with potential BCI and can quickly guide the patient’s disposition

-

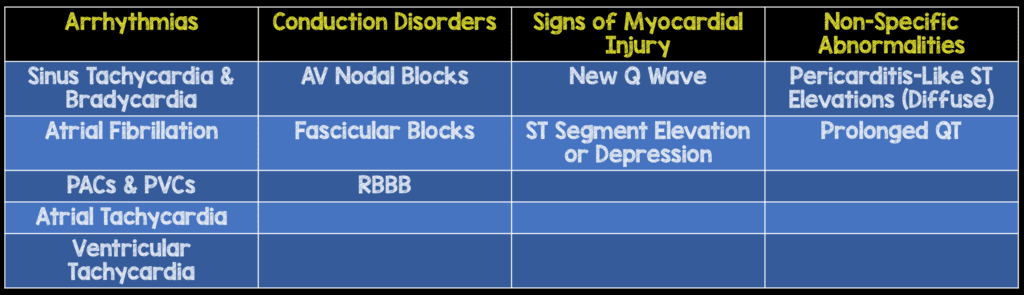

New abnormalities on EKG such as

- Dysrhythmias (i.e. atrial fibrillation)

- Conduction delays (bundle branch blocks)

- ST segment elevations or depressions warrant continued telemetry monitoring

-

- The most common rhythm encountered after BCI is sinus tachycardia followed by atrial fibrillation

- EKGs should be repeated with any change in the patient’s symptomatology or hemodynamic status

EKG Findings in Blunt Cardiac Injury (Foil 1990):

-

Chest X-ray

- Helpful initial test to evaluate thoracic trauma

-

Certain injuries visible on x-ray are commonly associated with but do not guarantee BCI:

- Sternal fractures (Sadaba 2000)

- Multiple rib fractures

-

Echocardiography

- Part of a comprehensive evaluation for BCI

- Pericardial effusions and tamponade should be ruled out early with FAST exam

-

Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE)

- Can be performed at the bedside by EM physicians

-

Provides an impression of:

- Overall cardiac contractility (organization, ejection fraction)

- Wall motion abnormalities

- Turbulent blood flow

- Intraventricular or intraatrial thrombi

- Visualization limited in up to 1/3 of patients due to poor echocardiographic views

- Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) is more sensitive in detecting injuries that require intervention (wall and valve ruptures)

- Time to surgery was significantly shorter for patients with BCI identified on TEE. (Chirillo 1996)

- TTE should be repeated with any change in the patient’s status (Chirillo 1996, Labovitz 2010)

-

Cardiac biomarkers

- Utility of cardiac biomarkers such as troponin remains unclear

- Presence of a single elevated troponin does little to help guide further management or intervention except for increasing the likelihood of admission and cardiology consultation

- Optimal timing for troponin measurement remains unknown

- A review of prospective studies demonstrated that a negative troponin had 100% negative predictive value for subsequent cardiac complications (Guild 2014). However, the ideal timing of checking that troponin is unknown

- Elevations in troponin can also be attributed to significant non-thoracic trauma

- CK-MB is not a recommended biomarker in BCI and has not been shown to correlate with morbidity or mortality from BCI (Fulda 1997)

- There is no gold standard or recommendation for the routine use of cardiac biomarkers to characterize or prognosticate BCI

-

Chest Computed Tomography (CT)

- CT with significant thoracic trauma raises the suspicion for BCI and should lead to further investigations

- CT is not sensitive as it has been shown to miss injuries then found on echo (Hammer 2016)

Published Guidelines:

- The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) published a set of guidelines for the evaluation and care of those with BCI: (Clancy 2012)

-

Level 1 Evidence:

- Obtain an electrocardiogram (EKG) on all patients with suspected BCI

-

Level 2 Evidence:

- If the EKG reveals a new abnormality (dysrhythmia, ST changes, heart blocks), admit the patient for continuous EKG (telemetry) monitoring. Compare to a previous EKG whenever available

- BCI can be ruled out in patients with a normal EKG and a negative troponin I although the optimal timing of troponin measurement remains undetermined

- Obtain an optimal TTE or a TEE on patients who are hemodynamically unstable or with persistent new arrhythmias

- Those with sternal fractures but also with a normal EKG and troponin I do not have to be continuously monitored

- Troponin I are the preferred cardiac enzymes. Creatinine phosphokinase levels are not useful

- Nuclear studies offer little when compared with Echocardiography and do not need to be obtained routinely

- Level 3 Evidence:

-

Among patients with BCI, surgery is not contraindicated, given appropriate monitoring in

- The elderly with known cardiac disease

- Hemodynamically unstable patients

- Those with new EKG abnormalities on admission

- Measure troponin I on patients with suspected BCI. If elevated, admit to a monitored setting and follow serial troponins although the best timing of measurement has not been determined

- Cardiac CT or MRI can be useful in differentiating acute MI from BCI to help guide further management

Take Home Points

- No single test can be used to exclude BCI. However a thorough physical exam combined with a 12-lead EKG, troponin measurement, and echocardiography can be used to characterize BCI and direct care

- Obtain a 12-lead EKG in all thoracic trauma patients

- A chest x-ray may help to identify associated injuries. However, isolated musculoskeletal injuries such as sternal fractures do not correlate with a risk of BCI

- Bedside TTE can quickly evaluate for life-threats such as cardiac tamponade; A TEE is both sensitive and specific across the spectrum of BCI pathology and is part of a comprehensive evaluation

- BCI can be excluded in a patient without EKG abnormalities and a negative troponin I

Guest Post By:

Katrina D’Amore, MD

PGY-4 Resident

St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center Emergency Department

References:

- Schultz JM, Trunkey DD: Blunt cardiac injury. Crit Care Clin 2004; 20(1): 57-70. PMID: 14979329

- Pasquale M, Fabian TC: Practice management guidelines for trauma from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma 1996; 44: 941; Discussion 956. PMID: 9637148

- Singh S, Angus LD: Blunt Cardiac Injury. NCBI Bookshelf StatPearls 2018. PMID: 30335300

- Emet M, et al: Assessment of cardiac injury in patients with blunt chest trauma. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2010; 36 (5): 441-7. PMID: 26816225

- Shorr RM, et al: Blunt thoracic trauma. Analysis of 515 patients. Ann Surg 1987; 206: 200. PMID: 3606246

- Calhoon JH, et al: Management of blunt rupture of the heart. J Trauma 1986; 26: 495. PMID: 3723615

- Borjesson M, Pelliccia A: Incidence and aetiology of sudden cardiac death in young athletes: an international perspective. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43: 644. PMID: 19734497

- Rodriguez A, Turney SZ: Blunt injuries of the heart and pericardium, in Turney SZ, et al (eds) Management of Cardiothoracic Trauma. Baltimore MD, Williams & Wilkins, 1990.

- Tenzer ML: The spectrum of myocardial contusion: a review. J Trauma 1985; 25: 620. PMID: 2989545

- Yousef R, Carr JA: Blunt cardiac trauma: a review of the current knowledge and management. Ann Thoracic Surg 2014; 98 (3): 1134-40. PMID: 25069684

- Foil MB, et al: The asymptomatic patient with suspected myocardial contusion. Am J Surg 1990; 160: 638 discussion 642. PMID: 2252127

- Sadaba JR, et al: Management of isolated sternal fractures: determining the risk of blunt cardiac injury. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000; 82: 162-66. PMID: 10858676

- Clancy K, et al: Screening for blunt cardiac injury: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73(5) Supplement 4. PMID: 23114485

- Salim A, et al: Clinically significant blunt cardiac trauma: role of serum troponin levels combined with electrocardiographic findings. J Trauma 2001; 50: 237. PMID: 11242287

- Edouard AR, et al: Circulating cardiac troponin I in trauma patients without cardiac contusion. Intensive Care Med 1998; 24: 569. PMID: 9681778

- Guild CS, et al: Negative predictive value of cardiac troponin for predicting adverse cardiac events following blunt chest trauma. South Med J 2014; 107(1): 52-6. PMID: 24389788

- Reid CL, et al: Chest trauma: evaluation by two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J 1987; 113: 971. PMID: 3565247

- Hiatt JR, et al: The value of echocardiography in blunt chest trauma. J Trauma 1988; 28(7): 914-22. PMID: 3398089

- Chirillo F, et al: Usefulness of transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography in recognition and management of cardiovascular injuries after blunt chest trauma. Heart. 1996;75(3):301. PMID: 8800997

- Karalis DG, et al: The role of Echocardiography in blunt chest trauma: a transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Trauma 1994; 36: 53. PMID: 8295249

- Labovitz AJ, et al: Focused cardiac ultrasound in the emergent setting: a consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and American College of Emergency Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010; 23 (12): 1225. PMID: 21111923

- Nagy KK, et al: Determining which patients require evaluation for blunt cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma. World J Surg 2001; 25(1): 108-11. PMID: 11213149

- Fulda GJ, et al: An evaluation of serum troponin T and signal-averaged electrocardiography in predicting electrocardiographic abnormalities after blunt chest trauma. The Journal of trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 1997; 43(2): 304-12. PMID: 9291377

- Hammer MM, et al: Imaging in blunt cardiac injury: Computed tomographic findings in cardiac contusion and associated injuries. Injury 2016; 47(5): 1025-30. PMID: 26646729

- Agarwal D, Chandra S: Challenges in the diagnosis of blunt cardiac injuries. Indian J Surg 2009; 71: 245-53. PMID: 23133167

- Bellal J, et al: Identifying the broken heart: predictors of mortality and morbidity in suspected blunt cardiac injury. Am J of Surg 2016; 211(6): 982-88. PMID: 26879418

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami) and Salim Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post Blunt Cardiac Injury (BCI) appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.