Background Information:

Electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation is regularly performed by emergency physicians, intensivists, and cardiologists. Although many approaches to performing this procedure exist, the most common electrode placement is the anterior-lateral compared to the anterior-posterior positioning.1 The literature backing this up comes from two studies that used monophasic defibrillators.2,3 A more recent meta-analysis that included studies using biphasic defibrillators didn’t have enough data to support one position over the other. As a result, the authors of this multicenter randomized trial sought to compare these two electrode positions.

Electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation is regularly performed by emergency physicians, intensivists, and cardiologists. Although many approaches to performing this procedure exist, the most common electrode placement is the anterior-lateral compared to the anterior-posterior positioning.1 The literature backing this up comes from two studies that used monophasic defibrillators.2,3 A more recent meta-analysis that included studies using biphasic defibrillators didn’t have enough data to support one position over the other. As a result, the authors of this multicenter randomized trial sought to compare these two electrode positions.

Paper: Schmidt AS, et al. Anterior-Lateral Versus Anterior-Posterior Electrode Position for Cardioverting Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2021 Dec 21. PMID: 34814700

Clinical Question:

- Which electrode position (anterior-lateral or anterior-posterior) is more effective for the biphasic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation when using energies escalating to maximum levels?

What They Did:

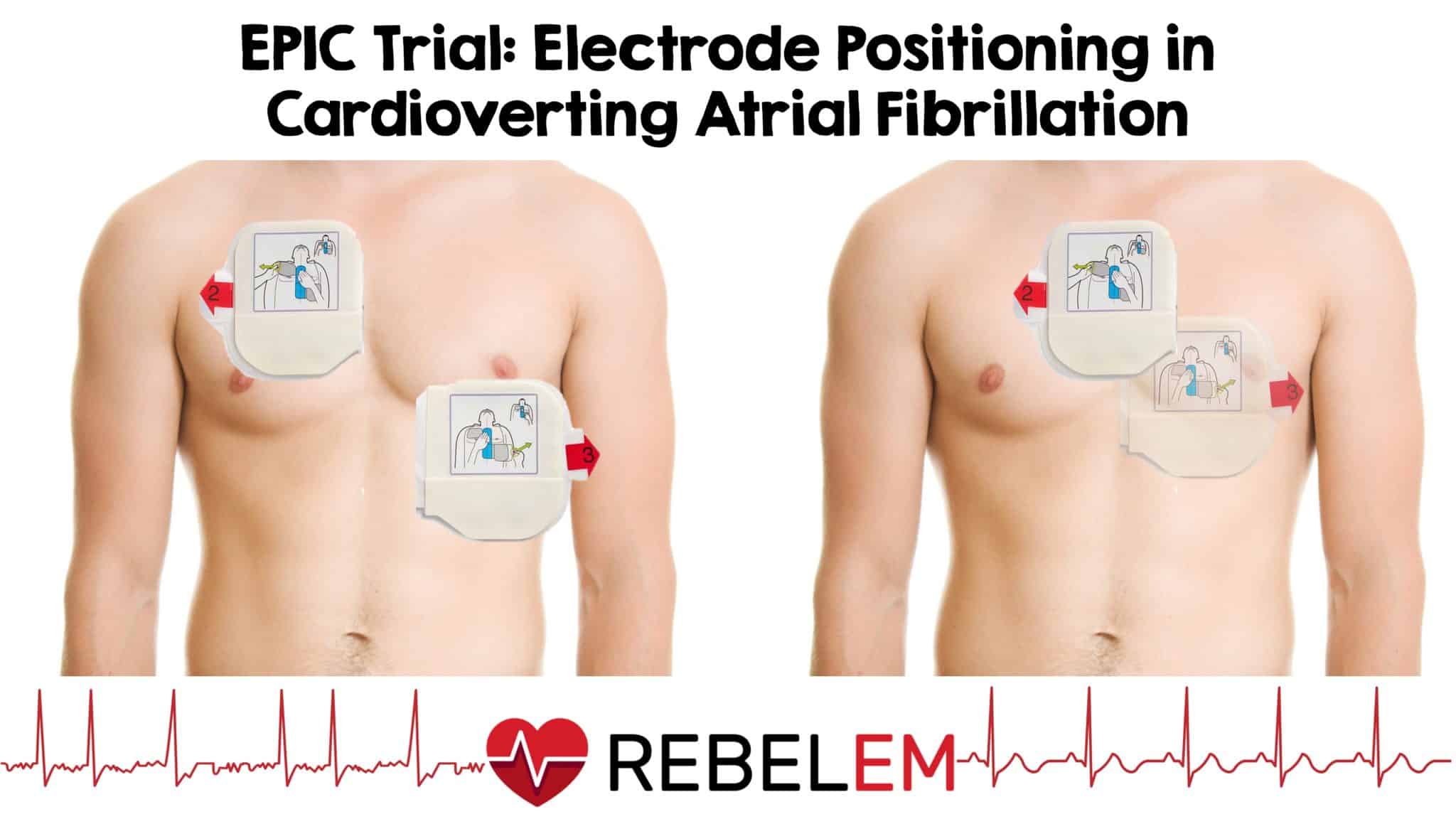

- Electrode Position in Cardioverting Atrial Fibrillation (EPIC)

- Multicenter, randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial performed in Denmark

- Patients were randomly assigned to one of the following two groups:

- Anterior-Lateral Electrode Positioning (ALE)

- Anterior-Posterior Electrode Positioning (APE)

- Clinician who performed the cardioversion was not blinded to the electrode position used

- Synchronized shocks were delivered by a defibrillator using a biphasic truncated exponential waveform (ie. Lifepak15 or 20 Defibrillator)

- Escalating energy shocks of 100 Joules, 150 J, 200 J and 360 J were delivered until sinus rhythm was restored or a up to a maximum of 4 shocks

- Patients were anesthetized using 1 mg/kg IV Propofol with additional subsequent doses of 20 mg if needed

Inclusion Criteria:

- Adult patients ( > 18 years of age)

- Had atrial fibrillation

- Scheduled for elective cardioversion

- Have received sufficient anticoagulation or a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) documenting the absence of intracardiac thrombi

Exclusion Criteria:

- Hemodynamically unstable

- Untreated hypothyroidism

- Known or suspected pregnancy

- Arrhythmias other than atrial fibrillation

- Implantable devices (Pacemaker or cardioverter device)

- Previously enrolled in trial

Outcomes:

Primary

- Proportion of patients in sinus rhythm 1 minute after the first shock

Secondary

- Proportion of patients in sinus rhythm 1 minute after the final cardioversion shock, up to a maximum of 4 cardioversion shocks

- Cardioversion efficacy at discharge 2 hours after cardioversion

Safety

- Number of patients with arrhythmic events (asystole, AV blocks, transient bradycardia, or ventricular arrhythmia) during or after cardioversion detected within 2 hours of continuous monitoring

- Skin redness under electrodes

- Patient reported pain or discomfort using a numeric rating scale from 0 to 10

Results:

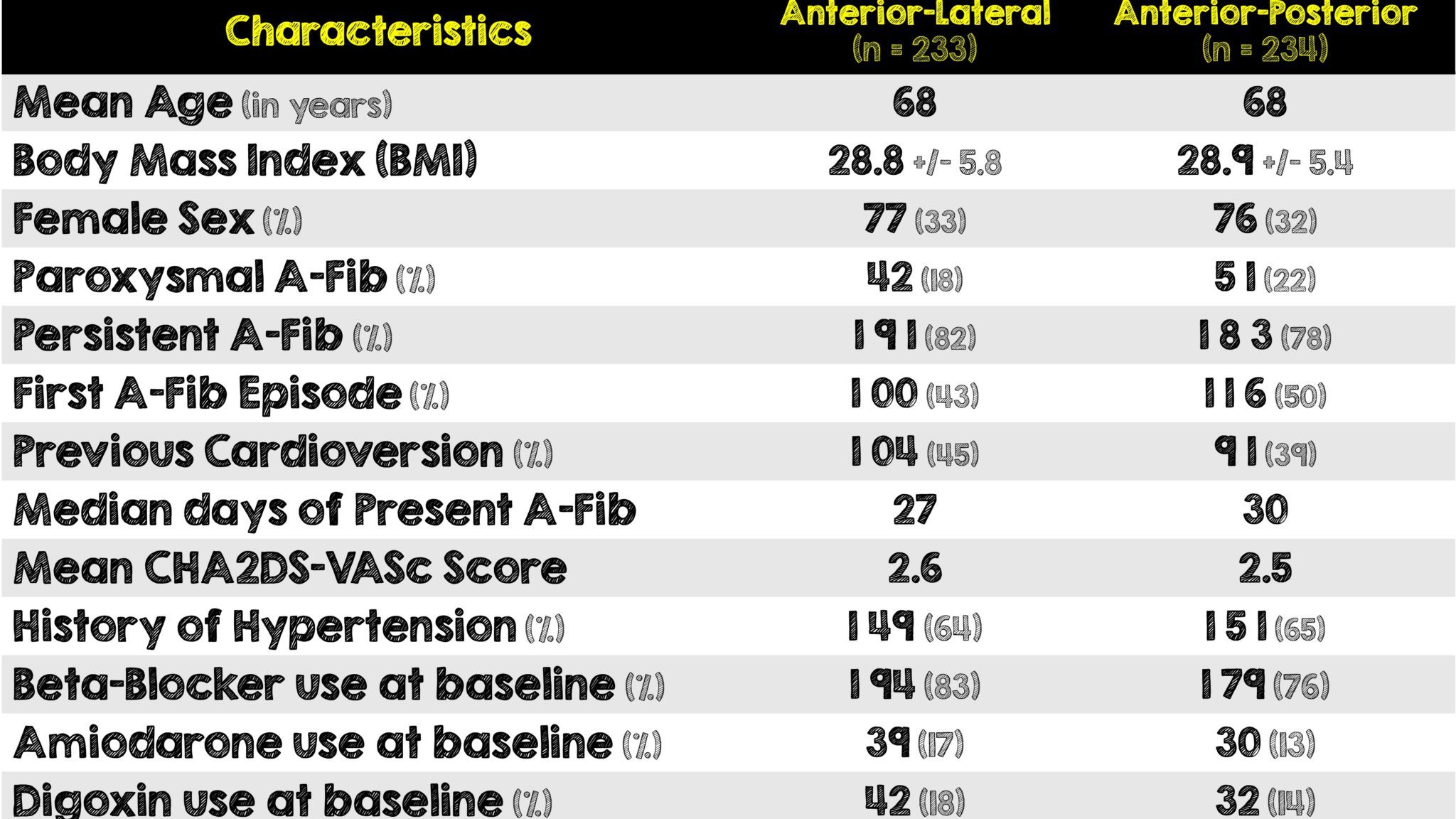

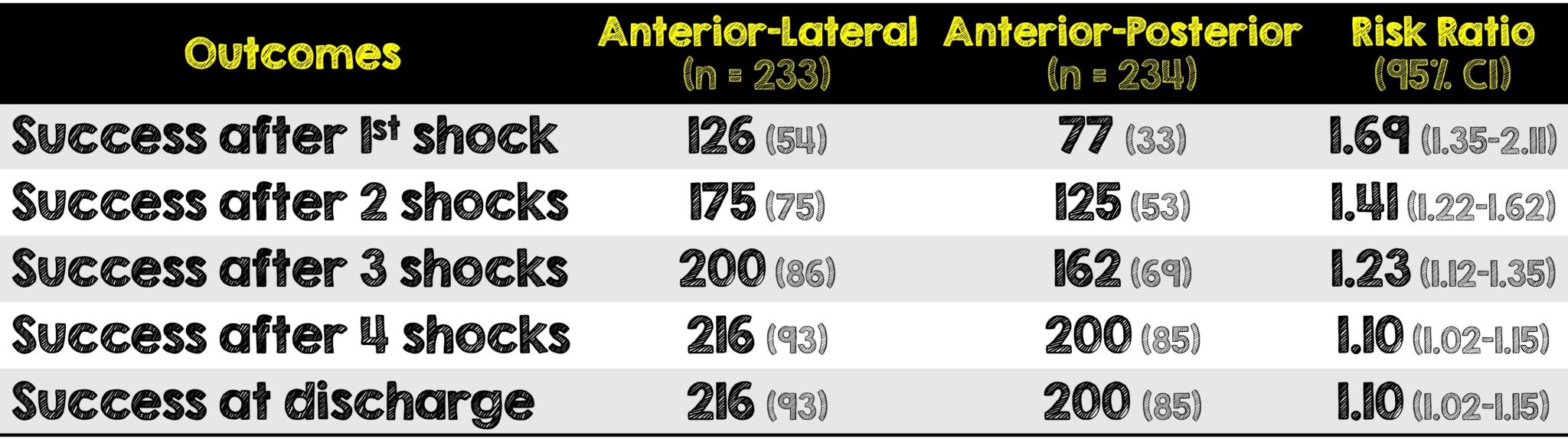

- 467 patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis

- There were 233 patients randomized to the ALE group and 234 to the APE group

Critical Results:

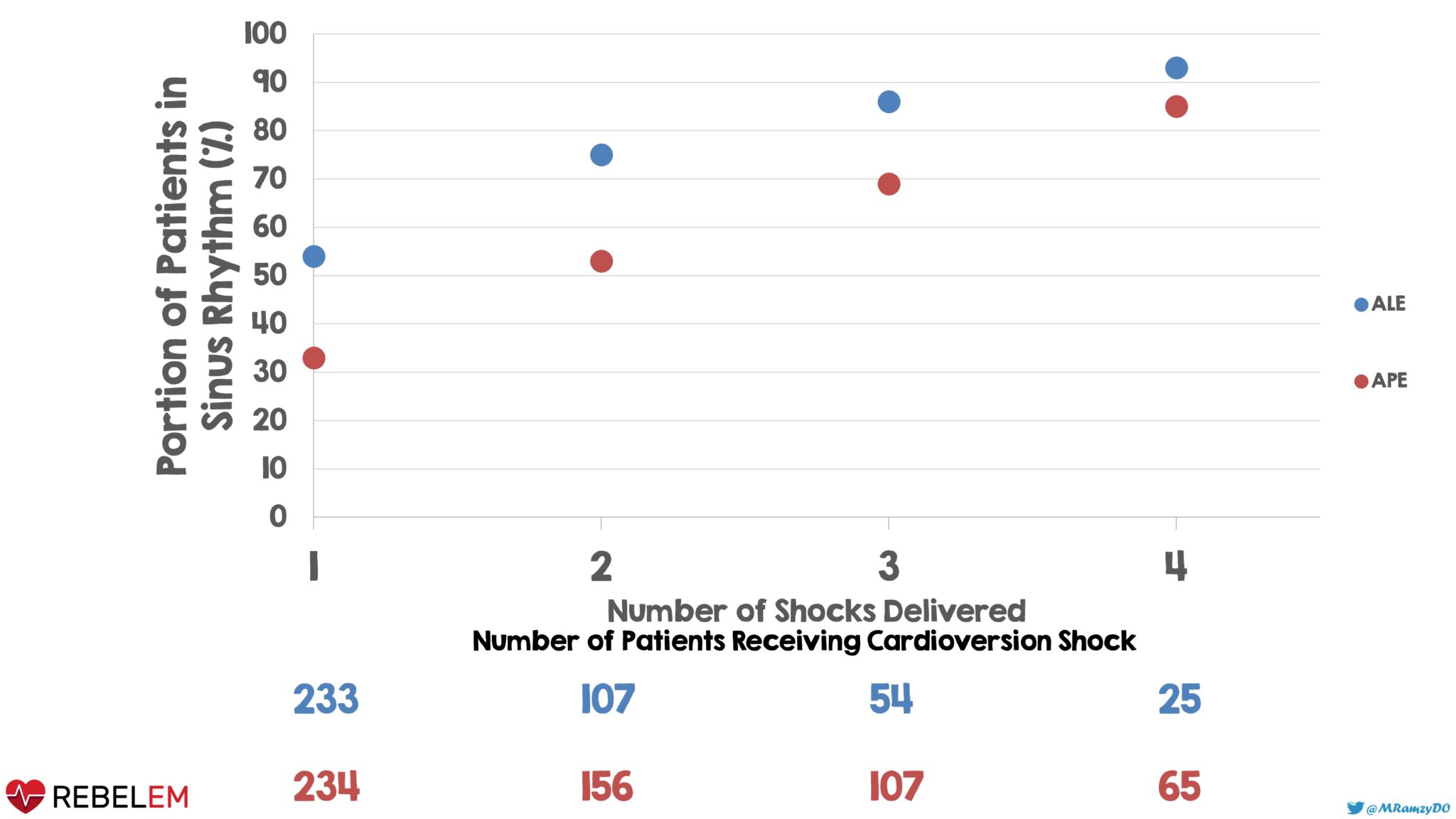

Graph 1: ALE significantly reduced the number of shocks when compared to APE

- 126 patients assigned to the ALE group had their atrial fibrillation converted to sinus rhythm within one minute after the first shock and had a p-value <0.001

- One patient assigned to the APE group developed an advanced 2:1 AV block requiring pacemaker implantation

- Two patients, one in each group, developed transient bradycardia which spontaneously resolved prior to discharge

- Risk difference after final shock for obese patients was 15 percentage points (95% CI, 5-25) with a risk ratio of 1.2 (95% CI, 1.05 – 1.36). For non-obese patients, the risk difference after the final shock was 3 percentage points (95% CI, -3 to 9) with a risk ratio of 1.03 (95% CI, 0.96 to 1.10)

Strengths:

- There were basically no protocol violations as 99% of enrolled patients received the assigned pad positioning

- No anti-arrhythmic drugs were used immediately before or after the cardioversion meaning this was a true test of pad positioning without medications as confounders

- Attempts to answer a clinically relevant question as anterior-posterior electrode positioning is not only most widely used but considered superior to anterior-lateral approach

- Primary outcome was consistent across predefined subgroups and thus further strengthening this trial’s results

- Included escalating energy levels to a maximum fixed-energy shock which during the conduction of the study became suggested in the European Guidelines

- Aside from a high proportion of males in the whole study, both groups were otherwise fairly well balanced

- Success rate in study was similar to other cardioversion studies

- Evaluated for important safety outcomes

Limitations:

- Different patient population than the emergency department or intensive care unit (ie. scheduled elective cardioversion with no known clot or already anticoagulated in a hemodynamically stable patient)

- Only evaluated two electrode positions as opposed to alternatives (right anterior-posterior or apex-anterior positions)

- Outcome based on success of sinus rhythm after only first shock

- Initially using maximum energy shocks may have resulted in a different outcome

- Treating clinician was not blinded to electrode positioning

- Performed only in one country that has universal / public healthcare which limits its external validity

- Included elective outpatient cardioversion getting anticoagulation or confirmed no cardiac thrombi thus limited application to the emergency department setting

- Utilized only one brand of defibrillator (LifePak vs Zoll vs Phillips)

Discussion:

- While the mechanisms behind pad positioning still require further investigation, it can be thought of intuitively based on physiology. APE positioning is selectively targeting the left atrium and hence originally thought to be more effective in converting A-fib whereas ALE’s vector is likely targeting more of the entire myocardium.

- There was a significant interaction on the effect of electrode position on the outcome of the final shock when obese patients (BMI > 30) were cardioverted compared to non-obese patients (BMI < 30). There was also a difference in patients with their first A-Fib episode vs patients with more than 1 episode of A-Fib.

- There’s differing practice behind how cardioversion should be attempted (ie. gradual increase in energy vs initial maximum amount in hopes of reducing the number of shocks needed to convert). The authors used the gradual increase method, however It’s very possible that the primary outcome of this study could have been different had they used initially maximum settings since it was only assessing success after that first shock. It’s worth noting they saw a significant difference when escalating to maximum energy.

- Additionally, it’s been shown that maximum fixed-energy shocks are more effective than escalating low-energy shocks. We’ve previously reviewed this before on a prior REBEL EM Post

- There are some practical reasons to also consider the ALE positioning as first line in cardioversion: First, ALE is convenient and possibly faster. Second, for transcutaneous pacing, ALE is more commonly used than APE.

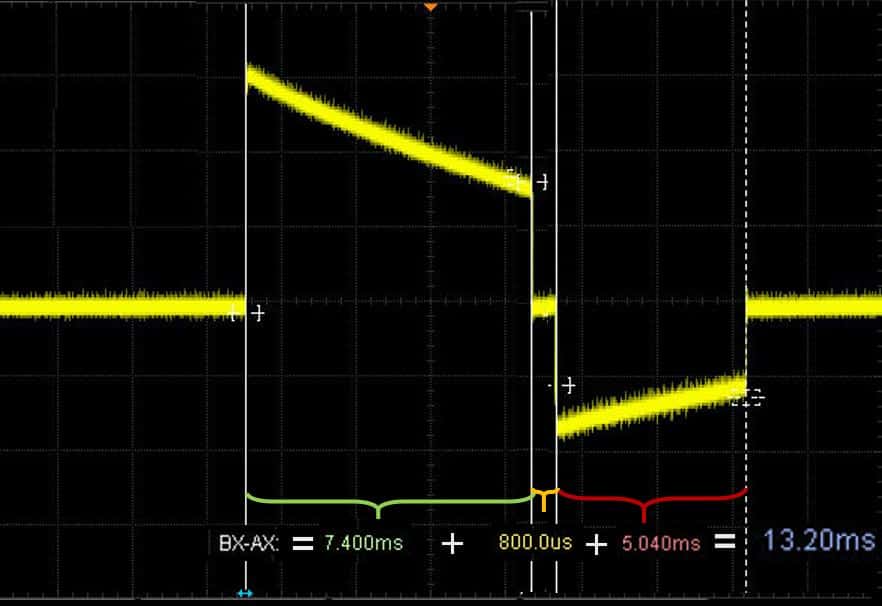

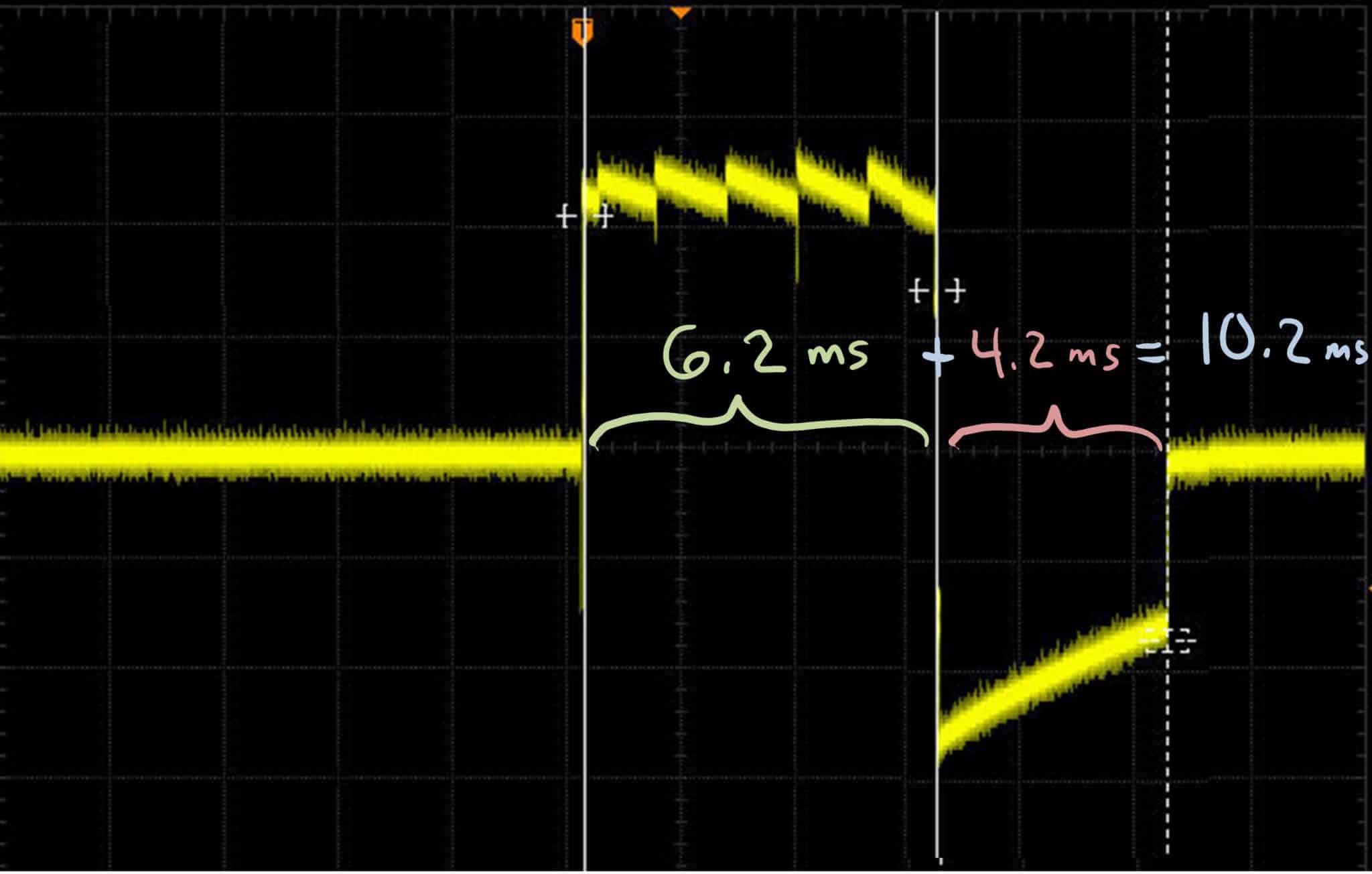

- Defibrillators vary widely based on the way they deliver a set charge. Some, like the LikePak used in this study, utilize a truncated high-peak waveform (Figure 1). Others like some brands of Zoll use a Rectilinear waveform (Figure 2).

- The high-peak waveform on the LifePak defibrillators may be better for cardioversion as a higher amount of energy is delivered upfront. Since the authors didn’t test any other defibrillators, we have no way (yet) of knowing if a particular waveform is better or more efficacious than another

- While the findings of this study are interesting, it’s difficult to apply this to patients in the emergency department for several reasons: they may or may not present hemodynamically stable, we often don’t know when their atrial fibrillation actually started, they are not on anticoagulation (unless for some other reason like PE) or had a TEE documenting the absence of an intracardiac thrombi

- The authors state it was not possible for the clinician performing the cardioversion to be blinded. This is a huge downside to this study in that it was unblinded and thus potentially increasing the bias. The authors definitely could have made this happen with some creative thinking and/or extra costs

- There is emerging literature investigating the utility of changing the pad location to alter the vector direction of defibrillation after one or more shocks fail to break an arrhythmia. In this kind of a control study setting, this would have been the perfect time to have a separate arm evaluating if this has any benefit. Unfortunately, this was not done or even talked about in the paper

- In the end despite a differing patient population, this study does shed some light on utilizing alternative pad placements in hopes of increasing cardioversion efficacy. If a patient’s atrial fibrillation did not convert after ALE positioning and escalating doses of energy, it would not be unreasonable to attempt repeating the cardioversion and consider APE positioning, just always make sure the patient’s adequately sedated beforehand.

Figure 1: LifePak’s Truncated High-Peak Exponential Waveform

Figure 2: Zoll’s Rectilinear Waveform

Author’s Conclusions:

Anterior–lateral electrode positioning was more effective than anterior–posterior electrode positioning for biphasic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. There were no significant differences in any safety outcome.

Our Conclusion:

The patient population in this study are not those who we’ll be seeing in the emergency department, however this study does help add to our knowledge of pad positioning efficacy when converting atrial fibrillation. While there were many omitted considerations in the methodology of this study, it prompts the consideration of changing pad placement when escalation to maximum energy has already been attempted. When performing cardioversion for stable atrial fibrillation, consider utilizing the anterior-lateral pad positioning for higher first attempt success in obtaining normal sinus rhythm.

Clinical Bottom Line:

Although this multicenter, randomized, open-label, blinded-outcome trial had a very different patient population than those typically seen in the emergency department, strong consideration should be made in placing the pads in the anterior-lateral positioning during cardioversion. Doing so may very well reduce the number of shocks needed to convert stable atrial fibrillation patients to normal sinus rhythm.

REFERENCES:

- Schmidt AS, et al. Anterior-Lateral Versus Anterior-Posterior Electrode Position for Cardioverting Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2021 Dec 21. PMID: 34814700

- Botto GL, et al. External cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: role of paddle position on technical efficacy and energy requirements. Heart. Dec 1999; PMID: 10573502

- Kirchhof P, et al. Anterior-posterior versus anterior-lateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 Oct 2002; PMID: 12414201

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- First10inEM: What is the best pad position for cardioversion?

- REBEL EM: The BEST AF Trial – What is the Optimal Energy Selection for Cardioversion

- REBEL EM: Chemical vs Electrical Cardioversion in Acute Uncomplicated Atrial Fibrillation

- REBEL EM: AFib: Wait-and-See or Early Cardioversion to Obtain Normal Sinus Rhythm?

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim Rezaie, MD (Twitter: @Srrezaie)

The post EPIC Trial: Electrode Positioning in Cardioverting Atrial Fibrillation appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.