Background: Headache is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED) accounting for 2% of all visits [1]. Of the patients that present with headache,1 – 3% will be due to a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [1]. SAH is a true diagnostic dilemma as delays in diagnosis can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Further complicating matters, almost half of patients will be alert and neurologically intact at first presentation [3]. Non-Contrast Head CT (NCHCT) is very sensitive when performed soon after headache. However, we don’t want to order unnecessary NCHCTs as that increase cost and radiation exposure. Invasive testing such as lumbar puncture, which in itself can be a painful procedure, can also cause headache. The Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule was designed to help facilitate the identification of SAH in alert, neurologically intact adults presenting to the ED with acute, non-traumatic headache, while minimizing expensive and invasive over testing. This post will serve as a review of the current literature in the derivation and validation of the Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule.

Background: Headache is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED) accounting for 2% of all visits [1]. Of the patients that present with headache,1 – 3% will be due to a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [1]. SAH is a true diagnostic dilemma as delays in diagnosis can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Further complicating matters, almost half of patients will be alert and neurologically intact at first presentation [3]. Non-Contrast Head CT (NCHCT) is very sensitive when performed soon after headache. However, we don’t want to order unnecessary NCHCTs as that increase cost and radiation exposure. Invasive testing such as lumbar puncture, which in itself can be a painful procedure, can also cause headache. The Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule was designed to help facilitate the identification of SAH in alert, neurologically intact adults presenting to the ED with acute, non-traumatic headache, while minimizing expensive and invasive over testing. This post will serve as a review of the current literature in the derivation and validation of the Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule.

BMJ 2010 [1]

What They Did: This was a prospective, multicenter cohort study conducted at 6 hospitals in Canada trying to identify high risk clinical features for SAH in neurologically intact patients with headache

Outcomes:

- SAH was defined as:

- SAH blood on unenhanced head CT

- Xanthochromia in the CSF diagnosed by visual inspection

- RBCs (>5×106/L) in the final sample of CSF with an aneurysm or AVM evident on cerebral angiography

Inclusion:

- Alert patients (i.e. GCS 15)

- Age ≥16 years

- Presenting to an ED

- Non-traumatic headache (i.e. Absence of falls or direct trauma to the head in previous 7 days)

- Headache peaking within 1 hour or syncope associated with headache

- Headache onset ≤14days to presentation

Exclusion:

- ≥3 headaches of similar character and intensity in prior 6 months

- Confirmed diagnosis of SAH from other facilities

- Papilledema

- New focal neurological deficits

- Previous diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm or SAH

- Previous diagnosis of brain tumor

- Previous diagnosis of hydrocephalus

Results:

- 1999 patients enrolled

- 130 (6.5%) confirmed SAH

- 1657 (82.9%) of patients had a head CT, LP or both

- Head CT: 80.3%

- LP: 45.3%

- Both Head CT and LP: 42.7%

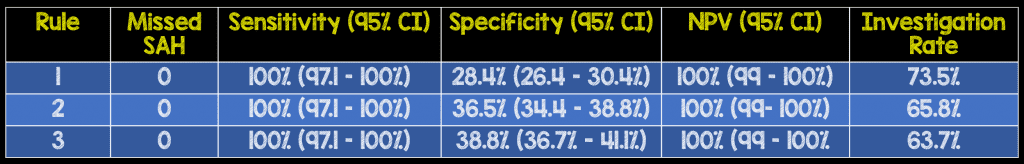

- 3 Rules Derived with 100% sensitivity for ruling out SAH

- Rule 1

- Age ≥40

- Complaint of neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed LOC

- Onset with exertion

-

Rule 2

- Arrival by ambulance

- Age ≥45

- Vomiting at least once

- DBP ≥100mmHg

-

Rule 3

- Arrival by ambulance

- SBP ≥160mmHg

- Complaint of neck pain or stiffness

- Age 45 – 55

- Per the authors, investigation rate for all three rules was lower than the baseline rate of investigation (82.9%) in this study

Strengths:

- Followed previously established methodological standards for developing and testing clinical decision rules

- The definition of SAH was clearly defined (The definition of SAH was created a priori by a consensus of 5 EM physicians and 1 neurosurgeon)

- Predictor variables were prospectively evaluated and documented on standardized data collection forms before head CT or LP

- Large sample size allowed for narrow confidence intervals for sensitivity (Took local incidence to make calculations and enrolled appropriate number of patients to obtain tight CIs)

- Derived rules only contained 4 variables which are all simple and well defined allowing for easy incorporation into everyday practice

- Several rules were derived for future validation due to the high morbidity and mortality associated with missed diagnosis

- Interobserver reliability was assessed by having a second physician also complete a data collection form without knowledge of the 1stphysicians findings

- Reading radiologists were blinded to contents of data collection forms when interpreting scans

- Robust follow up for patients (i.e. at least 5 phone calls, additional review of health records, and review of coroner’s office records)

- Used recursive partitioning analysis over logistic regression analysis to increase sensitivity of variables as this was more important than overall accuracy

- Only 26 patients (1.3%) of the total study population were lost to follow up

Limitations:

- All physicians had a formal 1hr teaching presentation on the use of the Ottawa SAH Decision rule, which may limit generalizability at all institutions

- All CT findings were verified by local attending radiologists. This may not be feasible in centers that have resident radiologists reading CT scans

- 1050 missed eligible patients but the demographics were similar to patients enrolled in the study, and there were no cases of SAH on 1 month (87.5% of patients) and 6 month (80.6%) of patients that were followed up

- Decision rules still need to be validated before incorporation into clinical practice

Discussion:

- Authors suggest that patients with headache that peaks within 1 hour, severe at onset, and different from prior with any of the following should be considered for evaluation for SAH:

- Age ≥40

- Witnessed LOC

- Complaint of neck pain or stiffness

- Onset with exertion

- Arrival by ambulance

- Vomiting

- DBP ≥100mmHg

- SBP ≥160mmHg

Author Conclusion: “Clinical characteristics can be predictive for subarachnoid haemorrhage. Practical and sensitive clinical decision rules can be used in patients with a headache peaking within an hour. Further study of these proposed decision rules, including prospective validation, could allow clinicians to be more selective and accurate when investigating patients with headache.”

JAMA 2013 [2]

What They Did: Prospective, multicenter cohort follow up study at 10 Canadian EDs assessing the accuracy, reliability, acceptability, and potential refinement of the prior 3 clinical decision rules created in the BMJ 2010 [1] publication

Outcomes:

- SAH defined as any one of the following:

- Subarachnoid blood on CT scan

- Xanthochromia in CSF

- RBCs (>1 x106/L) in final tube of CSF fluid + positive angiography findings

Inclusion:

- Age ≥16 years

- Nontraumatic headache

- Headache reaching maximal intensity within 1 hour

- GCS of 15

- No fall or direct head trauma in previous 7 days

- Presentation ≤14 days from headache onset

Exclusion:

- 3 or more headaches of same character and intensity over a period of 6 months

- Referred from another facility with confirmed SAH

- Returned for reassessment of the same headache if already investigated with both CT and LP

- Papilledema

- New focal neurologic deficits

- Previous diagnosis of cerebral aneurysm, SAH, brain neoplasm, or hydrocephalus

Results:

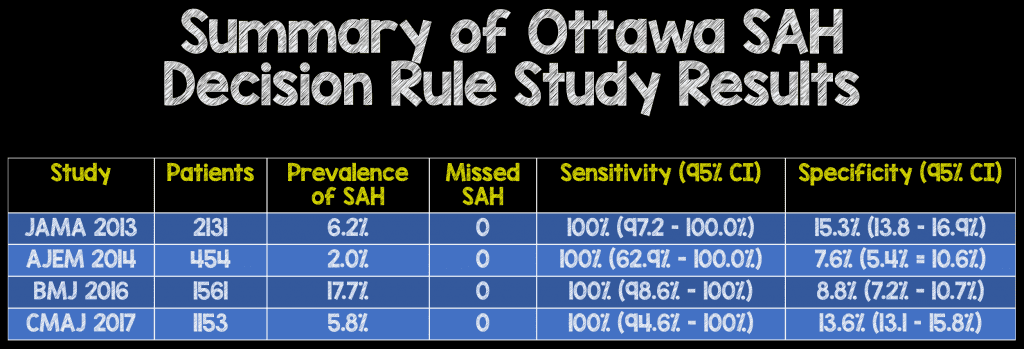

- 2131 enrolled patients

- 132 (6.2%) had SAH

- The rules were then refined and Rule 1 was found to be the best model with the addition of “thunderclap headache” (defined as instantly peaking pain) and limited neck flexion on examination (defined as inability to touch chin to chest or raise head 3cm off the bed if supine)

- This resulted in a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 97.2 – 100.0%, Specificity of 15.3% (95% CI 13.8 – 16.9%).

- This refined rule was designated the Ottawa SAH decision Rule:

- For alert patients >16 years with new severe nontraumatic headache reaching maximum intensity within 1hr

- NOT for patients with new neurologic deficits, previous aneurysms, SAH, brain tumors, or history of recurrent headaches (≥3 episodes over the course of ≥6months)

-

Investigate if ≥1 high-risk variable present (Final Ottawa SAH Decision Rule):

- Age≥40y

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed LOC

- Onset during exertion

- Thunderclap headache (instantly peaking pain)

- Limited neck flexion on exam

Strengths:

- Physicians recorded clinical findings on data forms prior to head CT and LP

- Interobserver agreement was evaluated on “some patients” to ensure reliability of the clinical decision rule

- As all patients did not undergo head CT and LP, a proxy outcome assessment tool was used for 1 month and 6month telephone interview follow ups to identify patients who developed a subsequent SAH

- Once again a power calculation was performed to find the ideal patient population to size to achieve a 100% sensitivity with 95% CI of 97 – 100%

Limitations:

- All physicians had a 1 hour formal orientation on how to use the Ottawa SAH Decision rule, which again may limit its application in centers where this is not done (i.e. physicians may not apply the rule correctly)

- Inclusion of patients with non-thunderclap headaches (i.e. up to 1 hr from onset to peak intensity) may have diluted the acuity of patients

- The Ottawa SAH Decision Rule has not been validated at this point in a population outside of Canada. As with any decision rule, external validation is important to ensure patient safety and generalizability

- This study actually derives a new instrument since it’s adding to the prior study, so technically, still a derivation study, although it is called a refinement study

- Unclear how many patients the inter-observer reliability was performed in

- To obtain high sensitivity, specificity suffers

Discussion:

- Ottawa SAH Decision Rule does not reduce testing (CT, LP) vs current practice but does help to standardize which patients with acute headache may require investigations

Author Conclusion: “Among patients presenting to the emergency department with acute nontraumatic headache that reached maximal intensity within 1 hour and who had normal neurologic examination findings, the Ottawa SAH Rule was highly sensitive for identifying subarachnoid hemorrhage. The findings apply only to patients with these specific clinical characteristics and require additional evaluation in implementation studies before the rule is applied in routine clinical care.”

CMAJ 2017 [3]

What They Did: This was a multicenter prospective cohort study at 6 Canadian EDs validating the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule

Outcomes:

- SAH is defined as any of the following:

- Subarachnoid blood visible on head CT

- Xanthochromia in the CSF (by visual inspection)

- Presence of RBCs (>1 x 106/L) in the final tube of the CSF with an aneurysm or AVM visible on CTA

Inclusion: Alert, neurologically intact adult (≥16 years) patients with a headache peaking within 1 hour of onset

Exclusion:

- GCS <15

- Direct head trauma in the previous 7 days

- ≥14 days after onset of headache

- History of 3 or more recurrent headaches of the same character and intensity as the presenting headache over a period of ≥6months

- Referred from another facility with confirmed SAH

- Returned for reassessment of same headache after already having had both CT and LP

- Papilledema on fundoscopic exam

- New focal neurologic deficit

- Prior history of cerebral aneurysm, SAH, brain neoplasm, VP shunt, or hydrocephalus

Results:

- 1153 patients enrolled (Only lost 8 patients to follow up)

- 67 had SAH (5.8%)

- Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

- Sensitivity: 100% (95% CI 94.6% – 100%)

- Specificity 13.6% (95% CI 13.1% – 15.8%)

- PLR: 1.16

- NLR: 0

Strengths:

- This is the first true validation study, although it is still not an external validation study

- Asks a clinically important question about a diagnosis that is difficult to make

- Physicians scored the Ottawa Subarachnoid Decision rule prior to investigations were started

Limitations:

- Each hospital had previously participated in the derivation phase of the study meaning they had comfort with application of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule, which may not be the case at other centers. Using the same sites does not bias rule performance, but it may overestimate the ability of physicians to use the rule correctly

- 1 in 3 potentially eligible patients were missed and not enrolled in this study

- Validation of the clinical decision rule in a system outside Canada is still needed before full implementation and generalizability to clinical practice

- CI for sensitivity sider than the group initially set out to establish and wider than we would like to see

- The overall weakness with this study and previous studies is that the gold standard of, head CT + LP, isn’t widely considered the gold standard. However this is made up for in the follow up with only 8 patients being lost to follow up, meaning >99% follow up rate

Discussion:

- Pooling patients from the JAMA 2013 publication [2] with this study a total of 3874 patients (2131 from JAMA 2013 + 1743 Eligible from CMAJ 2017) would have been prospectively assessed. More impressively the Ottawa SAH Decision rule had a:

- Sensitivity 100% (95% CI 98.4 – 100%)

- Specificity 15.9% (95% CI 14.8 – 17.1%)

Author Conclusion: “We found that the Ottawa SAH Rule was sensitive for identifying subarachnoid hemorrhage in otherwise alert and neurologically intact patients. We believe that the Ottawa SAH Rule can be used to rule out this serious diagnosis, thereby decreasing the number of cases missed while constraining rates of neuroimaging.”

All 3 of the above studies were done by the same group of authors and within the same Canadian system of hospitals, but are there any external validation studies to support the incorporation of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule into everyday clinical practice?

AJEM 2014 [4]

What They Did: This was a health records review of consecutive patients presenting with headache at a single center in an attempt to externally validate the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

Outcomes: External validation of the performance of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

Inclusion:

- Patients >15 years of age

- Nontraumatic headache

- Headache that was sudden in onset, reaching maximal intensity within 1 hour

Exclusion:

- Head trauma within 7 days

- New neurologic deficits

- Any prior history of cerebral aneurysm, SAH, hydrocephalus, cerebral neoplasm

- Established recurrent headache syndromes

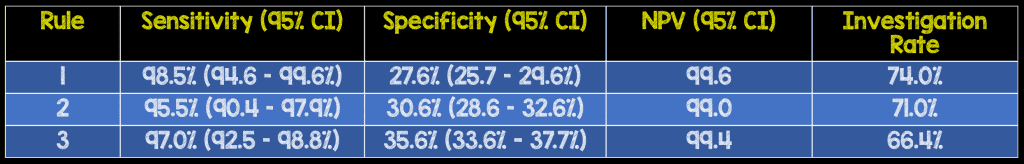

Results:

- 454 patients (9.0%) met eligibility out of 5034 ED visits with acute headache

- 9 cases of SAH (2.0%)

- Ottawa SAH Decision Rule Performance:

- Sensitivity: 100% (95% CI 62.9% – 100%)

- Specificity 7.6% (95% CI 5.4% – 10.6%)

- NPV: 100% (95% CI 87.4% – 100%)

Strengths:

- First external validation study of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

- Consecutive patients were reviewed minimizing risk of selection bias

- Abstractors met periodically with primary investigator to review any questions that arose in data abstraction and to resolve disagreements between abstractors

- The social security death index database was reviewed for patients who did not have subsequent ED visits documented in the electronic medical record

Limitations:

- This was a retrospective, chart review; not a prospective study of patients. Documentation of the onset and duration of headache may not be completely accurate.In this study, 310 patients were excluded due to lack of documentation of time of maximal intensity of headache.

- The prevalence of SAH in this study was quite low (i.e. 2.0%) compared to the Perry studies [1][2][3], which could have an effect on the high sensitivity in this study.

- Records were only followed out for 7 days after original visit, therefore no long term outcomes assessed

- Abstractors were not blinded to the study objectives and hypothesis potentially causing bias in data gathering

- Small patient population led to a wide 95% CI in regards to sensitivity (i.e. 62.9% – 100.0%)

Discussion:

- In this study application of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule would have increased investigation by 16% compared to baseline practices. Application of the decision rule in this practice setting would have increased healthcare utilization without improving patient safety.

- Pooling data from this study with the two Perry trials [2][3] a total of 4,328 patients the Ottawa SAH Decision rule still held true to its 100% sensitivity.

Author Conclusion: “The OSAH rule was 100% sensitive in the eligible cohort. However, its low specificity and applicability to only a minority of patients with headache (9%) reduce its potential impact on practice.”

EuJEM 2017 [5]

What They Did: This was a retrospective study of prospectively collected data from 34 EDs in Queensland, Australia trying todetermine the proportion of ED patients with any headache fulfilling the entry criteria for the Ottawa SAH rul

Outcomes:The proportion of patients who fulfilled entry criteria for the Ottawa SAH decision rule and the proportion fulfilling any criteria for further work-up

Inclusion:

- Older than 18 years of age

- Nontraumatic headache of any potential cause

Exclusion:

- Any headache caused by trauma, falls or other injury patterns

Results:

- 847 patients with headache presentations were identified over 4 weeks

- 18 patients (2.1%) had a final diagnosis of SAH

- Data was available for 644 patients

- 149 patients (23.1%) fulfilled entry criteria

- 30 patients (<5%) that fulfilled entry criteria did not have any high-risk variables for SAH

- 0 SAH were missed

Strengths:

- Information was abstracted from a state-wide hospital database >3 months after the index presentation

Limitations:

- The diagnosis of SAH was made on the basis of final hospital discharge diagnosis and not based on a set definition of SAH

- Retrospective study, meaning not all data is collected (Only what is in the chart) and also the reliability of collected may be flawed

- Small percentage of headache patients eligible in this study

- Age is >18 years instead of >15years which further limits the patients being eligible

- SAH rate is significantly lower in this population than it is in previous Perry studies

Discussion:

- Pooling all the trials available, 4,477 patients with headache presentations having the Ottawa SAH Decision rule applied maintained its 100% sensitivity, but the final two studies [4][5] showed a low eligibility criteria of 9 – 23.1% of all headache presentations.

- A second issue brought up in this study is that of the patients who were eligible for the application of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule <5% of them did not have any high risk features, meaning that >95% would require further workup (i.e. CT head and/or LP) to rule out SAH.

Author Conclusion: “In this descriptive observational study, the majority of ED patients presenting with a headache did not fulfill the entry criteria for the Ottawa SAH rule. Less than 5% of the patients in this cohort could have SAH excluded on the basis of the rule. More definitive studies are needed to determine an accepted benchmark for the proportion of patient receiving further work-up (computed tomographic brain) after fulfilling the entry criteria for the Ottawa SAH rule.”

BMJ 2016 [6]

What they did: Multicenter prospective observational cohort study in 5 hospitals in Japan

Outcomes: Definitive diagnosis of SAH based on head CT or LP findings (non-traumatic RBCs in the final tube of CSF or xanthochromia) and CT angiography to confirm whether an underlying pathology caused the SAH

Inclusion:

- Age >15 years

- Acute headache

- Presentation within 14 days of onset of headache

Exclusion:

- Trauma or toxic (drugs or alcohol) causes

- Unconscious state

- Recurrent headache syndromes (history of ≥3 recurrences of headache with the same characteristics and intensity as the presenting headache over a period of >6months)

Results:

- 1781 patients eligible

- 1561 patients enrolled

- 277 patients had SAH (17.7%)

- 1371 patients had blood work

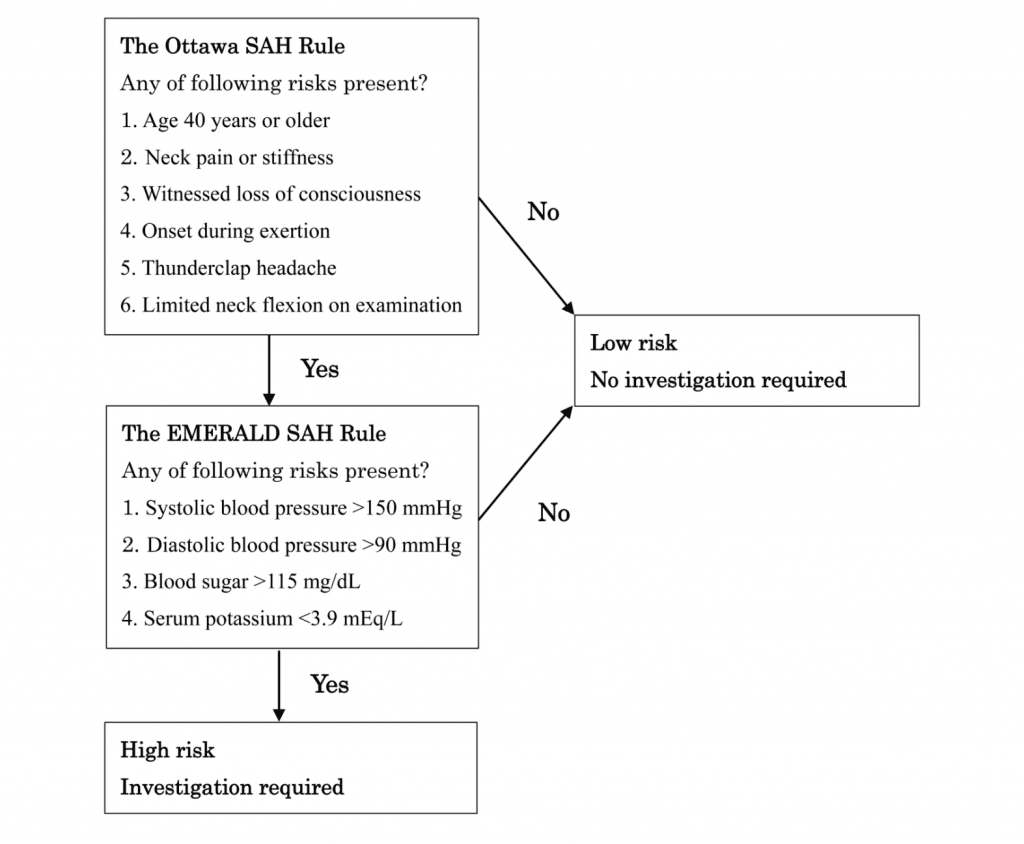

- A new rule (The EMERALD SAH Rule) was derived:

- Step 1 – application of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

- Step 2 – If not ruled out by the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule any of the following were deemed high risk:

- SBP >150mmHg

- DPB > 90mmHg

- Blood sugar > 115mg/dL

- Serum potassium <3.9mEq/L

- Sensitivity: 100% (95% CI 98.6% – 100%)

- Specificity 14.5% (95% CI 12.5% – 16.9%)

- PLR: 1.2

- NLR: 0

- Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

- Sensitivity: 100% (95% CI 98.6% – 100%)

- Specificity: 8.8% (7.2% – 10.7%)

Strengths:

- The EMERALD SAH Rule used objective values to exclude SAH, limiting interobserver variability

- Followed previously established methodological standards in developing the new clinical decision rule

- Patients with new neurological deficits or history of aneurysm or brain tumor were not excluded in this study due to the common practice of non-enhanced CT followed by enhanced CT and routine blood testing

Weaknesses:

- This study had a higher positive SAH rate (17.7%) than the Ottawa SAH Rule cohort. This may have been due to the referral base from smaller hospitals or clinics

- The LP rate was very low in this study (2.6%). This may have been due to the fifth generation or later imaging done by MDCT which detect SAH with a sensitivity approaching 100%. Also the standard care in Japan is to perform non-contrast head CT followed by CT angiography instead of LP due to the invasiveness of the procedure

- Interobserver agreement was not measured for the Ottawa-like rule carried out in this study

- The time to peak headache intensity was not recorded for all patients

- The EMARALD SAH Rule still needs to be properly validated before incorporation into clinical practice

Discussion:

- The 2-Step Decision-Making Rule to Rule Out SAH for Adult Patients

Author Conclusion: “While maintaining equal sensitivity, our new rule seemed to offer higher specificity than the previous rules proposed by the Ottawa group. Despite the need for blood sampling, this method can reduce unnecessary head CT in patients with acute headache.”

Summary of Sensitivity and Specificity of the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule

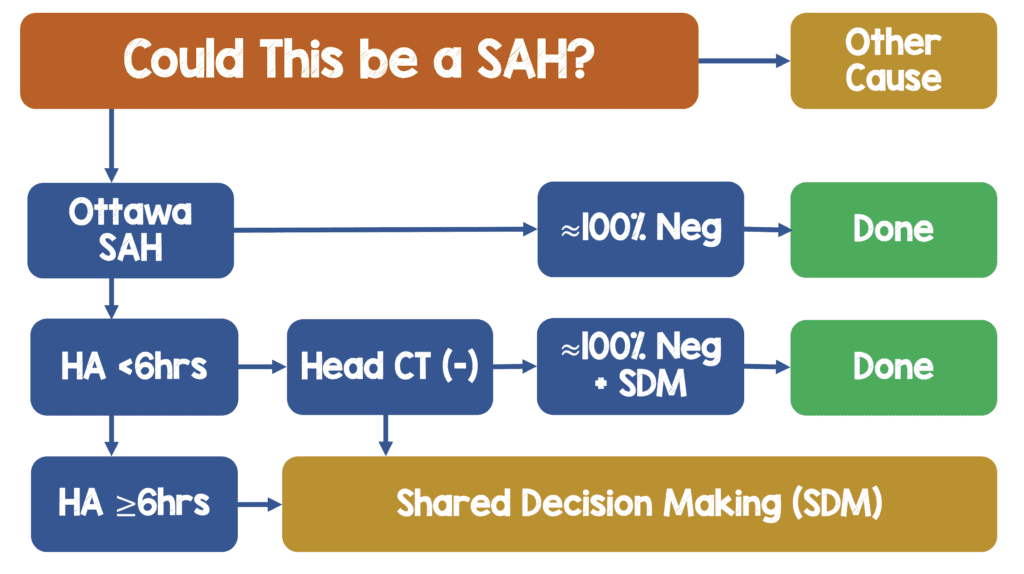

Workflow of SAH (I am Not Currently Using Ottawa SAH Decision Rule, But if I was, this is how I would use it)

Clinical Take Home Point:

- The Ottawa SAH Decision Rule is defined as any of the following as a high-risk patient requiring further workup:

- Age≥40y

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed LOC

- Onset during exertion

- Thunderclap headache (instantly peaking pain)

- Limited neck flexion on exam

- To date the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule holds a 100% sensitivity for ruling out SAH, in >5,000 adult patients, from 4 countries, who are alert, neurologically intact (GCS 15) presenting to the ED with acute non-traumatic headache. It is important to remember that most studies confidence intervals went down to 98% and one small study went as low as 63%, so take the 100% sensitivity with a grain of salt

- Subsequent studies have shown the Ottawa SAH Decision Rule has limited application to a small proportion of patients presenting with acute headache (5 – 25%) which may limit its adoption in general practice.

- Some of the factors in the Ottawa SAH Decision rule are subjective (i.e. headache during exertion, neck pain or stiffness) which may decrease interobserver reliability in other environments

- The specificity of the Ottawa SAH Decision rule (7.6% – 15.3%) is also poor which can lead to more patients needing further workup (head CT and/or LP) who have one or more high risk features. This is a 1-way decision instrument. In other words, a positive decision rule risk factor does NOT mean you would have to pursue SAH. Clinical judgement must be used in determining which patients will require further workup as blanket workups will lead to increased health costs, and potential harm (radiation and invasive procedures) to patients.

References:

- Perry JJ et al. High Risk Clinical Characteristics for Subarachnoid Haemorrhage in Patients with Acute Headache: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2010. PMID: 21030443

- Perry JJ et al. Clinical Decision Rules ot Rule Out Subarachnoid Hemorrhage for Acute Headache. JAMA 2013. PMID: 24065011

- Perry JJ et al. Validation of the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule in Patients with Acute Headache. CMAJ 2017. PMID: 29133539

- Bellolio MF et al. External Validation of the Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Clinical Decision rule in Patients with Acute Headache. AJEM 2014. PMID: 25511365

- Chu KH et al. Applying the Ottawa Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Rule on a cohort of emergency Department Patients with Headache. EuJEM 2017. PMID: 29215380

- Kumura A et al. New Clinical Decision rule to Exclude Subarachnoid Haemorrhae for Acute Headache: A Prospective Multicentre Observational Study BMJ 2016. PMID: 27612533

- Ramachandran S et al. Can the Ottawa Subarachnoid Haemorrhage Rule Help Reduce Investigation Rates for Suspected Subarachnoid Haemorrhage? AJEM 2018 PMID: 29776829

For More Thoughts on This Topic Checkout:

- Natalie May at St. Emlyn’s: JC – Subarachnoid Haemorrhage, Decision Rules, & Overtesting Headaches

- Anand Swaminathan at CORE EM: The Ottawa SAH Decision Instrument

- Ken Milne at The SGEM: SGEM #201 – It’s in the Way That You Use It – Ottawa SAH Tool

Post Peer Reviewed By: Anand Swaminathan, MD (Twitter: @EMSwami)

The post The Ottawa SAH Clinical Decision Rule appeared first on REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog.