Background: Intubation and mechanical ventilation are commonly performed ED interventions and although patients optimally go to an ICU level of care afterwards, many of them remain in the ED for prolonged periods of time. It is widely accepted that the utilization of lung protective ventilation reduces ventilator-associated complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Additionally, it is believed that ventilatory-associated lung injury can occur early after the initiation of mechanical ventilation thus making ED management vital in preventing this disorder. Despite this, intubated ED patients are not optimally ventilated used lung-protective strategy on a routine basis.

Clinical Question: Can the adoption of an ED lung-protective ventilation protocol decrease the frequency of ventilator associated complications?

Article:

Fuller BM et al. Lung-Protective Ventilation Initiated in the Emergency Department (LOV-ED): A Quasi-Experimental, Before-After Trial. Ann Emerg Med 2017. PMID: 28259481

Population: All adult patients (> 18 years of age) who were mechanically ventilated through an ET tube in the Emergency Department.

Intervention: “After” period with initiation of a new lung-protective protocol (see figure below)

Control: “Before” period with routine ventilation strategies employed in the ED in question.

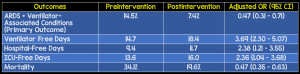

Outcomes:

- Primary: Composite of ARDS and ventilator associated conditions

- Secondary: Ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, hospital-free days and mortality

Design: Quasi-experimental before and after study. There was a 4.5 year “before/preintervention” period followed by a 6 month run-in period and a 1.5 year “after/intervention” period.

Excluded: Death or discontinuation of mechanical ventilation within 24 hours of presentation, long-term mechanical ventilation, the presence of a tracheostomy, transfer from another hospital, in ARDS during the ED presentation.

Primary Results:

-

1705 patients were included in the study

- Pre-intervention period: n = 1192

- Intervention period: n = 513

- Propensity score matched analysis was performed on 980 patients (490 in each group)

- After the run-in period, lung-protective ventilation increased by 48.4%

Critical Findings:

-

Secondary Outcomes all improved in intervention group

- Ventilator-free days: Incr 3.7 days (95% CI 2.3-5.1)

- ICU-free days: Incr 2.4 days (95% CI 1.0 – 3.7)

- Hospital-free days: Incr 2.4 days (95% CI 1.2-3.6)

- Mortality: Decr 14.5% (95% CI 0.35 – 0.63)

Strengths:

- Primary outcome clinically important

- Adjudicators of ARDS outcome blinded to all clinical information

- Propensity score matching performed to account for non-randomized nature of trial

- The intervention includes a simple, step-by-step protocol to implement a lung-protective strategy

- Treatment variables in the ED accounted for in the propensity score included intravenous fluids, administration of blood products, central venous catheter placement, antibiotics, and vasopressor use.

Limitations:

- Before and after design is susceptible to the effects of temporal trends in care that may lead to changes independent of this intervention

- The intervention bundle is multifaceted. It’s unclear if any of these pieces are more influential on outcomes than others

- Though propensity matching takes into account a number of cofounders, others may have been present that were not accounted for

- Patients during both periods may have been treated with either ventilation strategy. It is unclear from the data exact percentages treated with each approach. This may blunt or exaggerate the effect of the intervention

- A priori power calculation established 80% power to detect a 5-6% difference if 513 patients were collected. Only 490 patients were collected for the propensity matched analysis giving 80% power to detect a 6.7% difference (this was established after data collection completed)

- Ventilator settings were recorded twice daily in the ICU. Changes during the day may not have been captured by this system.

- It is unclear how long patients remained in the ED in either phase and how long the ventilator strategies were applied to the patients and if changes were made upon arrival in the ICU.

Lung Protective Strategy Protocol:

Discussion:

-

Lung-Protective Ventilation Strategy Implications:

- Starting lung-protective ventilation strategies in the ED is feasible

- Implementing lung-protective ventilation strategies in the ED influences ventilator practices in the ICU

- Implementing a lung-protective ventilation strategy in the ED is associated with a reduction in pulmonary complications, hospital mortality, and health care resource usage

Authors Conclusions:

“Implementing a mechanical ventilator protocol in the ED is feasible and is associated with significant improvements in the delivery of safe mechanical ventilation and clinical outcome.”

Our Conclusions:

We agree with the authors conclusions. This simple, inexpensive protocol to increase the use of a lung-protective ventilation strategy was associated with significant improvement in both the primary outcome as well as all secondary outcomes.

Potential to Impact Current Practice:

Although a prospective, randomized controlled trial would be useful in determining causality. In lieu of an RCT, this data should further encourage Emergency Providers to embrace lung-protective ventilation strategies for their intubated patients.

Clinical Bottom Line:

Patients intubated in the ED without reactive airway disease should be ventilated with a lung protect approach. Starting lung protective ventilation in the ED is feasible, it influences ventilator settings in the ICU and reduces pulmonary complications. Implementation includes getting an accurate height to use for the tidal volume, minimal FiO2 to meet an O2 saturation greater than 90%, matching PEEP to the FiO2 according to the ARDSNet protocol, keeping the plateau pressure < 30 mm Hg and keeping the head of the bed at 30 degrees.

References:

- Fuller BM et al. Lung-Protective Ventilation Initiated in the Emergency Department (LOV-ED): A Quasi-Experimental, Before-After Trial. Ann Emerg Med 2017. PMID: 28259481

For More on This Topic Checkout:

- Josh Farkas at Pulmcrit(EMCrit): MDCalc for the Perfect Tape-Measure Intubation

Post Peer Reviewed By: Salim Rezaie (Twitter: @srrezaie)

The post The Benefit of Lung Protective Ventilation in the ED Should be LOV-ED appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.